More on:

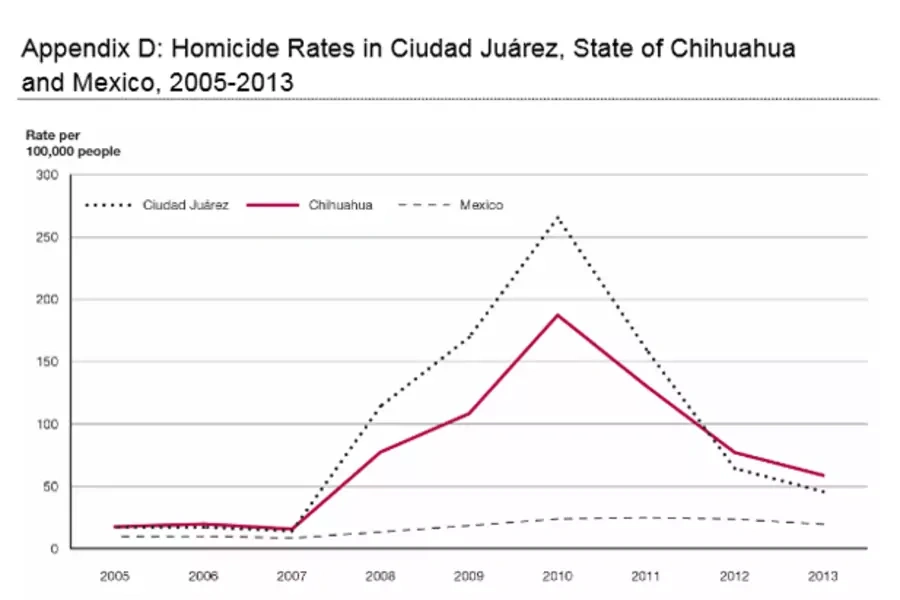

In 2010, the homicide rate in Mexico’s Ciudad Juarez rose to over 250 per 100,000 inhabitants making it the most dangerous city in the world. Other crimes—extortions, kidnappings, and carjackings—also increased dramatically. By 2014, these rates had plummeted. The 424 reported murders still outpaced 2006 figures, but were just 14 percent of the 3,084 murders four years earlier.

Last month, CFR hosted Javier Ciurlizza, program director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the International Crisis Group (ICG), Jorge Contreras, founder and coordinator of the Fideicomiso para la Competitividad y Seguridad Ciudadana, and Alejandra de la Vega, coordinator of the Mesa de Seguridad y Justicia de Ciudad Juarez, to discuss Ciudad Juarez’s recovery and potential future.

According to a February 2015 ICG report, violence escalated due to three factors. First, drug cartels militarized as the value of and competition for plazas increased, and law enforcement efforts quickly followed suit. U.S. policy changes—the elimination of the ban on assault rifles, greater deportations of ex-convicts, increased border patrol—as well as a spike in cocaine prices, also played a role. Lastly, the 2008 financial crisis led to a loss of some 90,000 maquiladora jobs, providing the cartels and their gangs with easy recruits.

In response, many Ciudad Juarez residents and civil society groups rallied together. They created hotlines to report kidnappings, tracked crime to share with and prod the police into action, and reached out to officials at all levels of government, finding and working with reformers while demanding the removal of the corrupted.

In the wake of the 2010 Villas de Salvarcar massacre of fifteen people, the federal government turned its attention and resources to Ciudad Juarez. The federal Todos Somos Juarez initiative brought some $400 million to the city, mostly for health, education, and economic development programs.

On security, the national government worked closely with state and local counterparts, as well as with citizens and civic groups through a Mesa de Seguridad y Justicia, developing strategies to cut crime. The business community also endorsed a surcharge of 5 percent of their payroll taxes to fund citizen led safety efforts, including collecting independent crime data. Combined with an economic recovery and what many analysts depict as the Sinaloa cartel triumph over its rivals, violence declined dramatically.

The discussion ended focusing on whether Ciudad Juarez provides lessons for other cities struggling with insecurity. Some aspects—the long history of civic engagement, the huge influx of federal resources—are hard to replicate. But others, including Mesas bringing together the government, private sector, and civil society leaders, could perhaps gain traction. And International Crisis Group comparisons also show that there isn’t just one path—Medellin, Colombia’s recovery came from top-down state led interventions and investment in transportation, infrastructure, and public spaces. As Mexico struggles to reduce violence in Acapulco, Morelia, Reynosa, and other cities, the federal government would do well to try to understand and then emulate the lessons of Ciudad Juarez.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store