TWE Remembers: The Fulbright Program

Sunday marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of the creation of the Fulbright International Exchange Program. Last December I flagged the date as one of ten anniversaries to note in 2021. So I asked my summer intern, Leila Marhamati, to explore the program’s history. Here is what she found.

Sometimes big things come from halting starts.

More on:

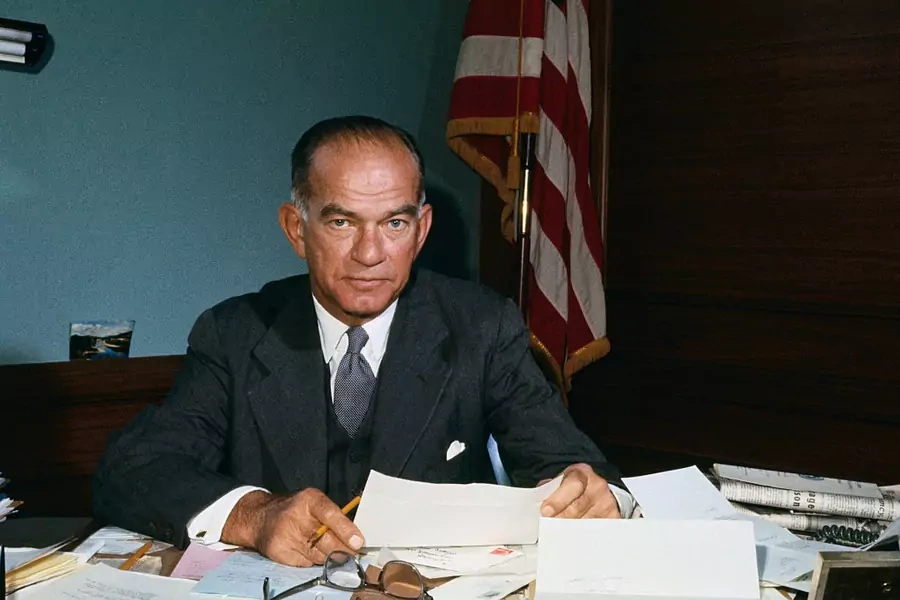

In 1945, J. William Fulbright (D-AK) was serving his first term in the U.S. Senate as the United States and the rest of the world emerged from the horrors of World War II. Fostering a sound foreign policy for the postwar world—one founded on cooperation among nations—quickly became his passion. He was convinced that education and diplomacy would be invaluable tools for creating that foreign policy. A month after the war ended, he submitted a bill to establish a program designed to produce open-minded scholars willing “to cooperate in constructive activities rather than compete in a mindless contest of mutual destruction,” eventual policymakers who would maintain peace in the world. Seventy-five years ago today his vision became a reality when President Harry Truman signed the Fulbright Program into law.

Fulbright’s bill amended the Surplus Property Act of 1944, under which excess U.S. war properties were sold abroad. His idea was to use the revenues from those sales to fund educational exchange between the U.S. and participating countries. U.S. scholars, students, and teachers would be eligible to travel abroad to participating countries and foreign scholars would be able to study in the United States.

On November 10, 1947, China became the first country to sign a Fulbright agreement with the United States. Burma (now Myanmar) followed shortly thereafter. These agreements took over a year to conclude because of problems with various U.S. Cabinet departments and arguments that the funds from the sale of surplus property should instead be used to build embassies. But Secretary of State Dean Acheson, as passionate about the program as Fulbright, was determined to fulfill the senator’s vision. He told U.S. diplomats that they should “devote all the resources” at your command to the speediest possible initiation of operations." With the supplementation of private funds, the State Department was able to reallocate enough money to get the program off the ground. The passage of the U.S. Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 gave the Fulbright Program further impetus. It authorized the State Department to ask Congress to appropriate funds for educational exchange outside of war properties, increasing the number of countries that could participate. Within five years of the Fulbright Program's establishment, more than twenty countries had signed agreements with the United States.

The fact that the Fulbright Program was authorized by the Surplus Property Act gave rise to one of its unique features: its binationalism. Because foreign governments had to agree on the rates at which war properties were sold, they became involved in the program’s administration. Eager to avoid appearing to impose its ideals onto other nations, though that was one of Fulbright’s intentions, the United States took measures to emphasize the academic legitimacy of the program. The Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board (FFSB) was created in 1947 to decide which students and international institutions were qualified to participate. To insulate the scholarships from politics, members of the FFSB are presidentially-appointed and chosen from private rather than public life. Once a country signs a Fulbright agreement with the United States, a binational commission is created to decide how the program will operate in the host country.

You might think the Fulbright Program favors scholars from traditional academic disciplines like English or economics. But the program has sought since its creation to recruit talented individuals from all disciplines, and not just from university campuses. In 1968, for example, Ronald Radford received a Fulbright arts grant to study flamenco guitar with Spanish masters Diego del Gastor and Paco de Lucia. Eleanor King, the director of the dance program at the University of Arkansas from 1952 to 1972, received two Fulbright scholarships in the 1960s to research dance in Japan. Playwright Edward Albee, author John Updike, soprano Renee Fleming, and actor John Lithgow have all have been awarded Fulbrights.

More on:

But even as the Fulbright Program championed peace and open-mindedness, Senator Fulbright didn’t always practice those ideals at home. Throughout his decades on Capitol Hill, which saw him rise to become the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he consistently voted in support of racial segregation in education and against civil rights legislation. His hypocrisy, which the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs that sponsors the program now recognizes, is obvious and upsetting. And, for all his support of the creation of the FFSB, Fulbright originally wanted Americans abroad to engage in a form of cultural imperialism, spreading American ideals while remaining immune to those of foreign countries. Instead of promoting understanding and toleration, then, his idea of peace between nations rested more on cultural domination.

In its seventy-five years, the Fulbright Program has become the foremost international exchange program, reaching over 160 countries on six continents. Each year, about 2,000 U.S. students and 800 U.S. scholars receive Fulbright awards, as do 4,000 foreign students and 900 foreign scholars. Sixty Fulbright alumni have gone on to win Nobel Prizes, seventy-five have become MacArthur Foundation Fellows, eighty-nine have won Pulitzer Prizes, and thirty-nine have become heads of state.

The program’s prestige and success haven’t made it impervious to criticism, though. In the 1950s, Senator Joe McCarthy denounced it for importing communism into the United States. Three decades later, President Ronald Reagan tried, unsuccessfully, to cut the program’s budget in half. And it’s not just Republicans who have sought to pare back the Fulbright Program—Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama both sought budget cuts. Most recently, President Donald Trump called for slashing the Fulbright budget by 71 percent. Congress ignored that request, as it had similar calls in the past. It instead increased the budget by $800,000 in the 2020-21 fiscal year. Both Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill see the Fulbright Program highlighting the best of American values and promoting American interests abroad.

It’s likely that none of the people involved in the creation of the Fulbright Program foresaw how successful it would become. And initially it looked as if bureaucratic politics and competing priorities would push it into the ash heap of failed policy initiatives. But after its faltering start, the Fulbright Program blossomed into one of the great policy successes of the early Cold War and one of the great tools of U.S. soft power. The evidence is in the program’s reach: six continents, 160+ countries, and 400,000 scholars.

Margaret Gach assisted in the preparation of this post.

Online Store

Online Store