International Sanctions on Iran

Updated

U.S. and international sanctions have battered the Iranian economy and brought Tehran to negotiate over its nuclear program. Lifting them is central to a deal but will be a complex process.

- Since 2005, EU, UN, and U.S. sanctions have targeted Iran for violating treaties under which it promised not to pursue nuclear weapons.

- These sanctions have caused unemployment and inflation rates to skyrocket, devastating Iran’s economy.

Introduction

The United States, the United Nations, and the European Union have levied multiple sanctions on Iran for its nuclear program since the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA), the UN’s nuclear watchdog, found in September 2005 that Tehran was not compliant [PDF] with its international obligations. The United States spearheaded international efforts to financially isolate Tehran and block its oil exports to raise the cost of Iran’s efforts to develop a potential nuclear-weapons capability and to bring its government to the negotiating table.

Iran agreed to restrictions on its nuclear program and intensive inspections in an agreement signed with world powers in July 2015. Under the deal, many of the most punishing sanctions are poised to be lifted when the IAEA verifies that Iran has taken steps such as reducing its stockpiles of fissile materials and centrifuges. Still, some sanctions are unrelated to nuclear proliferation and will remain in place.

Why does Iran face sanctions?

Iran faces international sanctions for a clandestine nuclear program that the IAEA and major powers say violate its treaty obligations. When Iran acceded to the Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1967, it promised to never become a nuclear-armed state. But over the course of the 1970s, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s policies raised U.S. concerns that Iran had nuclear-weapons ambitions. In 1974 Iran signed the IAEA Safeguards Agreement, a supplement to the NPT in which it consented to inspections.

The Iranian Revolution in 1979 ushered in a clerical regime, and international concerns that Iran was pursuing a nuclear weapon resurfaced the following decade as the Islamic Republic fought a grinding, eight-year war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which had a nuclear program of its own. These suspicions continued into the mid-1990s, when President Bill Clinton’s administration levied sanctions on foreign firms believed to be enabling a nuclear-arms program.

In the early 2000s, indications of work on uranium enrichment renewed international concerns, spurring several rounds of sanctions from the United Nations, the EU, and the U.S. government. These international sanctions have sought to block Iran’s access to nuclear-related materials and put an economic vise on the Iranian government to compel it to end its uranium-enrichment program and other nuclear-weapons-related efforts.

U.S. sanctions on Iran, however, long predate these nuclear nonproliferation concerns. The United States first levied economic and political sanctions against Iran during the 1979–81 hostage crisis, shortly after Iran’s Islamic Revolution. On November 14, 1979, President Jimmy Carter froze all Iranian assets “which are or become subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.” The United States imposed additional sanctions when, in January 1984, the Lebanon-based militant group Hezbollah, an Iranian client, was implicated in the bombing of the U.S. Marine base in Beirut. That year, the United States designated Iran a state sponsor of terrorism. The designation, which remains in place, triggers a host of sanctions, including restrictions on U.S. foreign assistance, a ban on arms transfers, and export controls for dual-use items. Sanctions related to sponsorship of terrorism and human rights abuses were not affected by the nuclear deal.

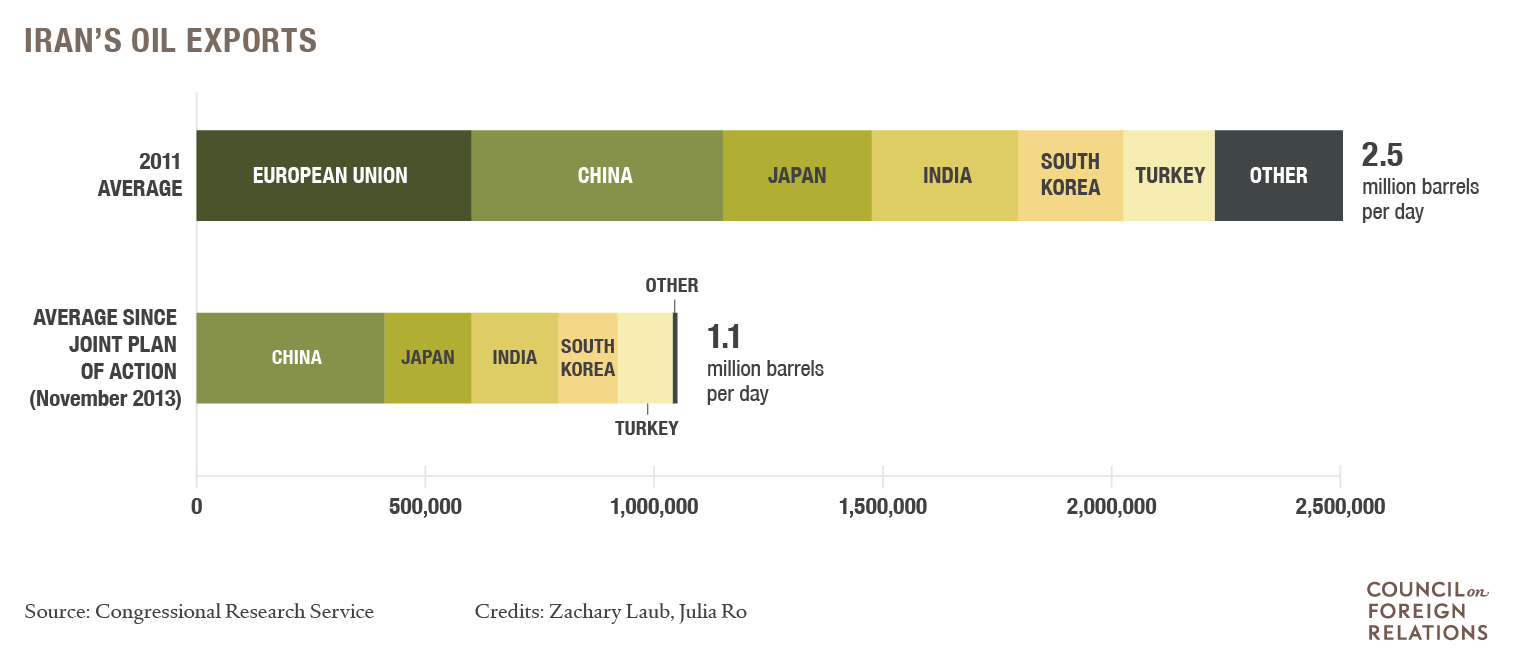

In November 2013, Iran and the P5+1 signed an interim agreement known as the Joint Plan of Action (JPA) that provided some sanctions relief and access to $4.2 billion in previously frozen assets in exchange for limiting uranium enrichment and permitting international inspectors to access sensitive sites. The JPA capped Iran’s crude oil exports at 1.1 million barrels per day, less than half its 2011 export level. Washington and Brussels will keep the terms of the JPA in effect until the IAEA has verified that Iran has followed through on an agreed-upon set of steps to limit its nuclear program, which will likely come several months after the July 14 agreement. The U.S. Treasury Department notes that no other relief has come into effect, and the extant nuclear sanctions will continue to be enforced until the IAEA verifies Iran’s compliance on what would be known, in the agreement’s parlance, as “implementation day.”

What are the U.S. sanctions?

U.S. sanctions cover a variety of purposes related to the country’s internal and external affairs, ranging from weapons proliferation to human rights abuses within Iran to state sponsorship of terrorism and fomenting instability abroad. They target broad sectors as well as specific individuals and entities, both Iranian nationals and nonnationals who have dealings with sanctioned Iranians.

- Financial/banking: U.S. sanctions administered by the Treasury Department have sought to isolate Iran from the international financial system. Beyond a prohibition on U.S.-based institutions having financial dealings with Iran, Treasury enforces extraterritorial, or secondary, sanctions: Under the 2011 Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act (CISADA), foreign-based financial institutions or subsidiaries that deal with sanctioned banks are barred from conducting deals in the United States or with the U.S. dollar, which then-Treasury Under Secretary David Cohen called “a death penalty for any international bank” [PDF]. At the end of 2011, the United States moved to prevent importers of Iranian oil from making payments through Iran’s central bank, though it exempted a handful of countries that had made a “significant reduction” in their purchases. Other measures restrict Iran’s access to foreign currencies so that funds from oil importers can only be used for bilateral trade with the purchasing country or to access humanitarian goods.

- Oil exports: Along with pressure on Iran’s access to international financial systems, curtailing oil revenue has been the principal focus of the Obama administration as it stepped up pressure on nuclear nonproliferation. Prior to 2012, oil exports provided half the Iranian government’s revenue and made up one-fifth of the country’s GDP; its exports have been more than halved since. Extraterritorial sanctions target foreign firms that would provide services and investment related to the energy sector, including investment in oil and gas fields, sales of equipment used in refining oil, and participation in activities related to oil export, such as shipbuilding, ports operations, and insurance on transport. CISADA and related executive orders expanded restrictions that predated nuclear concerns.

- Trade: The United States has an embargo that prohibits most U.S. firms from trading with or investing in Iran that dates to 1995 [PDF]. Though relaxed in 2000, it was made near-total a decade later. The Obama administration carved out an exception to the embargo for the sale of consumer telecommunications equipment and software.

- Asset freezes and travel bans: Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush froze the assets [PDF] of entities determined to be supporting international terrorism. This list includes dozens of Iranian individuals and institutions, including banks, defense contractors, and the Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Still other sanctions are associated with the aftermath of Iran’s 2009 elections, when security forces suppressed a budding protest movement, and its support for U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organizations. The IRGC’s elite paramilitary Quds Force has been sanctioned for destabilizing Iraq (2007) and abetting human rights abuses in Syria (2011) as Iran lent its support to the government of Bashar al-Assad, whose security forces were putting down what began as a peaceful protest movement.

- Weapons development: The Iran-Iraq Arms Nonproliferation Act (1992) calls for sanctioning any person or entity that assists Tehran in weapons development or acquisition of “chemical, biological, nuclear, or destabilizing numbers and types of advanced conventional weapons.” Subsequent nonproliferation legislation and executive actions have sanctioned individuals and entities assisting WMD production. Additional bans restrict dual-use exports, a justification for an automobile ban, which was waived under the JPA.

The U.S. Congress provides the statutory basis for most U.S. sanctions, but it is up to the executive branch to interpret and implement them. While congressional legislation would be required to repeal these measures, the president, by citing “the national interest,” has the authority to waive nearly all of them in whole or in part. Lifting terrorism-related sanctions would require the president to delist Iran as a state sponsor. The president is also able to hollow them out by removing individuals and entities from sanctions lists.

Because nuclear sanctions would be waived by the executive, rather than repealed by the legislature, in the early years of a prospective agreement, the White House has argued that if Iran violates the agreement, the president can “snap back” sanctions, reinstating them without legislative hurdles.

In May 2015, President Obama signed into law provisions for congressional review that place restrictions on his prerogative to waive sanctions. Under this law, the House and Senate foreign relations committees have sixty days to review the agreement, during which time the president cannot loosen the sanctions regime. But for Congress to derail an agreement, it would not only have to vote it down, but muster a two-thirds majority to override a presidential veto.

What are the UN sanctions?

The UN Security Council has progressively built up an international sanctions regime binding on all its member states ever since the IAEA declared Iran noncompliant with its safeguards obligations in 2005. In a first round of sanctions, in 2006, the Security Council unanimously approved measures that included an embargo on materials and technology used in uranium production and enrichment, as well as in the development of ballistic missiles, and blocked financial transactions abetting the nuclear and ballistic-missile programs.

Subsequent resolutions in 2007 and 2008 blocked no+nhumanitarian financial assistance to Iran and mandated states to inspect cargo suspected of containing prohibited materials, respectively.

A fourth binding resolution, approved in June 2010, tightened the international sanctions regime to its current state. It adopted the U.S. approach, linking Iran’s oil profits and its banking/financial sector, including its central bank, to proliferation efforts, therefore subjecting them to international sanction.

What are the EU sanctions?

The EU has augmented UN penalties against Iran with sanctions that are “nearly as extensive as those of the United States,” according to the nonpartisan U.S.-funded Congressional Research Service (CRS).

A 2007 measure froze the assets of individuals and entities related to Iran’s nuclear and ballistic-missile programs, and prohibited the transfer of dual-use items. In 2010, the EU substantially strengthened its sanctions regime, bringing it into line with U.S. measures by blocking European institutions from transacting with Iranian banks, including its central bank, and restricting trade and investment with the country’s energy and transport sectors, among others.

Brussels’s move to isolate Iran and mount pressure to bring it to negotiations culminated with a 2012 measure banning the import of oil and petrochemical products as well as insurance on shipping, and freezing assets related to Iran’s central bank. A year prior to its 2012 oil embargo, the EU was the largest importer of Iranian oil, averaging six hundred thousand barrels per day, according to the CRS.

The EU agreed to terminate all nuclear-related sanctions in the comprehensive agreement on implementation day. Such changes to EU regulations will require the unanimous consent of the bloc’s twenty-eight member states.

Apart from the nonproliferation sanctions, Brussels has levied sanctions [PDF], including asset freezes and travel bans, for human rights violations, and bans the export of equipment that could be used for telecommunication surveillance or for internal repression.

What has been the impact of sanctions?

International sanctions have taken a severe toll on the Iranian economy. In April 2015, U.S. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew estimated that Iran’s economy was 15 to 20 percent smaller than it would have been had sanctions not been ratcheted up in 2012 and cost $160 billion in lost oil revenue alone. In addition, more than $100 billion in Iranian assets is held in restricted accounts outside the country.

The U.S.-led campaign to ratchet international sanctions threw the economy into a two-year recession, from which it emerged with modest growth in 2014. Meanwhile, the value of the rial declined by 56 percent between January 2012 and January 2014, a period in which inflation reached some 40 percent, according to the CRS. The unemployment rate might be as high as 20 percent. Economic mismanagement under former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and more recently, falling oil prices have also contributed to the economic downturn. The IMF estimates that Iran’s break-even point, the price per barrel at which the country can balance its budget, is $92.50. As of June 1, Brent crude oil sold for $65. Several years of austerity budgets have raised public demands for increased domestic spending, including for oil-industry infrastructure that has fallen into disrepair.

President Hassan Rouhani’s pitch to voters as he campaigned in 2013 was that by negotiating with major powers over Iran’s nuclear program, he could reverse Iran’s economic and diplomatic isolation. With economic reforms and an interim agreement that offered some sanctions relief, he has stabilized the currency and more than halved inflation, but even if the most severe U.S., EU, and multilateral sanctions are lifted with a comprehensive agreement, Iran is unlikely to experience an immediate windfall [PDF], analysts say.

When would sanctions be lifted?

Iran will regain access to international energy markets and the global financial system once the IAEA verifies that it has granted IAEA inspectors sufficient access to nuclear facilities and taken agreed-upon steps to restrict its nuclear program. The comprehensive agreement directs the P5+1 to prepare the legal and administrative groundwork for rescinding or suspending their nuclear-related sanctions prior to implementation day. On implementation day, the UN Security Council will pass a resolution that will nullify previous resolutions on the Iranian nuclear issue.

Negotiators devised a unique mechanism to guard against the possibility that Russia or China, who have shielded Iran from punitive Security Council actions in the past, might block the restoration of sanctions in the event of Iranian noncompliance with a council veto. The agreement calls for an eight-member panel comprising the five permanent members of the Security Council, Germany, the EU, and Iran that is empowered to investigate Iranian noncompliance. The committee could restore UN sanctions within sixty-five days by a majority vote. In such instances, even if China and Russia objected, they could not block the restoration of sanctions.

Iranian negotiators brought the UN embargo on conventional weapons and ballistic missiles under the scope of the comprehensive agreement. These sanctions are poised to be lifted within five and eight years, respectively, though they could be lifted sooner with an IAEA declaration that Iran’s remaining nuclear program serves solely civilian purposes.

Recommended Resources

The full text of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

The U.S. Institute of Peace and Harvard’s Belfer Center have compiled background and analysis on Iran sanctions and other aspects of the nuclear negotiations.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) offers an in-depth look at the U.S. and international sanctions regimes on Iran. A separate CRS report unpacks presidential and congressional authorities with respect to lifting U.S. sanctions on Iran.

This Arms Control Association chart explains the terms of the Joint Plan of Action and tracks the P5+1’s and Iran’s compliance with it.

Then-Undersecretary of the Treasury David S. Cohen outlined the architecture of the U.S. sanctions regime in January 2015 congressional testimony. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew described sanctions in the context of the Obama administration’s negotiating strategy in an April 2015 speech.

The comprehensive agreement will not offer Iran an immediate economic windfall, writes former U.S. sanctions official Richard Nephew [PDF].t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Zachary Laub

Additional Reporting

Header image by Fatemeh Bahrami/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.