From Tiananmen to COVID: Modern China’s Protests in Photos

China’s citizens have mounted protests big and small to challenge authority in recent decades. While the catalyst for November’s protests was the zero-COVID policy, past demonstrations have focused on religious freedom, environmental protection, and more.

Thousands of people took to China’s streets in November 2022 to denounce the government’s strict zero-COVID policy, displaying blank sheets of paper and raising flower bouquets into the air. Reaching more than a dozen cities, these were China’s most widespread demonstrations to target the country’s top leaders since 1989, when the government crushed the Tiananmen Square protests.

Since then, Beijing has worked to quell most dissent. President Xi Jinping has gone further than previous leaders, overseeing the imprisonment of human rights activists, an increase in internet censorship and surveillance, and the harassment of journalists and academics.

Despite this ramped-up repression, protests still happen every day in mainland China, though they usually focus on local issues and have rarely reached the scale of the November demonstrations. Over the years, people have gathered to call for workplace protections, reparations for man-made disasters, and many other causes. Some were successful, while others were ignored or even repressed.

Here’s a look at protests in the country since 1989—and what drives activists to stand up against all odds.

June 1989

Thousands of students, workers, and other citizens spent weeks peacefully protesting for political and economic reform in the spring of 1989. On June 4, Chinese troops entered Tiananmen Square and opened fire, launching a massive crackdown. The estimated death toll ranges from the hundreds to the thousands, and human rights groups believe that as many as ten thousand people were detained.

April 1999

More than ten thousand practitioners of Falun Gong, a spiritual movement based on traditional qigong exercise, protested peacefully outside Chinese Communist Party headquarters in Beijing in response to a crackdown that started several years earlier. The government vowed to eliminate the movement, which it called an “evil cult,” and jailed thousands of people.

March 2008

Monks and ethnic Tibetans marched in cities throughout western China to commemorate the forty-ninth anniversary of the Tibetan uprising. Rights organizations say security forces responded violently to protests in Tibet’s capital, Lhasa, where rioting broke out, and Gansu Province’s Xiahe region. In this photo, protesters carry the Tibetan flag in Xiahe.

May 2008

Thousands of children were among those killed when a devastating earthquake in Sichuan Province caused poorly built schools to collapse. In the aftermath, mourning parents protested unsafe school construction in defiance of local authorities. The central government said it would investigate the schools’ collapse, but later blamed the student deaths on natural causes.

July 2009

Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group living in the northwestern Xinjiang region, flooded the regional capital’s streets to protest state-incentivized Han Chinese migration and widespread economic and cultural discrimination. Riots broke out as security forces responded, and nearly two hundred people were killed. In recent years, the government has been accused of arbitrarily detaining at least one million Muslims in reeducation camps.

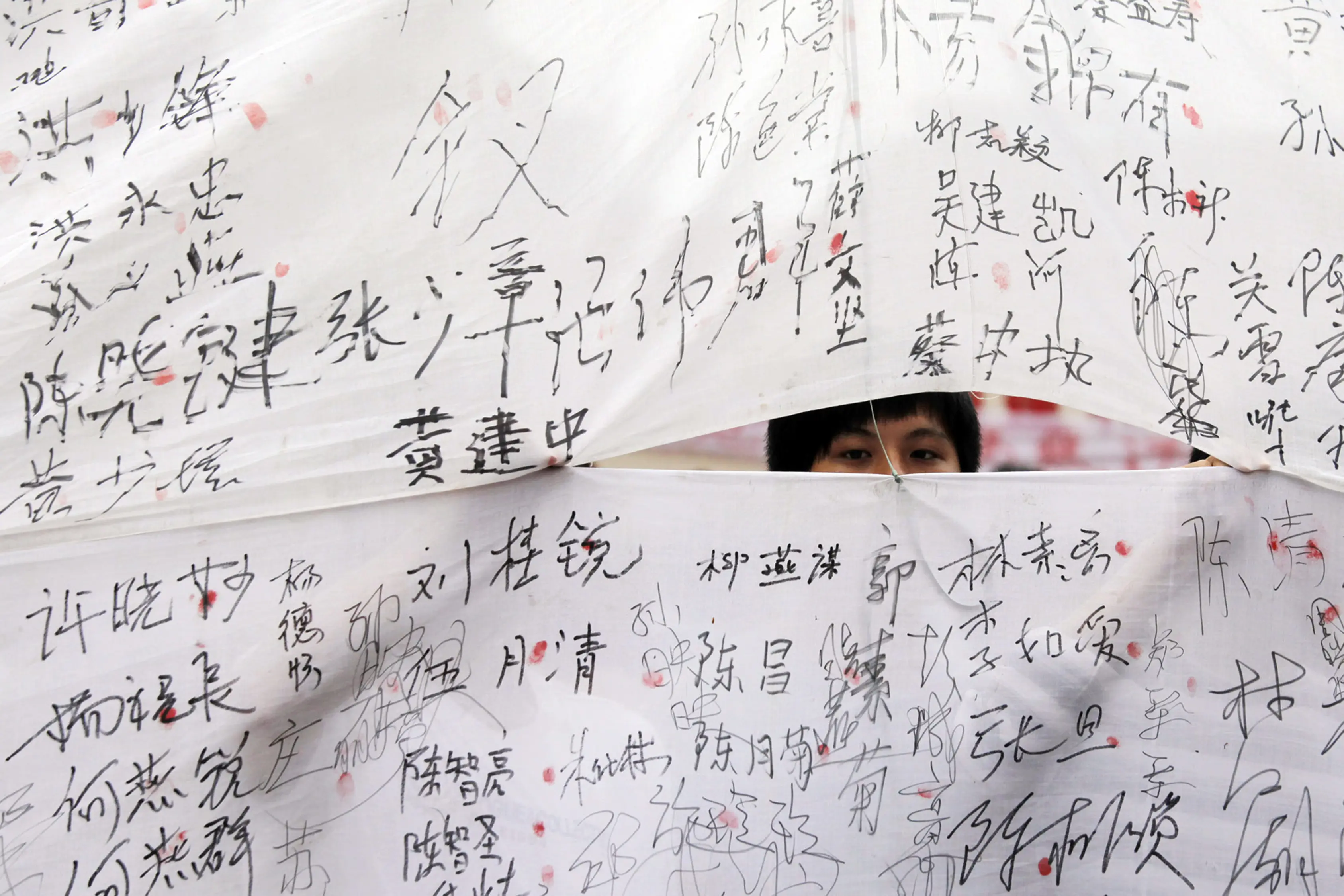

December 2009

International activists, foreign governments, and Chinese supporters, seen in this photo, protested on behalf of Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize winner and democracy advocate. Liu helped draft Charter 08, a petition calling for respect of basic human rights. Despite the protests, Liu was sentenced to eleven years in prison, and he died in Chinese custody in 2017.

June 2010

Workers in many industries have frequently mobilized against state-owned companies, local bosses, and factory owners. The Hong Kong–based nonprofit China Labour Bulletin estimates that there have been thousands of labor protests in the country since 2011. In this photo, employees strike over low wages and working conditions at a Honda factory in Guangdong Province.

September 2011

Demonstrating against what they called illegal land sales, protesters temporarily forced police and other officials out of Wukan, a fishing village in southern Guangdong Province. In a compromise, authorities agreed to hold local democratic elections and to investigate the land sales. Years later, villagers protested again, saying they hadn’t gotten their land back.

July 2012

About one thousand people occupied a government building in the port city of Qidong to protest the construction of a pipeline that would have emptied industrial waste from a paper factory into the East China Sea. The project was canceled soon after. Environmental protests have been organized throughout China as residents suffer from poor health caused by widespread pollution.

August 2015

One of the deadliest accidents in years, explosions at a chemical warehouse in the city of Tianjin killed more than 170 people and destroyed hundreds of homes. Survivors demanded that the government fully compensate them for damages, but journalists reported a year later that some residents were still living among the rubble. Chemical accidents such as this are common in China, with Greenpeace estimating that 232 accidents occurred over just eight months in 2016.

October 2016

Hundreds of former service members called for better benefits and protested against spending cuts outside of the Defense Ministry in Beijing—one of many veterans’ protests in recent years—but the government responded only by issuing a vague statement.

December 2018

Many protesters have turned to rights lawyers to defend their cases. But in July 2015, the lawyers became victims themselves as the government launched a crackdown, questioning and detaining nearly 250 people, according to human rights groups. The wives of four lawyers shaved their heads to protest their husbands’ treatment in detention. The lawyers—Li Heping, Wang Quanzhang, Xie Yanyi, and Zhai Yanmin—were eventually released.

July 2022

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Chinese government’s strict zero-COVID policy have battered China’s economy, making some people quick to protest over financial issues. In July, people demonstrated outside of a government office in the city of Zhengzhou, demanding to withdraw their savings after local banks froze transactions in a possible fraud scandal. In November in the same city, workers at a Foxconn factory pushed for better pay and working conditions.

November 2022

COVID-19 controls have intermittently sparked public outrage. By 2022, some people had come to resent the government’s zero-COVID policy and express anger at the Chinese Communist Party’s total control over their lives. The largest and most widespread protests occurred in November in more than a dozen cities, including at major universities. They came in response to a deadly apartment fire in the Xinjiang region’s capital, Urumqi; many protesters said the victims were prevented from exiting the building because it was locked down. While the protests began with vigils for the victims and calls for an end to COVID-19 testing and lockdowns, their criticism increasingly targeted the country’s leaders, including Xi, and included broad demands for more freedom.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in May 2019 and was updated in December 2022 to include protests against China’s zero-COVID policy.

Online Store

Online Store