Visualizing 2023: Trends to Watch

Using charts, CFR experts track developments that could shape the year ahead.

Last updated December 9, 2022 4:26 pm (EST)

- Article

- Current political and economic issues succinctly explained.

Five CFR fellows highlight in charts and graphs some of the most pressing trends to follow in 2023, including the Asia-Pacific’s arms race, the changing relationship between India and Russia, and worsening brain drain in sub-Saharan Africa.

Food Price Inflation

More on:

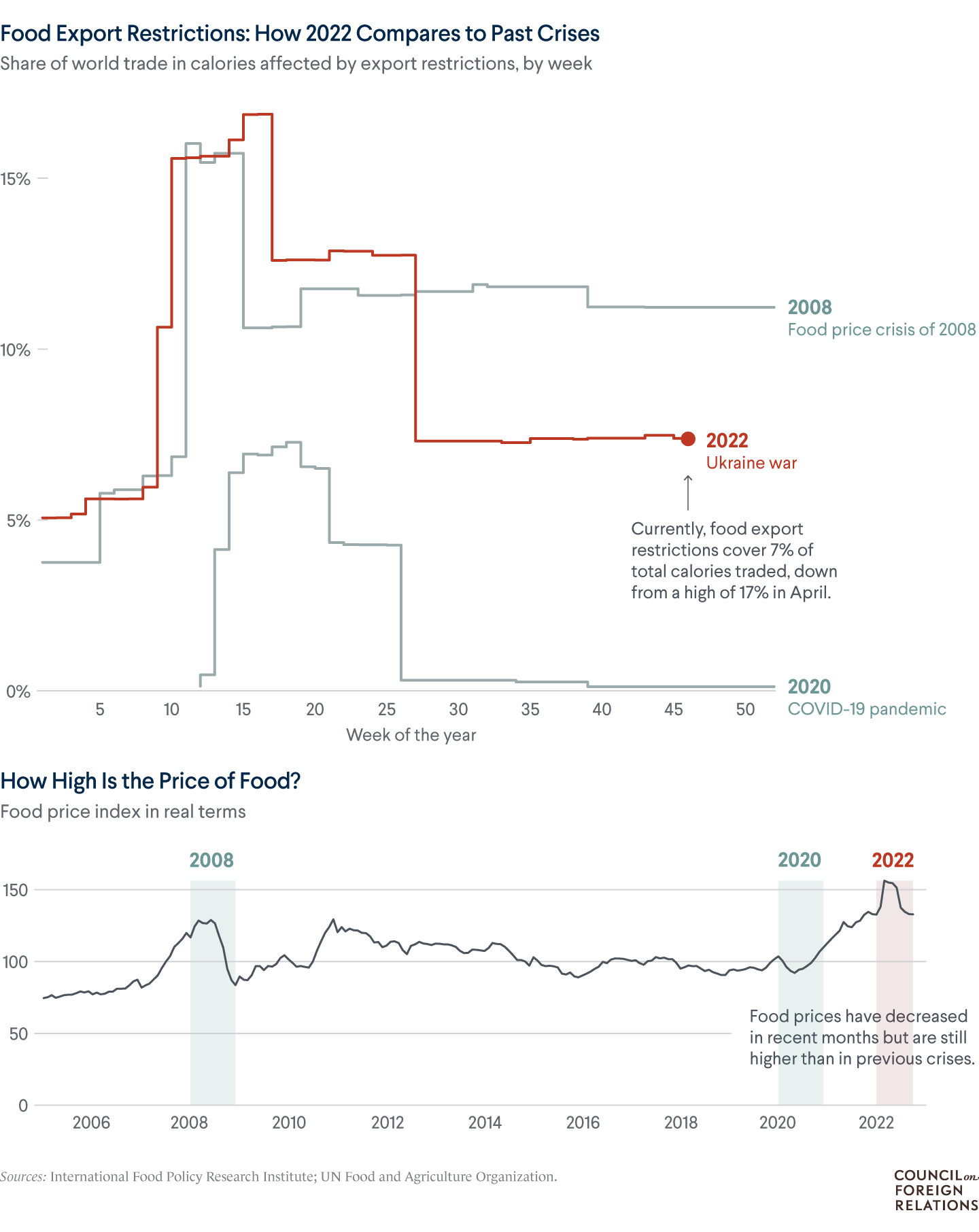

Food insecurity was a persistent problem in 2022 and, without concerted international efforts to tackle it, will continue to be so in 2023. Over 820 million people—more than 10 percent of the world’s population—go to bed hungry each night. Today’s food insecurity is a product of various factors, including regional conflicts and climate shocks, and Russia’s war in Ukraine has exacerbated the crisis. Food costs have soared to their highest levels [PDF] in over ten years.

In response to these troubling dynamics, countries quickly ramped up export restrictions early in the year, particularly on food and fertilizers, only to pull some back in the following weeks. Tracking by the International Food Policy Research Institute shows that twenty-one countries maintain food export restrictions, covering 7 percent of global trade in calories. Many of these were imposed by Group of Twenty (G20) countries, a collection of the world’s largest economies. In fact, just over half of all food export restrictions are from G20 economies. That said, the share of traded calories affected by export restrictions has dropped well below the levels experienced during the 2008 food price crisis, though single interventions can cause large fluctuations. For instance, Indonesia’s decision this past May to lift its controversial ban on palm oil exports, which covered goods ranging from food products to cosmetics, helps explain the sudden midyear drop in overall restrictions.

The war in Ukraine has significantly disrupted grain shipments, risking famine in countries that are highly dependent on such imports, such as Yemen. Western sanctions against Russia and its ally Belarus have also played a role in reducing access to certain agricultural products. As long as the war continues, food price inflation will likely endure. In the meantime, countries can help by increasing financial support to the World Food Program, removing export restrictions and trade-distorting agricultural subsidies, and working to develop more sustainable agricultural practices.

Inu Manak is the fellow for trade policy.

China’s Military Dominance in the Asia-Pacific

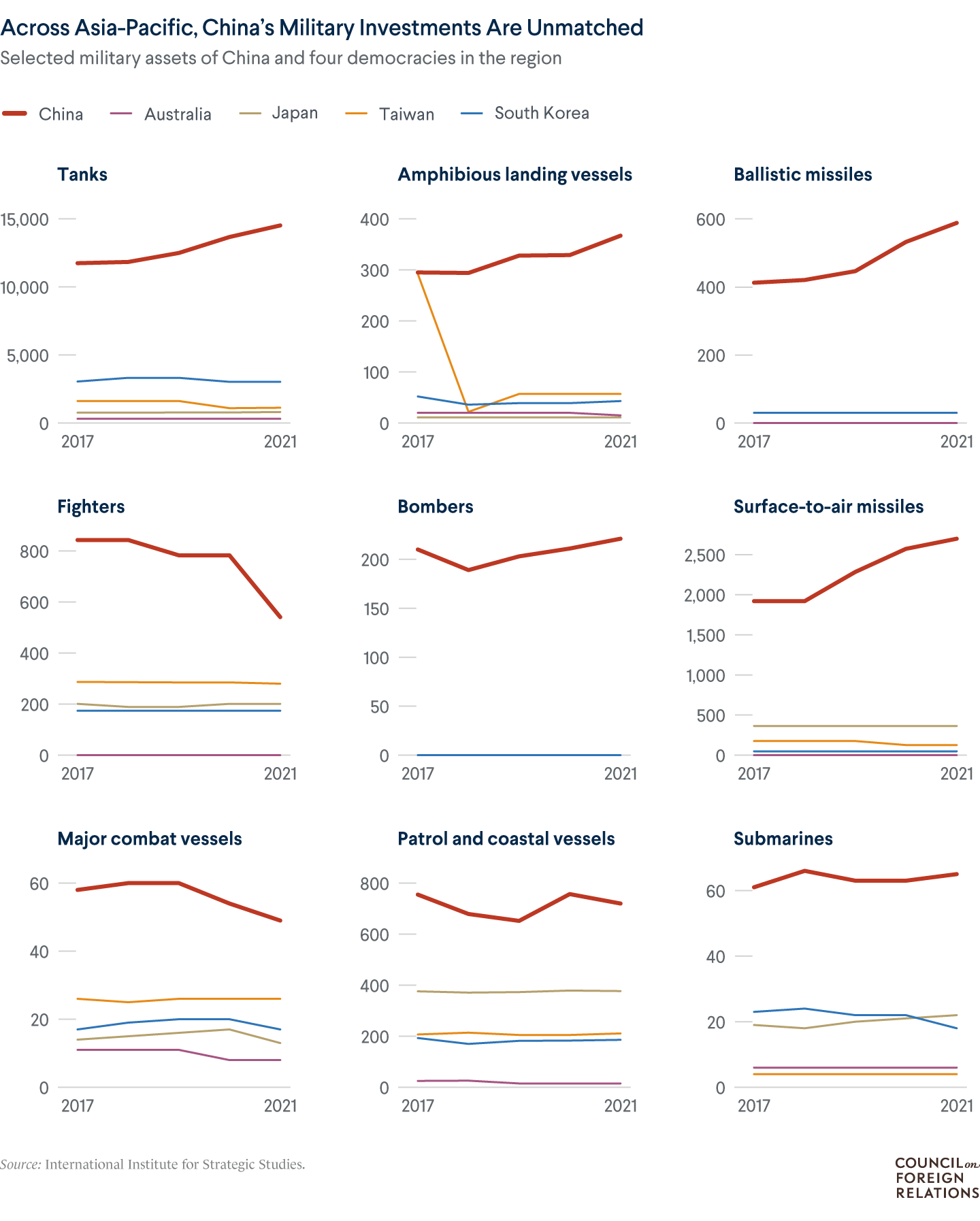

China’s military buildup in the Asia-Pacific in recent years has raised concerns in the West about Beijing’s security aims. The United States and its regional partners are growing increasingly wary of the potential for China to invade Taiwan or take aggressive actions in the South China Sea. However, U.S. allies in the area appear ill-prepared to counter major military challenges by Beijing.

More on:

In the past five years, China’s military spending has gone up by 25 percent, slightly higher than even the United States’ increase. Much of this investment is concentrated in military platforms designed for offensive amphibious assaults and overseas occupation.

But U.S. allies and partners in the Asia-Pacific do not appear to be responding in kind. The governments of Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are not investing as much in the same military capabilities as China, nor in those necessary to combat or deter Chinese expansion [PDF], including air defenses and naval patrol vessels. Even Taiwan, which faces among the most immediate threats, has yet to spend more on defense despite the United States urging it to do so. At minimum, these countries should be concerned about the possible effects of China expanding its sphere of influence in terms of trade and access to natural resources. Apart from Japan’s growing investment in submarines, many non-Chinese militaries in the region look roughly the same as they did five years ago.

If U.S. concerns about what China can accomplish with these new investments are well founded, these Asia-Pacific countries are either behind in developing the military power needed to counter Chinese aggression, or they are supremely confident that the United States will come to their aid in a conflict. (Australia, Japan, and South Korea have mutual defense pacts with the United States.) Recent joint military exercises and defense summits suggest the latter: U.S. partners in the Asia-Pacific remain confident that when push comes to shove, their relationships with the United States will ensure their security against China.

J. Andrés Gannon is the Stanton nuclear security fellow.

Shifting Relations Between India and Russia

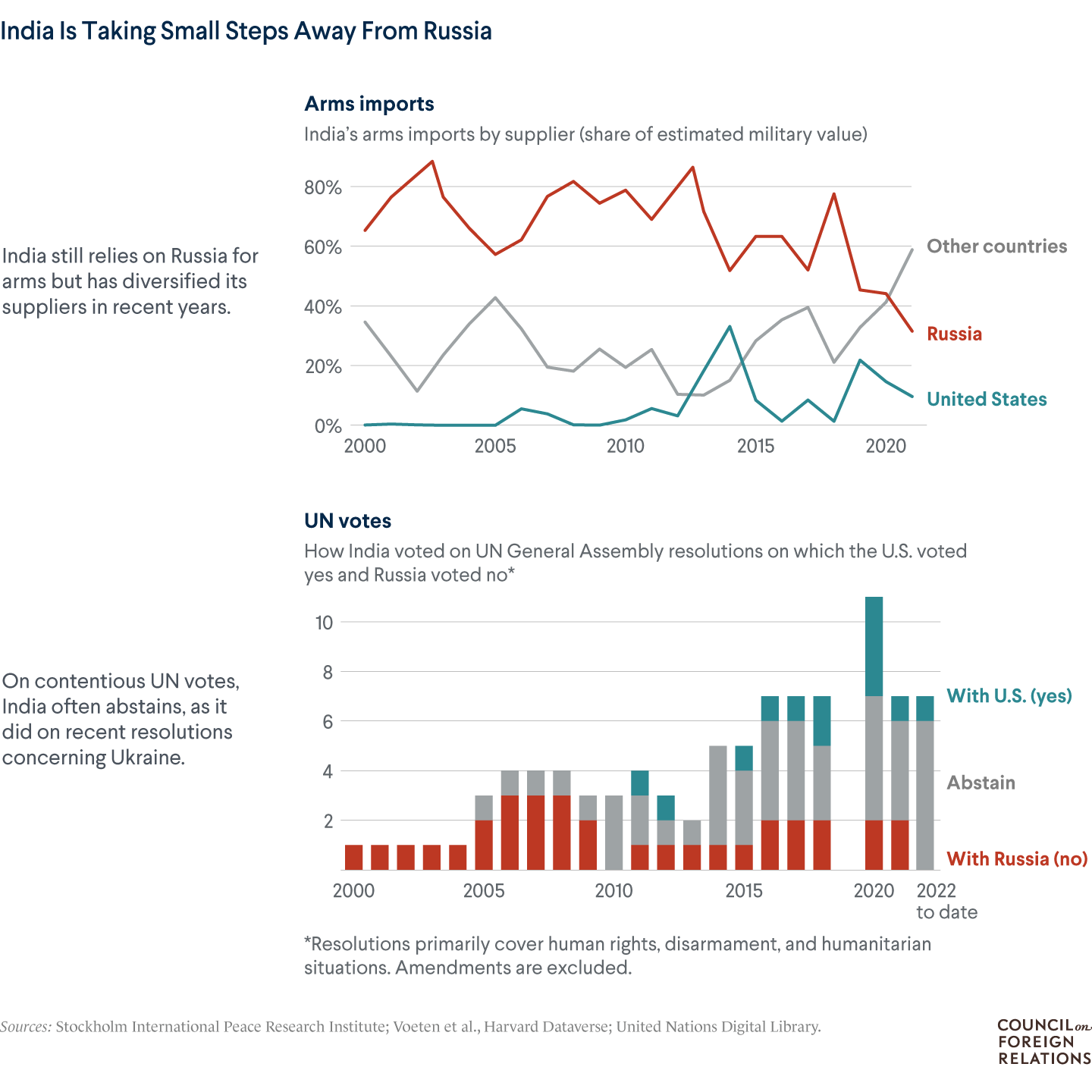

Russia’s war in Ukraine has put renewed diplomatic pressure on New Delhi to reexamine its long-standing relationship with Moscow. Some experts say Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s public rebuke of Russian President Vladimir Putin at a regional summit in September signified a historic break in the friendship. Others counter that India’s surging purchases of Russian oil in recent months indicate that ties are actually getting stronger. A look at important trend lines illustrates that a more subtle shift in relations is taking place.

During the Cold War, India and the Soviet Union maintained strong economic and military relations, with New Delhi sourcing most of its arms from Moscow. This robust trade continued in the years after the Soviet collapse, until the mid-2010s, when India began to slowly diversify its sources. By 2020, the majority of India’s arms came from other countries, including France, Israel, and the United States. Still, decades of Soviet military support means that much of India’s military hardware today is Russian, so India has to depend on Russia for software, repairs, and upgrades.

Meanwhile, India’s voting history at the UN General Assembly over the past twenty years shows that on many divisive resolutions, including those concerning human rights and disarmament, it repeatedly sided with Russia. But here, too, a subtle shift is occurring. Since 2010, India has occasionally voted with the United States, and it has largely abstained from resolutions that displayed stark divisions between Moscow and Washington.

On trade more broadly, the boom in India’s purchases of Russian oil is not indicative of a greater warming of bilateral ties, but rather an example of how New Delhi is willing to take advantage of a financial opportunity with Moscow—in this case, heavily discounted oil. India’s overall trade with Russia, however, remains underwhelming when compared to that with partners such as the United States.

Manjari Chatterjee Miller is the senior fellow for India, Pakistan, and South Asia.

Nigeria’s Brain Drain

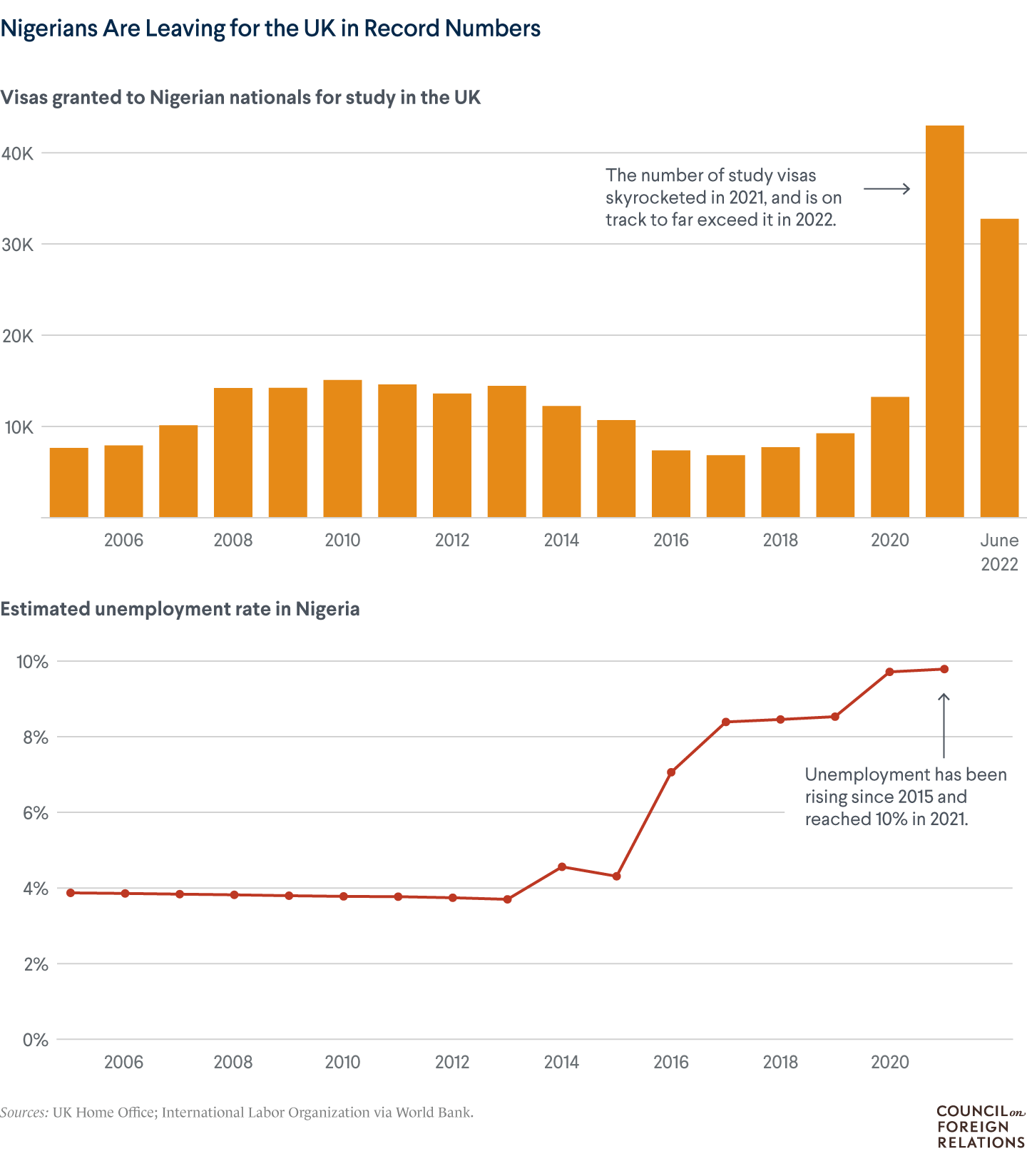

Nigeria is in the midst of an alarming, decades-long brain drain of students. In the past few years, it has escalated further: since 2020, the number of student visas granted to Nigerians by the United Kingdom (UK) has increased fourfold, reaching a high of almost forty-three thousand in 2021. The two countries have ties dating back to the colonial era and a common language (English is the lingua franca in Nigeria), which make the UK the top destination for Nigerian students. Several factors in Nigeria are driving this surge in emigration, including instability in the education sector; declining quality of life; poor infrastructure; corruption; and a worsening job market, which has seen the youth unemployment rate spike to almost 43 percent.

This phenomenon is indicative of a larger trend in which Nigerian students—more so than their peers in the rest of Africa—are flocking to Western countries, including the United States, in pursuit of higher education and better life prospects overall. Indeed, nearly half of Nigerian adults surveyed in 2019 by Pew Research Center said they were planning on moving abroad in the next five years.

Reversing this trend will require the Nigerian government and private sector to make significant investments in physical infrastructure across the education system, as well as increase collaboration with international and local stakeholders. More broadly, Nigeria should make greater investments in infrastructure at large, security, and job creation to encourage more young Nigerians to imagine a future in their country.

Ebenezer Obadare is the Douglas Dillon senior fellow for Africa Studies.

The Growing U.S. Political Divide

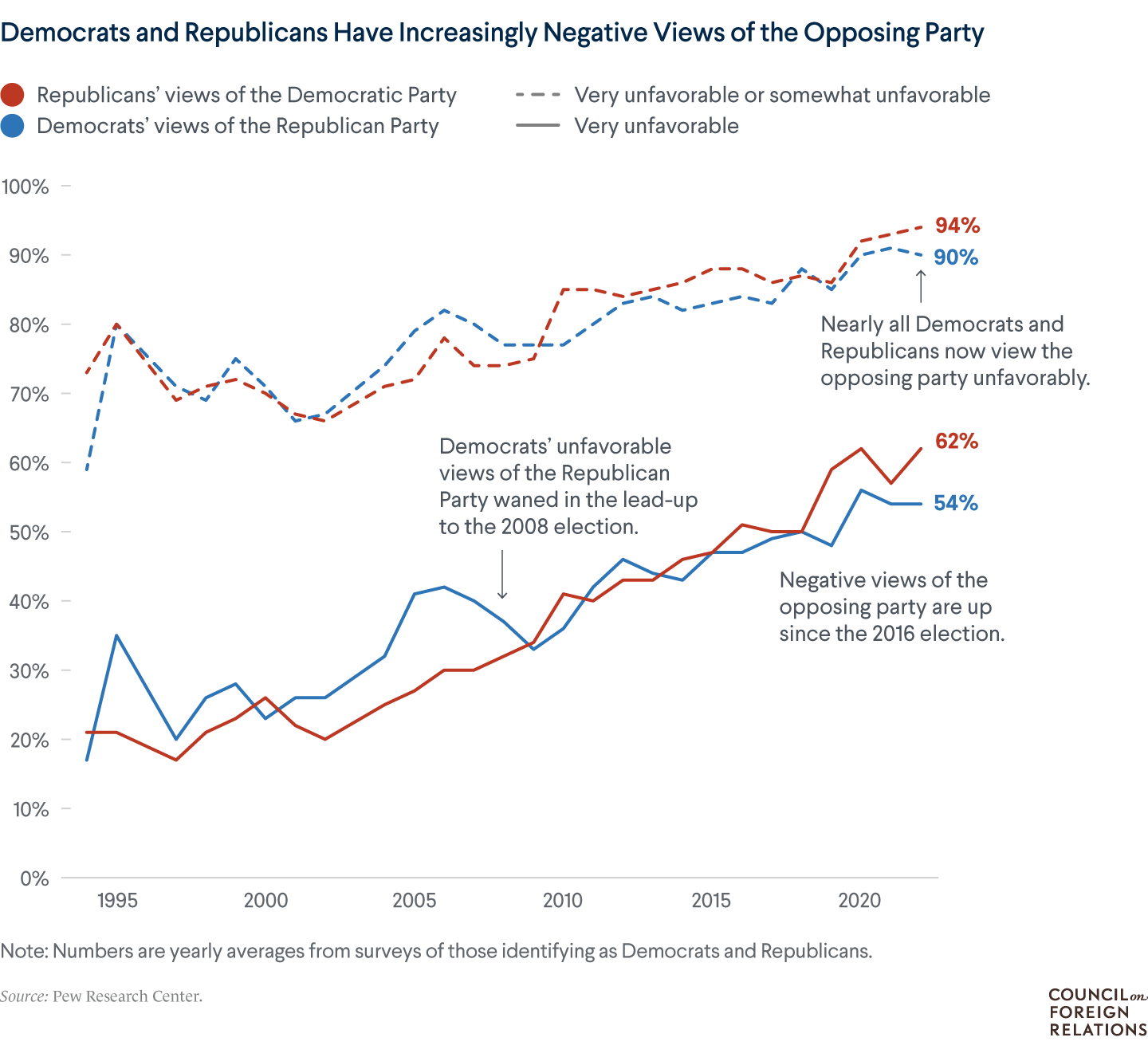

The first thing that might spring to mind when looking at the accelerating political polarization in the United States—particularly increasingly negative views of the opposing party held by both Democrats and Republicans—is the emergence of Trumpism on the American political scene. But data indicates that former President Donald Trump is likely less a cause and more a symptom of the divisions plaguing the United States. Today’s hyperpolarization has been decades in the making, rising alarmingly since the early 1990s.

Trumpism undoubtedly intensified the domestic discord. For example, majorities of both major parties now hold troubling views about Americans on the other side of the political spectrum, describing them with terms such as “unintelligent,” “dishonest,” and “immoral.” While that’s a significant escalation from six years ago, the longer-term trends are equally discouraging, revealing that U.S. democracy would likely still be in a tough place had the Trump era never transpired.

The reaction by political analysts to last month’s midterm elections—which saw the defeat of dozens of high-profile, Trump-backed candidates—has largely been relief, with many speculating about the decline of Trump and a corresponding “return to normalcy.” But in the fifteen years preceding Trump’s entry into the 2016 presidential campaign, the proportion of Americans holding “very unfavorable” views of the other side nearly doubled. If a return to normalcy means that trajectory will continue unabated in a post-Trump America, that’s not good news.

Perhaps Trump marked a peak for U.S. political polarization, and the fever has finally begun to break. More likely, however, is that even if Trump’s influence wanes in the year ahead, Americans will still find themselves in a political environment similar to what existed before he announced his candidacy in 2016, and that’s no cause for optimism.

Christopher M. Tuttle is a senior fellow and the director of the Renewing America initiative.

Will Merrow created the graphics for this article.

Online Store

Online Store