How the Obama Administration Justifies Targeted Killings

More on:

Despite almost ten years of operations and nearly four hundred airstrikes that killed an estimated three thousand people (both militants and civilians), both the Bush and Obama administrations have provided limited information about U.S. targeted killings policies. The scope and intensity of the strikes represent an undeclared Third War beyond Afghanistan and Iraq, for which policymakers offer adjectives (“surgical,” “discriminate,” targeted,” and “precise”) but refuse to directly address any questions. According to White House spokesperson Jay Carney in February, “I’m not going to discuss broadly or specifically supposed covert programs.”

A year into office, the Obama administration began to authorize policy speeches about targeted killings. As David Sanger revealed in his recent book Confront and Conceal: Obama’s Secret Wars and Surprising Use of American Power:

“By early 2010—a year after Obama had ordered a major increase in the pace of drone strikes in Pakistan, and as the success of that program in eliminating al-Qaeda’s middle management was becoming clear—the lawyers were giving the job of coming up with an acceptable public justification for [targeted killings].”

Beginning with the speech given by Harold Koh in March 2010, there have been seven significant on-the-record statements or speeches that encompass the sole public rationale for U.S. targeted killings policy. When asked to articulate some aspect of this policy, administration staffers or officials will point you to one or all of these. In order to better understand the justification for U.S. targeted killings, I have posted the relevant selections with links to the full speeches below.

Harold Koh, Legal Adviser, U.S. Department of State

March 25, 2010: Annual Meeting of the American Society of International Law

In the same way, in all of our operations involving the use of force, including those in the armed conflict with al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and associated forces, the Obama administration is committed by word and deed to conducting ourselves in accordance with all applicable law. With respect to the subject of targeting, which has been much commented upon in the media and international legal circles, there are obviously limits to what I can say publicly. What I can say is that it is the considered view of this administration—and it has certainly been my experience during my time as legal adviser—that U.S. targeting practices, including lethal operations conducted with the use of unmanned aerial vehicles, comply with all applicable law, including the laws of war.

Second, some have challenged the very use of advanced weapons systems, such as unmanned aerial vehicles, for lethal operations. But the rules that govern targeting do not turn on the type of weapon system used, and there is no prohibition under the laws of war on the use of technologically advanced weapons systems in armed conflict-- such as pilotless aircraft or so-called smart bombs-- so long as they are employed in conformity with applicable laws of war. Indeed, using such advanced technologies can ensure both that the best intelligence is available for planning operations, and that civilian casualties are minimized in carrying out such operations.

Third, some have argued that the use of lethal force against specific individuals fails to provide adequate process and thus constitutes unlawful extrajudicial killing. But a state that is engaged in an armed conflict or in legitimate self-defense is not required to provide targets with legal process before the state may use lethal force. Our procedures and practices for identifying lawful targets are extremely robust, and advanced technologies have helped to make our targeting even more precise. In my experience, the principles of distinction and proportionality that the United States applies are not just recited at meetings. They are implemented rigorously throughout the planning and execution of lethal operations to ensure that such operations are conducted in accordance with all applicable law.

Fourth and finally, some have argued that our targeting practices violate domestic law, in particular, the long-standing domestic ban on assassinations. But under domestic law, the use of lawful weapons systems—consistent with the applicable laws of war—for precision targeting of specific high-level belligerent leaders when acting in self-defense or during an armed conflict is not unlawful, and hence does not constitute “assassination.” In sum, let me repeat: as in the area of detention operations, this Administration is committed to ensuring that the targeting practices that I have described are lawful.

John O. Brennan, Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism

September 16, 2011: Remarks at Harvard Law School

First, our definition of the conflict. As the President has said many times, we are at war with al-Qa’ida. In an indisputable act of aggression, al-Qa’ida attacked our nation and killed nearly 3,000 innocent people. And as we were reminded just last weekend, al-Qa’ida seeks to attack us again. Our ongoing armed conflict with al-Qa’ida stems from our right—recognized under international law—to self defense.

An area in which there is some disagreement is the geographic scope of the conflict. The United States does not view our authority to use military force against al-Qa’ida as being restricted solely to “hot” battlefields like Afghanistan. Because we are engaged in an armed conflict with al-Qa’ida, the United States takes the legal position that —in accordance with international law—we have the authority to take action against al-Qa’ida and its associated forces without doing a separate self-defense analysis each time. And as President Obama has stated on numerous occasions, we reserve the right to take unilateral action if or when other governments are unwilling or unable to take the necessary actions themselves.

That does not mean we can use military force whenever we want, wherever we want. International legal principles, including respect for a state’s sovereignty and the laws of war, impose important constraints on our ability to act unilaterally—and on the way in which we can use force—in foreign territories.

Others in the international community—including some of our closest allies and partners—take a different view of the geographic scope of the conflict, limiting it only to the “hot” battlefields. As such, they argue that, outside of these two active theatres, the United States can only act in self-defense against al-Qa’ida when they are planning, engaging in, or threatening an armed attack against U.S. interests if it amounts to an “imminent” threat.

In practice, the U.S. approach to targeting in the conflict with al-Qa’ida is far more aligned with our allies’ approach than many assume. This Administration’s counterterrorism efforts outside of Afghanistan and Iraq are focused on those individuals who are a threat to the United States, whose removal would cause a significant – even if only temporary – disruption of the plans and capabilities of al-Qa’ida and its associated forces. Practically speaking, then, the question turns principally on how you define “imminence.”

We are finding increasing recognition in the international community that a more flexible understanding of “imminence” may be appropriate when dealing with terrorist groups, in part because threats posed by non-state actors do not present themselves in the ways that evidenced imminence in more traditional conflicts. After all, al-Qa’ida does not follow a traditional command structure, wear uniforms, carry its arms openly, or mass its troops at the borders of the nations it attacks. Nonetheless, it possesses the demonstrated capability to strike with little notice and cause significant civilian or military casualties. Over time, an increasing number of our international counterterrorism partners have begun to recognize that the traditional conception of what constitutes an “imminent” attack should be broadened in light of the modern-day capabilities, techniques, and technological innovations of terrorist organizations.

The convergence of our legal views with those of our international partners matters. The effectiveness of our counterterrorism activities depends on the assistance and cooperation of our allies—who, in ways public and private, take great risks to aid us in this fight. But their participation must be consistent with their laws, including their interpretation of international law. Again, we will never abdicate the security of the United States to a foreign country or refrain from taking action when appropriate. But we cannot ignore the reality that cooperative counterterrorism activities are a key to our national defense. The more our views and our allies’ views on these questions converge, without constraining our flexibility, the safer we will be as a country.

President Barack Obama

January 30, 2012: Google+ “Hangout”

I want to make sure that the people understand actually that drones have not caused a huge amount of civilian casualties. For the most part, they have been very precise, precision strikes against al-Qaeda and their affiliates and we are very careful in terms of how its been applied. I think there is this perception somehow that we’re just sending in a whole bunch of strikes willy-nilly. This is a targeted, focused effort at people who are on a list of active terrorists who are trying to go in and harm Americans, hit American facilities, American bases, and so on. It is important for everybody to understand that this thing is kept on a very tight leash. It’s not a bunch of folks in a room somewhere just making decisions. It is also part and parcel of our overall authority when it comes to battling al-Qaeda. It is not something that is being used beyond that.

We have to be judicious in how we use drones. But understand that probably our ability to respect the sovereignty of other countries and to limit our incursions into somebody else’s territory is enhanced by the fact that we are able to pinpoint strike an al-Qaeda operative in a place where the capacities of that military and that country might not be able to get them. Obviously a lot of these strikes have been in the Fataah and going after al-Qaeda suspects who are up in very tough terrain along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. For us to be able to get them in another way would involve probably a lot more intrusive military actions than the one we’re already engaging in. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be careful about how we proceed on this and obviously I’m looking forward to a time where al-Qaeda is no longer an operative network and we can refocus a lot of our assets and attention on other issues.

Jeh Johnson, General Counsel of the Department of Defense

February 22, 2012: Dean’s Lecture at Yale Law School

Should the legal assessment of targeting a single identifiable military objective be any different in 2012 than it was in 1943, when the U.S. Navy targeted and shot down over the Pacific the aircraft flying Admiral Yamamoto, the commander of the Japanese navy during World War Two, with the specific intent of killing him? Should we take a dimmer view of the legality of lethal force directed against individual members of the enemy, because modern technology makes our weapons more precise? As Harold stated two years ago, the rules that govern targeting do not turn on the type of weapon system used, and there is no prohibition under the law of war on the use of technologically advanced weapons systems in armed conflict, so long as they are employed in conformity with the law of war. Advanced technology can ensure both that the best intelligence is available for planning operations, and that civilian casualties are minimized in carrying out such operations.

On occasion, I read or hear a commentator loosely refer to lethal force against a valid military objective with the pejorative term “assassination.” Like any American shaped by national events in 1963 and 1968, the term is to me one of the most repugnant in our vocabulary, and it should be rejected in this context. Under well-settled legal principles, lethal force against a valid military objective, in an armed conflict, is consistent with the law of war and does not, by definition, constitute an “assassination.”

Fifth: as I stated at the public meeting of the ABA Standing Committee on Law and National Security, belligerents who also happen to be U.S. citizens do not enjoy immunity where non-citizen belligerents are valid military objectives. Reiterating principles from Ex Parte Quirin in 1942, the Supreme Court in 2004, in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, stated that “[a] citizen, no less than an alien, can be ‘part of or supporting forces hostile to the United States or coalition partners’ and ‘engaged in an armed conflict against the United States.’”

Sixth: contrary to the view of some, targeting decisions are not appropriate for submission to a court. In my view, they are core functions of the Executive Branch, and often require real-time decisions based on an evolving intelligence picture that only the Executive Branch may timely possess. I agree with Judge Bates of the federal district court in Washington, who ruled in 2010 that the judicial branch of government is simply not equipped to become involved in targeting decisions.

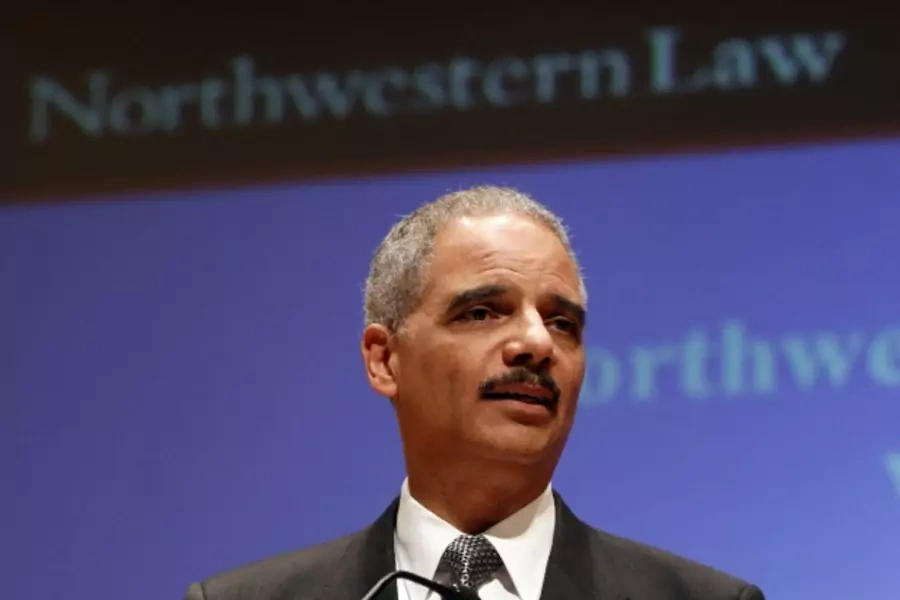

Eric Holder, Attorney General

March 5, 2012: Remarks at Northwestern University School of Law

This principle has long been established under both U.S. and international law. In response to the attacks perpetrated – and the continuing threat posed – by al Qaeda, the Taliban, and associated forces, Congress has authorized the President to use all necessary and appropriate force against those groups. Because the United States is in an armed conflict, we are authorized to take action against enemy belligerents under international law. The Constitution empowers the President to protect the nation from any imminent threat of violent attack. And international law recognizes the inherent right of national self-defense. None of this is changed by the fact that we are not in a conventional war.

Our legal authority is not limited to the battlefields in Afghanistan. Indeed, neither Congress nor our federal courts has limited the geographic scope of our ability to use force to the current conflict in Afghanistan. We are at war with a stateless enemy, prone to shifting operations from country to country. Over the last three years alone, al Qaeda and its associates have directed several attacks – fortunately, unsuccessful – against us from countries other than Afghanistan. Our government has both a responsibility and a right to protect this nation and its people from such threats.

This does not mean that we can use military force whenever or wherever we want. International legal principles, including respect for another nation’s sovereignty, constrain our ability to act unilaterally. But the use of force in foreign territory would be consistent with these international legal principles if conducted, for example, with the consent of the nation involved – or after a determination that the nation is unable or unwilling to deal effectively with a threat to the United States.

Furthermore, it is entirely lawful – under both United States law and applicable law of war principles – to target specific senior operational leaders of al Qaeda and associated forces. This is not a novel concept. In fact, during World War II, the United States tracked the plane flying Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto – the commander of Japanese forces in the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway – and shot it down specifically because he was on board. As I explained to the Senate Judiciary Committee following the operation that killed Osama bin Laden, the same rules apply today.

Some have called such operations “assassinations.” They are not, and the use of that loaded term is misplaced. Assassinations are unlawful killings. Here, for the reasons I have given, the U.S. government’s use of lethal force in self defense against a leader of al Qaeda or an associated force who presents an imminent threat of violent attack would not be unlawful — and therefore would not violate the Executive Order banning assassination or criminal statutes.

Now, it is an unfortunate but undeniable fact that some of the threats we face come from a small number of United States citizens who have decided to commit violent attacks against their own country from abroad. Based on generations-old legal principles and Supreme Court decisions handed down during World War II, as well as during this current conflict, it’s clear that United States citizenship alone does not make such individuals immune from being targeted. But it does mean that the government must take into account all relevant constitutional considerations with respect to United States citizens – even those who are leading efforts to kill innocent Americans. Of these, the most relevant is the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, which says that the government may not deprive a citizen of his or her life without due process of law.

The Supreme Court has made clear that the Due Process Clause does not impose one-size-fits-all requirements, but instead mandates procedural safeguards that depend on specific circumstances. In cases arising under the Due Process Clause – including in a case involving a U.S. citizen captured in the conflict against al Qaeda – the Court has applied a balancing approach, weighing the private interest that will be affected against the interest the government is trying to protect, and the burdens the government would face in providing additional process. Where national security operations are at stake, due process takes into account the realities of combat.

Here, the interests on both sides of the scale are extraordinarily weighty. An individual’s interest in making sure that the government does not target him erroneously could not be more significant. Yet it is imperative for the government to counter threats posed by senior operational leaders of al Qaeda, and to protect the innocent people whose lives could be lost in their attacks.

Any decision to use lethal force against a United States citizen – even one intent on murdering Americans and who has become an operational leader of al-Qaeda in a foreign land – is among the gravest that government leaders can face. The American people can be – and deserve to be – assured that actions taken in their defense are consistent with their values and their laws. So, although I cannot discuss or confirm any particular program or operation, I believe it is important to explain these legal principles publicly.

Let me be clear: an operation using lethal force in a foreign country, targeted against a U.S. citizen who is a senior operational leader of al Qaeda or associated forces, and who is actively engaged in planning to kill Americans, would be lawful at least in the following circumstances: First, the U.S. government has determined, after a thorough and careful review, that the individual poses an imminent threat of violent attack against the United States; second, capture is not feasible; and third, the operation would be conducted in a manner consistent with applicable law of war principles.

The evaluation of whether an individual presents an “imminent threat” incorporates considerations of the relevant window of opportunity to act, the possible harm that missing the window would cause to civilians, and the likelihood of heading off future disastrous attacks against the United States. As we learned on 9/11, al Qaeda has demonstrated the ability to strike with little or no notice – and to cause devastating casualties. Its leaders are continually planning attacks against the United States, and they do not behave like a traditional military – wearing uniforms, carrying arms openly, or massing forces in preparation for an attack. Given these facts, the Constitution does not require the President to delay action until some theoretical end-stage of planning – when the precise time, place, and manner of an attack become clear. Such a requirement would create an unacceptably high risk that our efforts would fail, and that Americans would be killed.

Whether the capture of a U.S. citizen terrorist is feasible is a fact-specific, and potentially time-sensitive, question. It may depend on, among other things, whether capture can be accomplished in the window of time available to prevent an attack and without undue risk to civilians or to U.S. personnel. Given the nature of how terrorists act and where they tend to hide, it may not always be feasible to capture a United States citizen terrorist who presents an imminent threat of violent attack. In that case, our government has the clear authority to defend the United States with lethal force.

Of course, any such use of lethal force by the United States will comply with the four fundamental law of war principles governing the use of force. The principle of necessity requires that the target have definite military value. The principle of distinction requires that only lawful targets – such as combatants, civilians directly participating in hostilities, and military objectives – may be targeted intentionally. Under the principle of proportionality, the anticipated collateral damage must not be excessive in relation to the anticipated military advantage. Finally, the principle of humanity requires us to use weapons that will not inflict unnecessary suffering.

These principles do not forbid the use of stealth or technologically advanced weapons. In fact, the use of advanced weapons may help to ensure that the best intelligence is available for planning and carrying out operations, and that the risk of civilian casualties can be minimized or avoided altogether.

Some have argued that the President is required to get permission from a federal court before taking action against a United States citizen who is a senior operational leader of al Qaeda or associated forces. This is simply not accurate. “Due process” and “judicial process” are not one and the same, particularly when it comes to national security. The Constitution guarantees due process, not judicial process.

The conduct and management of national security operations are core functions of the Executive Branch, as courts have recognized throughout our history. Military and civilian officials must often make real-time decisions that balance the need to act, the existence of alternative options, the possibility of collateral damage, and other judgments – all of which depend on expertise and immediate access to information that only the Executive Branch may possess in real time. The Constitution’s guarantee of due process is ironclad, and it is essential – but, as a recent court decision makes clear, it does not require judicial approval before the President may use force abroad against a senior operational leader of a foreign terrorist organization with which the United States is at war – even if that individual happens to be a U.S. citizen.

That is not to say that the Executive Branch has – or should ever have – the ability to target any such individuals without robust oversight. Which is why, in keeping with the law and our constitutional system of checks and balances, the Executive Branch regularly informs the appropriate members of Congress about our counterterrorism activities, including the legal framework, and would of course follow the same practice where lethal force is used against United States citizens.

Now, these circumstances are sufficient under the Constitution for the United States to use lethal force against a U.S. citizen abroad – but it is important to note that the legal requirements I have described may not apply in every situation – such as operations that take place on traditional battlefields.

Stephen W. Preston, CIA General Counsel

April 10, 2012: Remarks at Harvard Law School

Suppose that the CIA is directed to engage in activities to influence conditions abroad, in which the hand of the U.S. Government is to remain hidden, – in other words covert action – and suppose that those activities may include the use of force, including lethal force. How would such a program be structured so as to ensure that it is entirely lawful? Approaches will, of course, vary depending on the circumstances – there is no single, cookie-cutter approach – but I conceive of the task in terms of a very simple matrix. First is the issue of whether there is legal authority to act in the first place. Second, there is the issue of compliance with the law in carrying out the action. For each of these issues, we would look first, and foremost, to U.S. law. But we would also look to international law principles. So envision a four-box matrix with “U.S. Law” and “International Law” across the top, and “Authority to Act” and “Compliance in Execution” down the side. With a thorough legal review directed at each of the four boxes, we would make certain that all potentially relevant law is properly considered in a systematic and comprehensive fashion.

Now, when I say “we,” I don’t mean to suggest that these judgments are confined to the Agency. To the contrary, as the authority for covert action is ultimately the President’s, and covert action programs are carried out by the Director and the Agency at and subject to the President’s direction, Agency counsel share their responsibilities with respect to any covert action with their counterparts at the National Security Council. When warranted by circumstances, we – CIA and NSC – may refer a legal issue to the Department of Justice. Or we may solicit input from our colleagues at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Department of State, or the Department of Defense, as appropriate. Getting back to my simple matrix …

Let’s start with the first box: Authority to Act under U.S. Law.

First, we would confirm that the contemplated activity is authorized by the President in the exercise of his powers under Article II of the U.S. Constitution, for example, the President’s responsibility as Chief Executive and Commander-in-Chief to protect the country from an imminent threat of violent attack. This would not be just a one-time check for legal authority at the outset. Our hypothetical program would be engineered so as to ensure that, through careful review and senior-level decision-making, each individual action is linked to the imminent threat justification.

A specific congressional authorization might also provide an independent basis for the use of force under U.S. law.

In addition, we would make sure that the contemplated activity is authorized by the President in accordance with the covert action procedures of the National Security Act of 1947, such that Congress is properly notified by means of a Presidential Finding.

Next we look at Authority to Act with reference to International Law Principles.

Here we need look no further than the inherent right of national self-defense, which is recognized by customary international law and, specifically, in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. Where, for example, the United States has already been attacked, and its adversary has repeatedly sought to attack since then and is actively plotting to attack again, then the United States is entitled as a matter of national self-defense to use force to disrupt and prevent future attacks.

The existence of an armed conflict might also provide an additional justification for the use of force under international law.

Let’s move on to Compliance in Execution under U.S. Law.

First, we would make sure all actions taken comply with the terms dictated by the President in the applicable Finding, which would likely contain specific limitations and conditions governing the use of force. We would also make sure all actions taken comply with any applicable Executive Order provisions, such as the prohibition against assassination in Twelve-Triple-Three. Beyond Presidential directives, the National Security Act of 1947 provides, quote, “[a] Finding may not authorize any action that would violate the Constitution or any statute of the United States.” This crucial provision would be strictly applied in carrying out our hypothetical program.

In addition, the Agency would have to discharge its obligation under the congressional notification provisions of the National Security Act to keep the intelligence oversight committees of Congress “fully and currently informed” of its activities. Picture a system of notifications and briefings – some verbal, others written; some periodic, others event-specific; some at a staff level, others for members.

John O. Brennan, Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism

April 30, 2012: “The Ethics and Efficacy of the President’s Counterterrorism Strategy”

So let me say it as simply as I can. Yes, in full accordance with the law—and in order to prevent terrorist attacks on the United States and to save American lives—the United States Government conducts targeted strikes against specific al-Qa’ida terrorists, sometimes using remotely piloted aircraft, often referred to publicly as drones. And I’m here today because President Obama has instructed us to be more open with the American people about these efforts.

Broadly speaking, the debate over strikes targeted at individual members of al-Qa’ida has centered on their legality, their ethics, the wisdom of using them, and the standards by which they are approved. With the remainder of my time today, I would like to address each of these in turn.

First, these targeted strikes are legal. Attorney General Holder, Harold Koh and Jeh Johnson have all addressed this question at length. To briefly recap, as a matter of domestic law, the Constitution empowers the President to protect the nation from any imminent threat of attack. The Authorization for Use of Military Force—the AUMF—passed by Congress after the September 11th attacks authorizes the president "to use all necessary and appropriate force" against those nations, organizations and individuals responsible for 9/11. There is nothing in the AUMF that restricts the use of military force against al-Qa’ida to Afghanistan.

As a matter of international law, the United States is in an armed conflict with al-Qa’ida, the Taliban, and associated forces, in response to the 9/11 attacks, and we may also use force consistent with our inherent right of national self-defense. There is nothing in international law that bans the use of remotely piloted aircraft for this purpose or that prohibits us from using lethal force against our enemies outside of an active battlefield, at least when the country involved consents or is unable or unwilling to take action against the threat.

Second, targeted strikes are ethical. Without question, the ability to target a specific individual—from hundreds or thousands of miles away—raises profound questions. Here, I think it’s useful to consider such strikes against the basic principles of the law of war that govern the use of force.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store