The (No Longer) Almighty Soybean

More on:

The U.S. trade deficit rose in October.

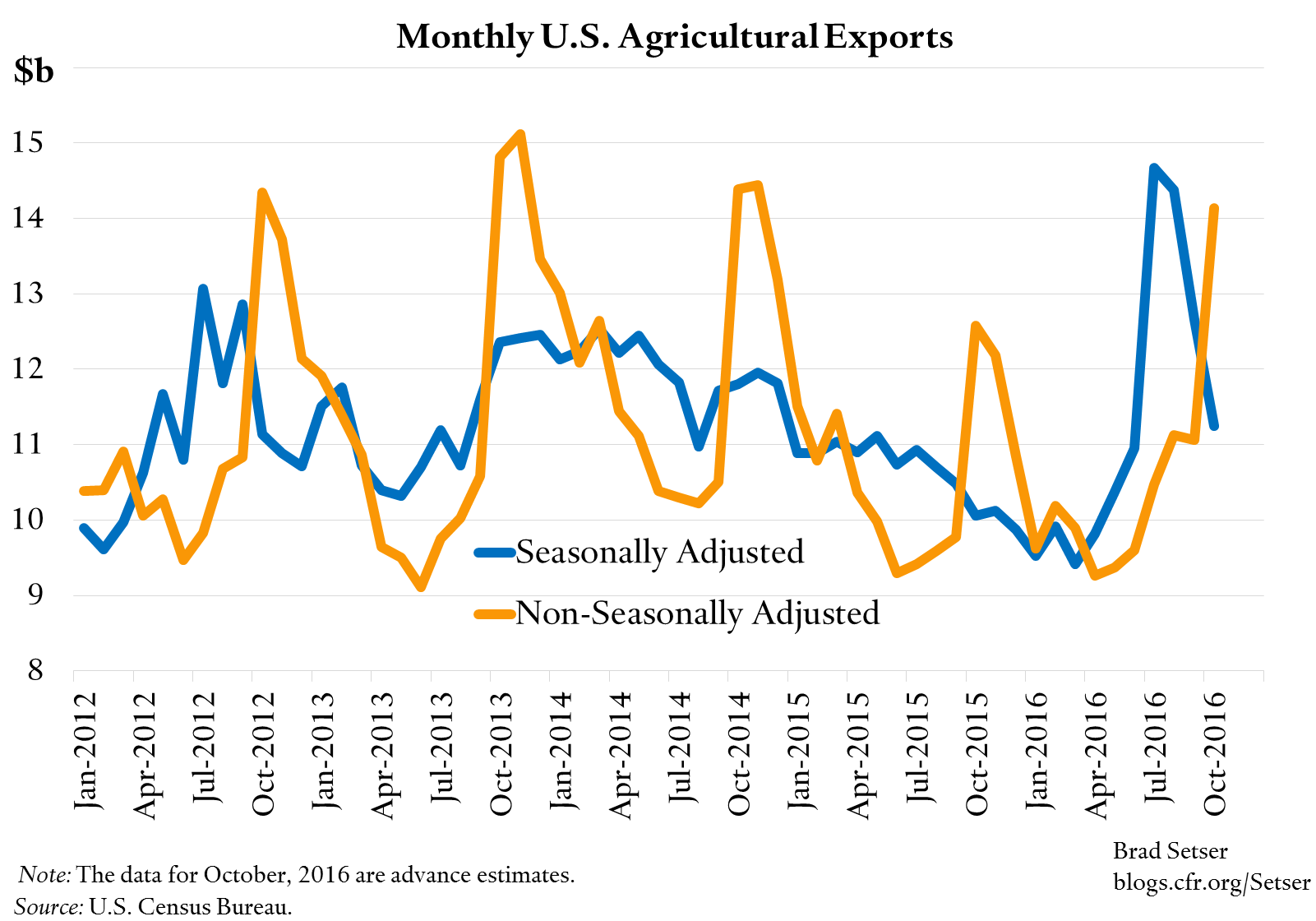

One reason (no surprise): Soybeans. Seasonally adjusted, monthly soybean exports are now $3 billion off their July and August peak. Actual soybean exports—in billions of dollars—rose in October. As they should. Soybeans have real seasonality: U.S. exports peak after the harvest. The seasonal adjustment seeks to smooth out this natural month-to-month volatility.

The good news from the summer is now mostly behind us. Still, as a result of the out of season exports—and higher prices—the U.S. has already exported $7.5 billion more soybeans this year than last.

I want to highlight two other points, both of which are—I fear—a sign of things to come. What I suspect is the beginning of a sustained—though modest by past standards—rise in the petrol deficit, and, more concerning, the growing U.S. deficit in high-end capital goods.

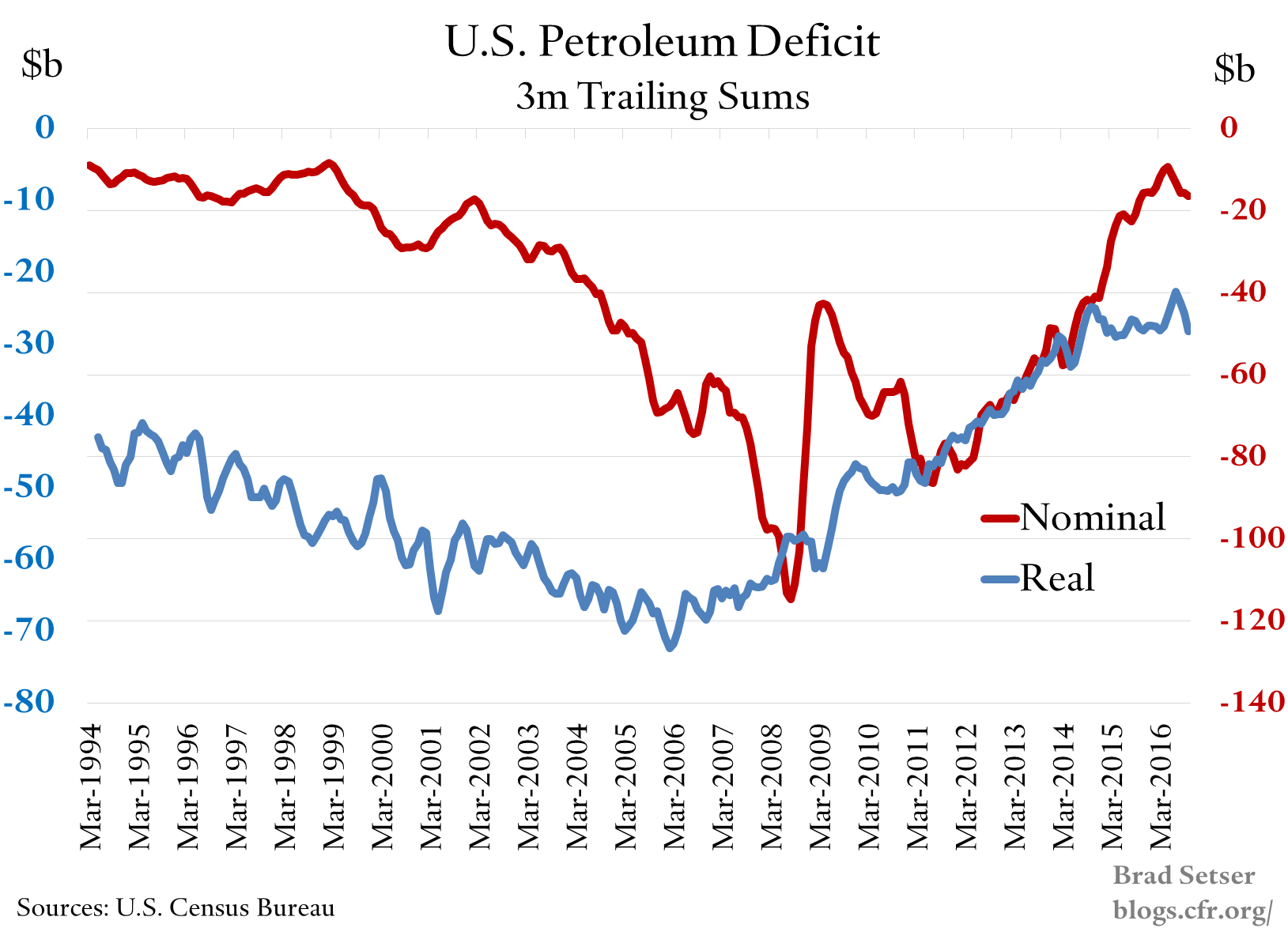

I will not try to replicate Calculated Risk’s always excellent graphs. There is no doubt that the nominal petrol deficit has started to tick up, after big falls for several years (in nominal terms, the non-petrol deficit is back to where it was before the crisis, a shift that hasn’t gotten the attention it deserved).

In real (volume) terms, the U.S. petrol deficit is also starting to rise. The large tailwind that rising oil production, falling oil imports, and falling prices provided for the the overall U.S. balance of payments in the past few years is in the process of turning into a modest headwind.

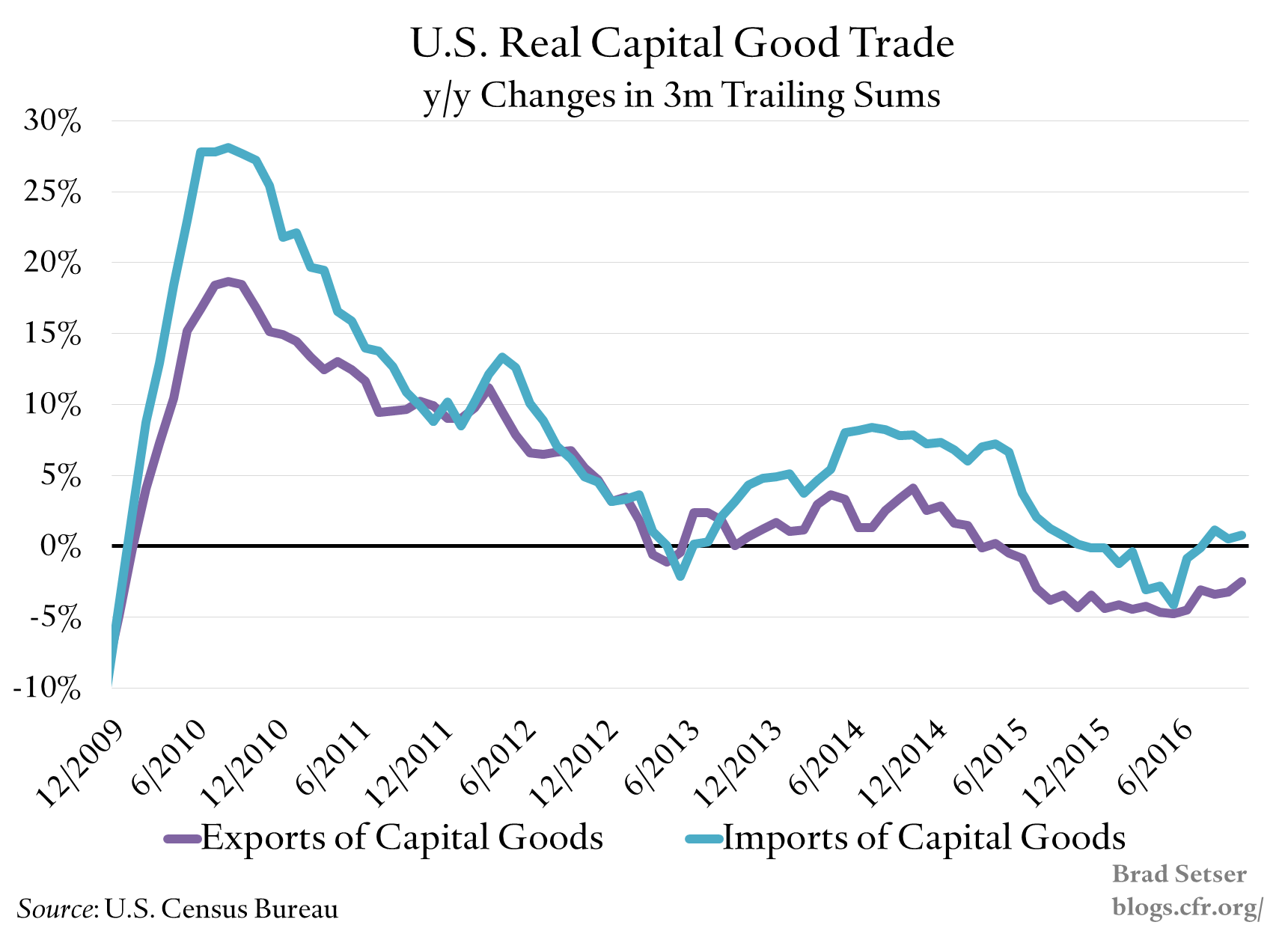

More concerning, though, is the current weakness in U.S. capital goods exports. Capital goods are the complex big ticket items where advanced, technically sophisticated economies are supposed to excel. Aircraft, turbines, semiconductors, oil drilling equipment, telecommunications switching equipment, and the like. The U.S. now runs a deficit in capital goods—$60 billion in the first ten months of the year, which projects out to $70 billion for the full year.

U.S. imports of capital goods also now exceed U.S. imports of consumer goods (data here, exhibits 6, 7 and 8). That is sometimes lost in the coverage of trade issues; the U.S. deficit right now isn’t all iPhones and other consumer goods.

Nominal capital goods exports are down around $20 billion year to date (aircraft engines and semi-conductors are up, but almost every other category is down—with the biggest falls in categories linked to oil drilling and mining). Nominal imports are also down, but by less.

Real capital goods exports are down 3.5 percent year over year (and 2.5 percent in the last three months of data; October actually had a somewhat smaller fall). They have been held back by the global fall in capital investment in drilling and mining, and by the impact of the strong dollar. The current fall in exports maps closely to projections based on the Fed’s trade model.

Real capital goods imports are down 1 percent year over year (and are up modestly in the last three months of data). The weakness in capital goods imports earlier in the year likely reflects the broader fall off in investment in mining and drilling that followed the commodity price correction in 2014. A growing economy would—under normal circumstances—lead this to rise.

There though is still one part of the trade data that is a bit puzzling. Real consumer goods imports are down a bit over 2 percent for the year, and 4.5 percent in the last three months of data (August and September were especially weak). While inventory adjustments can create gaps between imports and domestic demand, those gaps tend not to last forever —I would expect consumer goods imports to start to pick over the next few quarters.

I am often surprised that the extent of the recent slowdown in U.S. exports is not more widely known. There is no question that manufactured exports have taken a hit after the dollar’s rise. As Bill Cline of the Peterson Institute makes clear, there is every reason to expect further weakness at the dollar’s current level.

October’s rising trade deficit is thus likely a sign of things to come. The impact of oil price changes on U.S. imports and the impact of dollar on the U.S. exports are known knowns, so to speak. And it is likely—barring a major policy shift from President-Elect Trump—that real imports will start to rise again soon, especially if U.S. demand gets a bit of additional support from tax cuts next year.*

* Nominal imports are more complicated. The rise in the dollar in November should bring down import prices a bit. Certainly over the past few years import prices have fallen significantly while the price of U.S. made goods has continued to rise. That is the irony of the Trump era: barring a rise in tariffs, there are plenty of incentives to import more (whether components for a final product, or the final product itself).

More on:

Online Store

Online Store