Race, Gender, Region: Understanding the Decline in U.S. Life Expectancy

This is a guest post by Thomas J. Bollyky, senior fellow for global health, economics, and development at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Last week, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, released its 2015 mortality statistics, which showed U.S. life expectancy fell from 78.9 to 78.8 years over the prior year. This means roughly 86,000 more deaths last year in the United States than in 2014, a 1.2 percent jump in the U.S. death rate. These startling results generated substantial media attention, building on the election-year narrative of the declining fortunes of Americans, especially working class white men.

More on:

As the chief of the Mortality Statistics Branch at the NCHS has pointed out, no one really knows what led to the downward turn in U.S. mortality in 2015 or if that trend will continue (the preliminary results from 2016 apparently suggest otherwise). So it is worth putting these results in the context of long-term trends in U.S. life expectancy and comparing them to other nations. Three lessons emerge when you do.

1. U.S. life expectancy hasn’t gotten worse as much as it stopped getting better

Death rates have been declining for decades in the United States as a result of improvements in health care, disease management, and medical technology. A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that between 1969 and 2013, U.S. death rates fell 43 percent with declines in the mortality rates for the following ailments: 77 percent for stroke; 68 percent for heart disease; 18 percent for cancers; and 17 percent for diabetes. But the study also found those gains were not spread evenly throughout that 44-year period and had slowed dramatically in recent years.

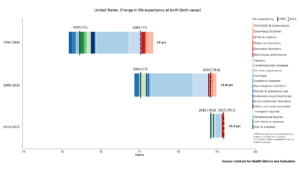

More recent data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), shown in the figure below, demonstrate how the changes in U.S. life expectancy since 2010 differ from the previous two decades and the contribution that different diseases have made to that change. The improvement in U.S. life expectancy was roughly two years in each of the previous two decades. The reason for that improvement was that the significant declines in U.S. mortality rates for cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and HIV/AIDS exceeded the more modest rise in the death rates for diabetes, substance abuse, and those associated with mental illnesses.

Since 2010, the gains in U.S. life expectancy have been a more modest 0.3 years. There have been no increases in the mortality rates of major diseases over the last five years that have been big enough to affect life expectancy nationally, but the large improvements in cardiovascular and cancer rates have tapered off. One theory, advanced by David Cutler, is that previous improvements in U.S. life expectancy were driven by more people taking the current generation of lifesaving medicines like statins for high cholesterol levels. But that effect may have reached its limit. Without new treatments and still too few Americans adopting healthier lifestyles, the improvement in U.S. life expectancy has ground to a near halt.

More on:

2. The United States has fallen behind its peers, but that shortfall is not new

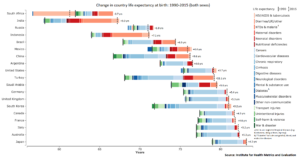

The United States is not alone in experiencing more modest gains in life expectancy rates in recent years. According to IHME data, Australia and Italy have likewise added only 0.3 years to their average life expectancy since 2010 and the gains in Japan, France, and Canada have not been much better (0.4-0.5 years) over that time.

The difference is that these other nations already had longer average life expectancies than the United States and enjoyed greater improvements in their mortality rates over the last two decades. This is particularly true for cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in most wealthy countries. The declining death rates for cardiovascular disease in other wealthy nations far outpaced the improvements enjoyed by Americans.

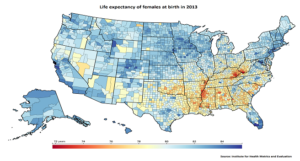

3. Region, not race and women more than men

Many of the factors behind the difference in the life expectancy of Americans relative to their peers in other wealthy countries are well-known. Despite spending the highest amount of any nation on healthcare, the United States has, as demonstrated in the figure below, staggering and growing disparities in life expectancy. Those disparities are now greater across regions than between races. In the highest-performing regions, life expectancy rivals countries with the highest life expectancy in the world, such as Switzerland and Japan. But the life expectancy in the lowest-performing regions, particularly in parts of the Southeastern United States, is lower than it is in Bangladesh.

For all the recent focus on men, it is women in half of the counties in the United States who have experienced no real gains in life expectancy since 1985. The same is true for men in only 3 percent of U.S. counties.

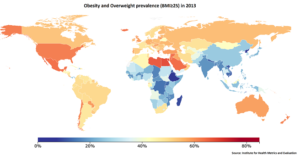

Thousands of lives could be saved in the United States, especially among women, with healthier diets, higher levels of physical activity, and better blood pressure management. The United States is devoting more resources to tackling these concerns and, while U.S. obesity rates remain among the highest in the world, the rate of increases has slowed in recent years.

The same cannot be said internationally, however. The United States is an early adopter of unhealthy diet and lifestyles, but it is not alone. Obesity rates in Mexico match those in the United States and, as the figure below shows, are rising throughout Latin America, North Africa, and the Middle East.

As poor diets and unhealthy lifestyles spread to poorer nations without the same health care resources as the United States, rates of cardiovascular and other chronic diseases are increasing much faster in much younger populations than in the United States.

Change is afoot, with the expected repeal of the Affordable Care Act and the future of international aid programs uncertain in the incoming Trump administration. The trends underlying stagnating U.S. life expectancy rates are cause for concern and a signal to guide future investment. We should listen and act accordingly to redress U.S. regional health disparities, facilitate better lifestyle choices, and confront the rising threats to global health.

Online Store

Online Store