Should the US worry about the drop in foreign demand for US long-term assets?

More on:

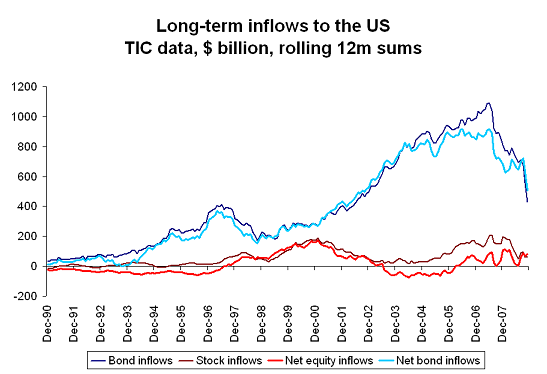

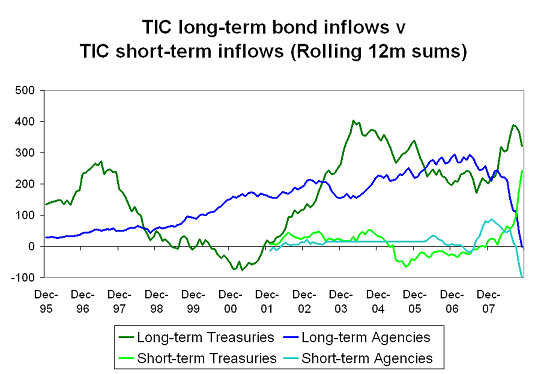

The latest TIC data provides yet more evidence that financial globalization -- the rise in cross-border flows -- has peaked. At least temporarily. Foreigners are buying far fewer long-term US bonds than they used too.

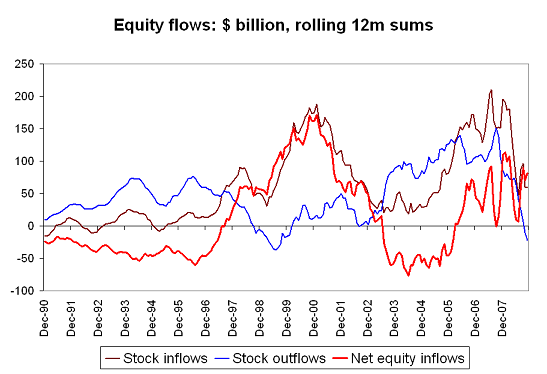

Look at a plot of gross foreign purchases of US long-term bonds and gross foreign purchases of US equities. Both are heading down. Net long-term bond flows are heading down too. Net equities aren’t heading down, but (see below) that is largely because Americans are now selling their foreign equity portfolio faster than foreigners are selling their US equities.

It is also striking, at least to me, that bond inflows have been so much larger than equity inflows over the past few years. Popular coverage of the "markets" in the US focuses on the equity market. But the capacity of the US to sustain its low savings rate hinged not on foreign demand for US equity but rather foreign demand for US bonds. Apart from a brief period around the .com craze, the US never financed its external deficit by selling equity to the world.

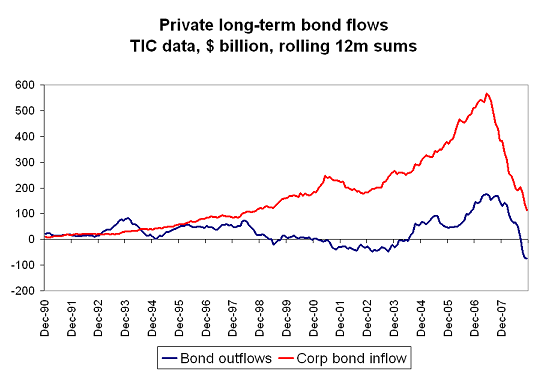

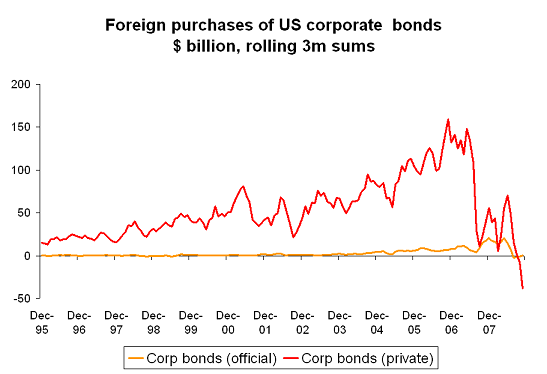

What is driving the fall in demand for long-term US bonds? Number one, a fall in demand for corporate bonds. Remember that all "private" mortgage backed securities are considered corporate bonds in the balance of payments data. Private US demand for foreign bonds is also falling.

The fall in demand for corporate bonds over the last three months has been quite sharp -- comparable to the fall in the three months after the August subprime crisis. Then again, there is no need to look at the balance of payments data to know that things are bad.

But a second factor is now also at play. Central bank demand for long-term bonds is falling. Right now that is largely because central banks are shifting (rather dramatically) into short-term bills. But the fall in the pace of reserve growth implies that the overall pace of central bank purchases of both short and long-term US debt should eventually slow.

Over the past 12 months, central bank purchases of t-bills have exceeded total foreign purchases of equities by a factor of about four. Foreign purchases of long-term Treasuries (mostly from central banks) exceeded foreign purchases of equities by a factor of between five and six. And total foreign demand for Treasuries exceeded foreign demand for US equities by a factor of about ten.

If the US weren’t the US, I suspect analysts would now be worried about a fall in the quality of financing for the US external deficit. The US external deficit is increasingly financed at the short-end of the curve (usually a danger sign) and by the sale of the United States existing portfolio of external assets, not by the sale of long-term debt.

But the financing of the US deficit always has been a bit strange. The big surge in demand for US debt afterall corresponded with a weak dollar, not a strong dollar. It reflected a world where private capital was flowing into the emerging world, financing enormous reserve growth that fed back into enormous central bank demand for US debt. It that sense it wasn’t ever a sign of true strength.

And the surge in foreign demand for corporate bonds after 2004 clearly reflected the expansion of the shadow banking system. American money market funds bought short-term paper issued by various "vehicles" in Europe (and especially the UK) that bought long-term US debt. This flow reflected the need for institutions who borrowed short and lend long to take credit risk when the yield curve flattened as much as anything else. That intermediation just happened to be structured in a way that generated large cross-border flows. It didn’t, it turns out provide much net financing. That is why -- at least in my view - the collapse of European demand for US corporate bonds didn’t force an immediate correction in the current account deficit.

Conversely, the surge in short-term inflows to the US coincided with the dollar’s recent rally. That in some sense is the puzzle. In the past, record demand for US financial assets was strangely enough tied to dollar weakness. And now a deterioration in the quality of the inflows is tied to dollar strength. Go figure.

Still, it is hard to be too worried about this shift so long as the dollar remains strong. Too strong actually. In the long-run, as Martin Wolf rightly notes, the US needs to be able to rely at least in part on net exports for growth. The dollar’s recent rally makes that harder.

Moreover, the current account deficit is going down not up, largely because of the fall in oil prices. That -- together with the world economy’s broad-based weakness -- seems to mitigate against a near-term dollar crisis. No one right now wants to see their currency appreciate. Not when exports are falling across the board.

At the same time, it is risky to finance a large external deficit with short-term debt. Even for the US. If the US deficit starts to head back up again -- as, for example, the effect of the recent fall in oil prices wears off and a large fiscal stimulus in the US stimulates the world economy -- without a shift in the composition of inflows, there would be cause for concern.

That just highlights a bigger issue, one that I don’t think has been settled: How will the world’s remaining current account deficits be financed in the post-crisis world? Right now, they are in some sense being financed by the unwinding of all the pre-crisis bets. And by running down existing stocks of foreign assets. But that process cannot last forever ...

More on:

Online Store

Online Store