Splitting out Emerging Economies Changes the Picture on Global Trade

More on:

The Financial Times’ Big Read feature on hidden trade barriers included a chart showing the growth in trade relative to the growth of the world economy. The graph showed, accurately, that trade is now growing a bit more slowly than the world economy.

The question is why.

A relatively simple adjustment helps answer the question.

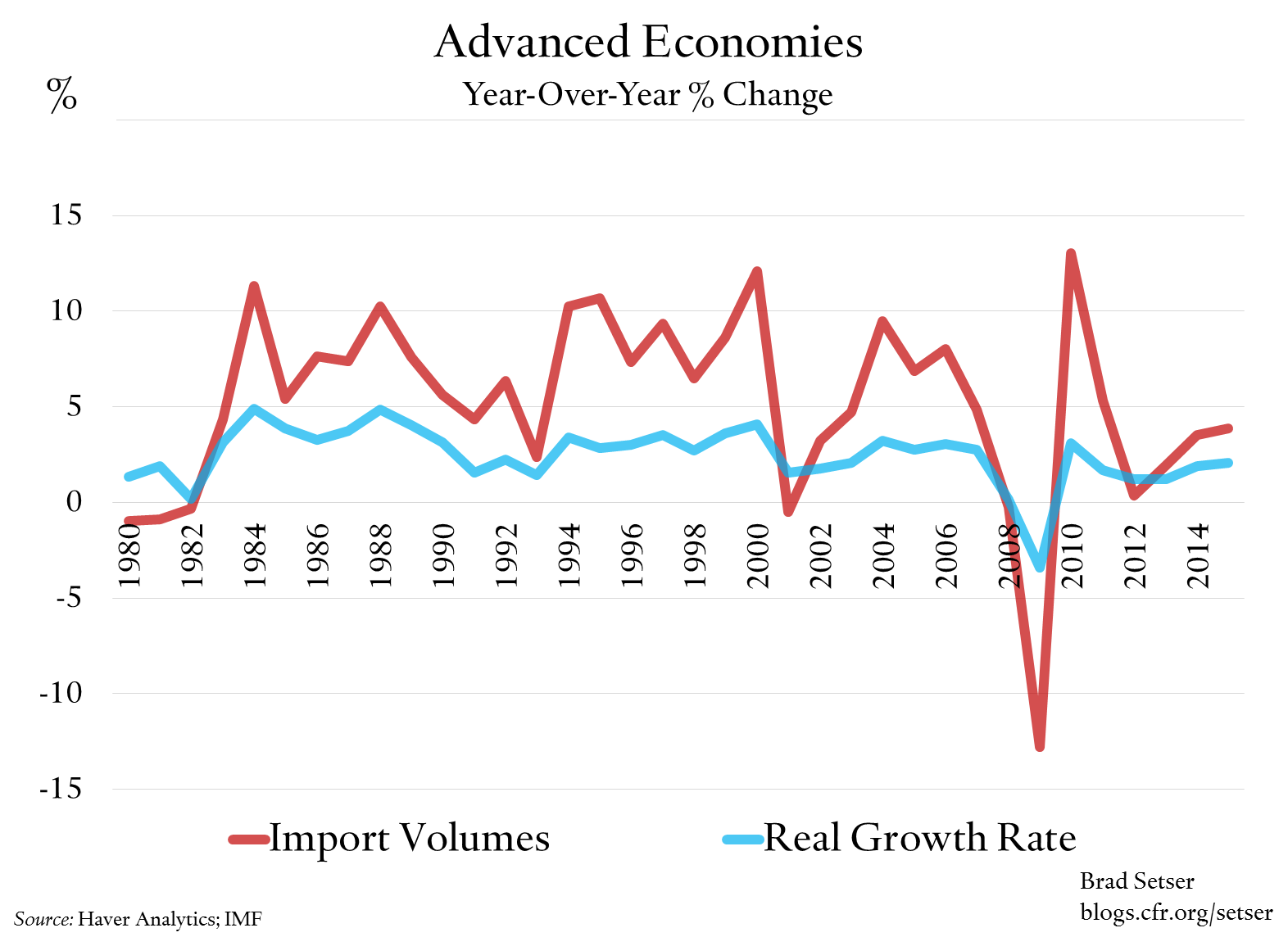

Look at a plot of import growth (goods only in this graph, but it doesn’t change if you use goods and services) against growth in the advanced economies, using the IMF’s WEO data set.

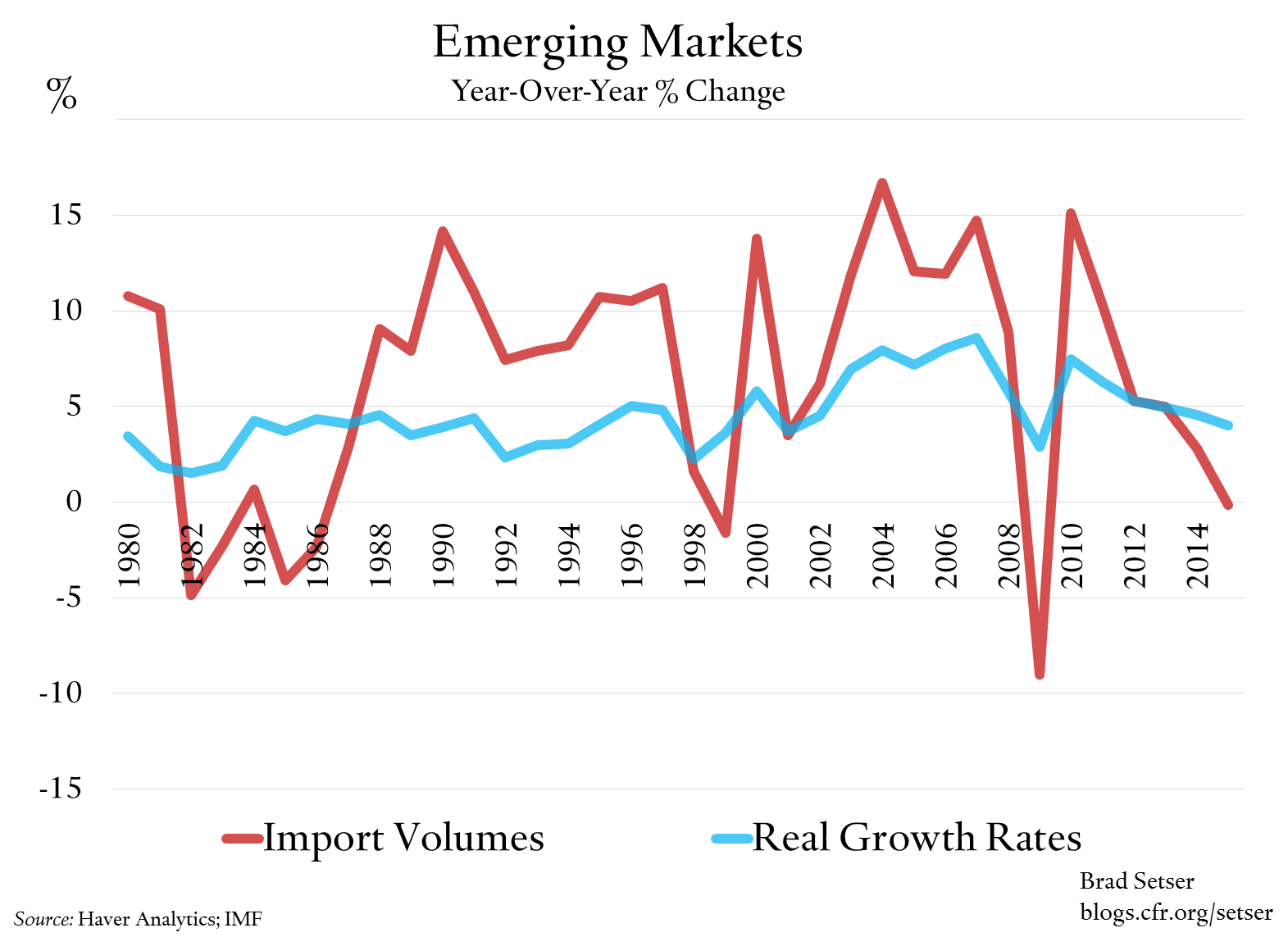

And now consider the same plot for the emerging economies.

Eyeball economics tells us that import growth has really slowed in the emerging economies, both absolutely and relative to growth. 2015 emerging market import growth sort of look like 1998, and that wasn’t a good year for the emerging world. Advanced economy imports by contrast grew a bit faster than overall growth. Much more sophisticated economics tells a similar story.

Europe is actually pulling its weight here. Eurozone imports have picked up along with the modest revival in eurozone demand over the last couple of years. The problem in the eurozone is that the demand recovery has been weak more than anything else.

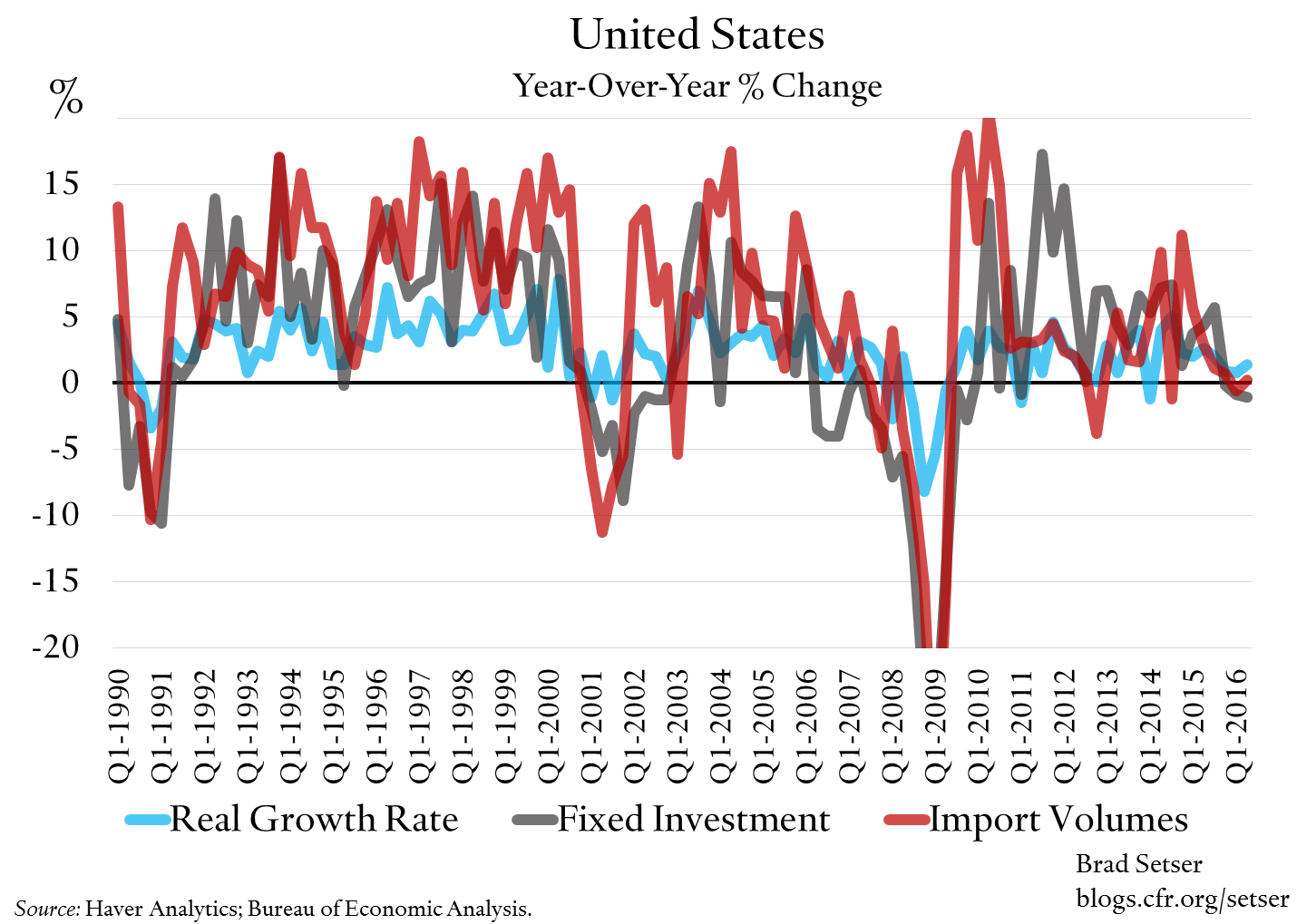

In the U.S. non-oil imports were rising at a decent clip in 2013 and 2014. Since then, import growth has slowed—in part because of high levels of inventories, and in part because of the slowdown in investment. Goldman’s U.S. economics team recently estimated that the investment slump accounts for about half of the slowdown in U.S. imports. And a large part of the fall in investment in the U.S.—as in the emerging economies—is tied to the fall in commodity prices.

The policy lessons here are clear enough.

There are the risks associated with a potential sharp turn inward in the advanced economies.

But the emerging economies shouldn’t be let off the hook. Even after taking into account the fall in investment and the associated fall in demand, emerging market imports have been a bit on the soft side (see the IMF WEO chapter on trade for example).

Some of that is the introduction of new, hidden barriers to new kinds of trade, as Shawn Donnan and Lucy Hornby of the FT emphasized. But there are also a lot of old-fashioned, tax-at-the-border barriers to trade in many emerging economies. Over time China’s industrial policy has focused less on export promotion and more on import substitution. I suspect that we are now starting to see the result.

I also take seriously the argument that the acceleration in trade in the ’90s and ’00s may be the exception, not the rule—though I would still expect some recovery in trade as investment normalizes after the 2014-15 commodity shock.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store