TWE Remembers: JFK Fakes a Cold (Cuban Missile Crisis, Day Five)

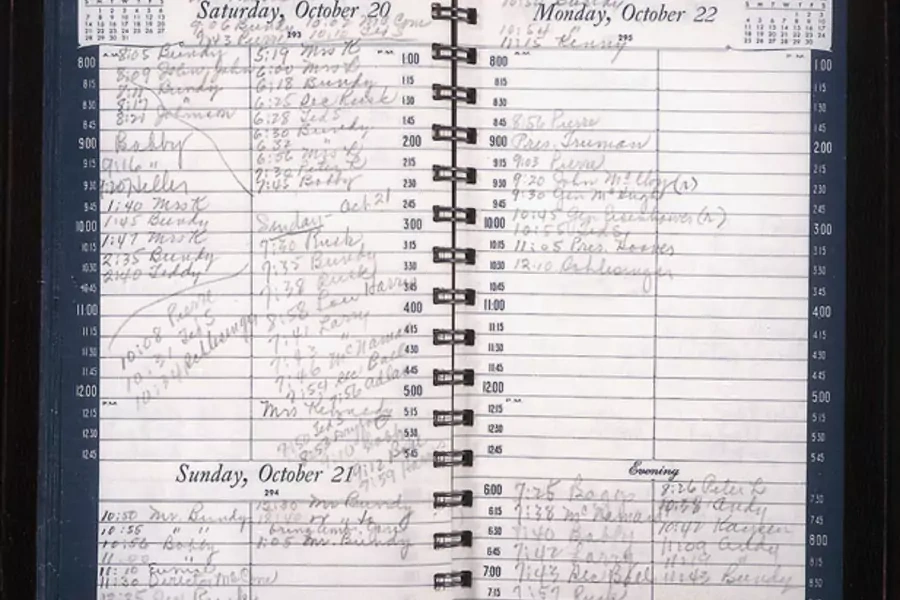

Have you ever faked an illness to get out of a meeting or to avoid an obligation? President John F. Kennedy can do you one better. He faked a cold on Saturday, October 20, the fifth day of the Cuban missile crisis, so he could cancel a campaign tour in the Midwest and return to the White House to meet with his national security team about the U.S. response to the Soviet missiles in Cuba.

Kennedy woke up on October 20 in the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago, where he had given a speech at a Democratic Party fundraiser the night before. At 10 a.m., his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, called to say that the ExCom was ready to discuss response options with him. Half an hour later, Kennedy’s staff began informing the press and the hosts for the day’s scheduled campaign events that he was running a fever and would be returning to Washington on his doctor’s orders.

More on:

Kennedy arrived back at the White House a little after 1:30 p.m. He immediately went for a swim. Robert Kennedy sat poolside. The two men chatted when the president took breaks from his laps.

The ExCom meeting began at 2:30 p.m. and ran for more than two-and-a-half hours. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara made the case for imposing a blockade on Cuba. It would cause the United States “the least trouble” with its allies, avoid a surprise attack that would be “contrary to our tradition,” be compatible with America’s “position as a leader of the free world,” and be less likely to “provoke a response from the USSR which could result in actions leading to general war.” McNamara admitted that the blockade was not a perfect option. It might take a long time to compel the Soviets to withdraw the missiles from Cuba, “it would result in serious political trouble in the United States,” and “the world position of the United States might appear to be weakening.” There was one other disadvantage to the blockade that the president pointed out: it would allow the Soviets to continue installing missiles with whatever materials were already in Cuba, thereby allowing the threat to the United States to increase.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Maxwell Taylor and National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy pressed the case for an air strike, which was nicknamed the Bundy plan. Taylor’s principal argument was that time was not on the U.S. side. More missiles would become operational with each passing day, and the Soviets would have time to hide launch sites, reducing the effectiveness of a preemptive strike. McNamara countered that the air strike would miss some missile sites in any event, leaving the United States vulnerable to a counterattack. Moreover, Taylor’s preferred plan would target far more than just missile launch pads, and in doing so, kill thousands of Soviet soldiers. Moscow would likely retaliate, though not necessarily in Cuba. The United States could not assume that it could control events after that.

As the meeting continued, Kennedy and his advisers discussed variations on the two main proposals, including a hybrid version floated by Robert Kennedy in which a blockade would be imposed as a first step to be followed by an air strike if necessary. CIA director John McCone pointed out that U.S. intelligence did not know for certain whether the nuclear warheads that would eventually be matched to the Soviet missiles had already arrived in Cuba. All that was certain was that work had begun on the storage sheds for the warheads.

Kennedy and his advisers also discussed whether the United States should offer carrots to entice Moscow to withdraw the missiles. Both McNamara and UN ambassador Adlai Stevenson raised the possibility of offering to withdraw U.S. missiles from Turkey and either leaving or limiting the use of the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay. Kennedy dismissed the idea of retreating on Guantánamo as conveying U.S. weakness, but he left open the door to withdrawing U.S. missiles from Turkey.

More on:

After hearing from his advisers, Kennedy hedged his bets. He told his advisers to proceed with the blockade. But he also directed his national security team to take the steps necessary to give him the option of ordering an air strike against Soviet missile installations in Cuba within forty-eight to seventy-two hours. Kennedy also directed his chief speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, to draft a speech that he would give to the nation on Monday night.

The world would soon learn that Kennedy had fibbed about his fever. The reason for his sudden departure from Chicago was far graver than the common cold.

For other posts in this series or more information on the Cuban missile crisis, click here.

Online Store

Online Store