More on:

Next week, Aung San Suu Kyi and a host of other dignitaries, including United Nations Secretary General Ban ki-Moon, will preside over a major peace conference in Naypyidaw. The conference is billed as a kind of sequel to the Panglong conference, held in February 1947, and presided over by Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, Aung San. At the original Panglong, Aung San, then essentially interim head of the government, and many ethnic minority leaders agreed to work together in a national government. The agreement they made was supposed to create a kind of federal state, though leaders from several large minority groups did not participate at Panglong. The deal essentially fell apart anyway, as Aung San was assassinated, and Myanmar drifted into civil war and then, eventually, military rule. The idea of a truly federal and effective state would have to wait.

Aung San Suu Kyi hopes that next week’s conference will begin to do what her father’s could not, putting Myanmar on the road to a real, nationwide peace and setting the stage for a new conception of the country, which might include redrawing some of the borders of Myanmar’s states. Since independence, the country has never really enjoyed national peace, and a truly sustainable, nationwide peace agreement would be one of the most remarkable achievements in modern Asian history. It also would pave the way for significant investment in areas of the north and east of Myanmar that have been home to insurgencies for decades. The peace conference also could send a clear message, to all Myanmar citizens, that only a more decentralized, federal form of government will work in such an ethnically and religiously diverse country. Although other countries in Southeast Asia, like Indonesia, have embraced political and economic decentralization, it has always been a hard sell to many Burmans, and to some ethnic minorities who feel that accepting even some degree of a rule from Naypyidaw will result in their areas becoming increasingly Burmanized.

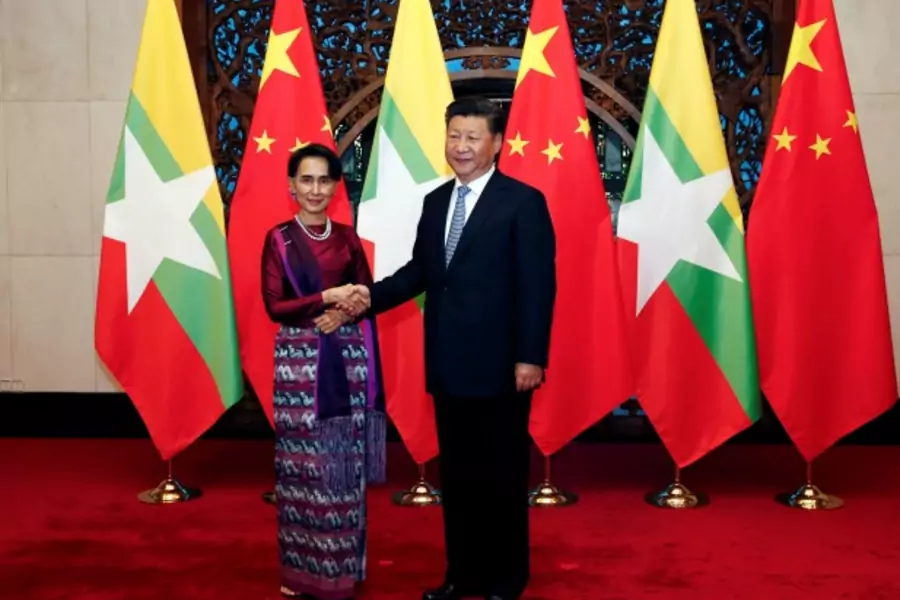

There are some very positive signs for the meeting next week, which is officially called the Union Peace Conference, but is also known as the 21st Century Panglong Conference. During her visit to China last week, Aung San Suu Kyi got a public commitment from Beijing to support the peace talks, including a not-so-subtle signal that holdout insurgent groups---those that have not signed a previous cease fire---should participate. China has substantial leverage over some of these holdouts. During the Aung San Suu Kyi visit to China, three of the holdout groups with close links to China released a letter saying that they will attend the Union Peace Conference. A meeting between Aung San Suu Kyi and the head of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank also was a signal that Beijing hopes to play a role as peace-maker in Myanmar, and then potentially push infrastructure development links between southwestern China and northern Myanmar.

Indeed, it is highly possible that some of the eight holdout groups will sign a national ceasefire agreement next week. Several Myanmar officials have suggested that the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), one of the two biggest and most heavily armed holdouts, will sign next week. This seems overly optimistic, although many reports suggest that the KIO’s preparatory meetings with government officials have been positive, with progress being made. And the UN Secretary General’s attendance at the conference is an important signal of how the international community strongly backs a peace deal.

In addition, it appears that senior Myanmar military leaders have decided to strongly back the 21st Century Panglong Conference idea. That the armed forces would want peace might seem intuitive. Yet continuing insurgencies provided a rationale for decades of military rule, and also for the armed forces to remain closely involved in politics even as the country began its transition to civilian government in the early 2010s. So, it was not a cinch that top military leaders would necessarily support a peace conference. And some regional commanders indeed may not support the peace talks; Myanmar army units this week reportedly have been launching aerial attacks on Kachin Independence Army positions, not exactly conveying a message of peace.

But Aung San Suu Kyi and the government still will have major hurdles toward a real national peace. Most important, what will become of the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the largest and by far most militarily powerful ethnic insurgent group? Wa leaders have expressed their support for the conference, and it appears that Wa representatives will attend the conference. This is an important signal from an insurgent group that probably cannot be defeated militarily. Still, what deal could satisfy Wa leaders and the people of UWSA-held territory, who have been used to a kind of de facto independence for decades? Perhaps the recognition of a Wa State, as one of the states in a federal Myanmar, would be enough to satisfy many ethnic Wa. The peace conference negotiations indeed could produce the outlines of a future Wa State, which would then be hammered out in the follow up talks that are supposed to be held every few months after the initial conference.

But Wa leaders have built massive fortunes, allegedly through narcotrafficking. Even with a high degree of autonomy, would a Wa State no longer actually run by the UWSA be able to continue its massive illegal activities? Wa regions could become important trading hubs, but licit trade alone would not make up for the loss of revenues if the UWSA disarmed and gave up narcotrafficking. The Wa regions do not have the natural resources, like timber or copper, which other ethnic minority areas possess.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store