What Would Trump Do if There Were Another Tiananmen Incident?

Margaret K. Lewis is a professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law and a Fulbright research fellow at National Taiwan University School of Law.

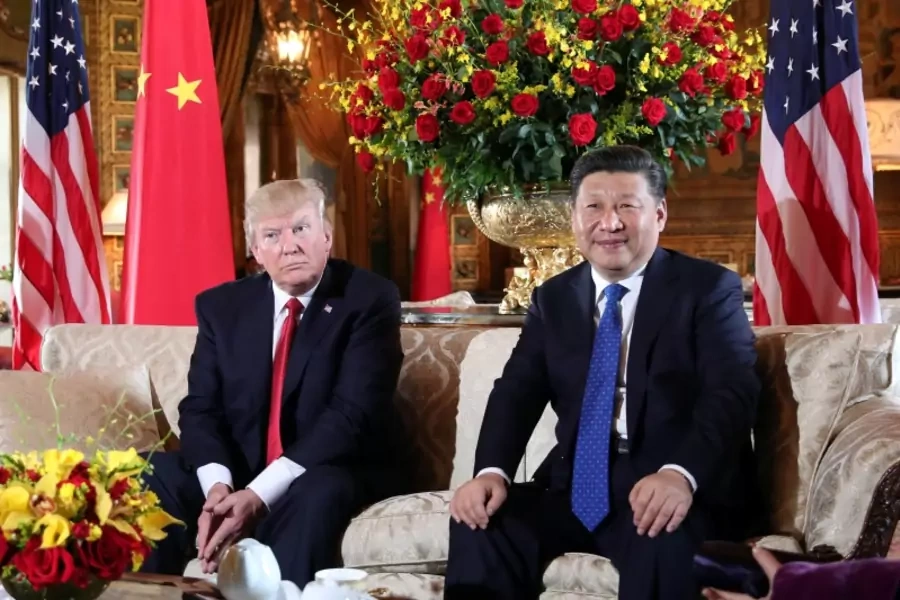

As the world reflects on this week’s anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests and subsequent violent crackdown by the PRC government, it is worth contemplating what President Donald J. Trump would do if faced with a similar situation. When asked about Tiananmen during the campaign, Trump said he was not “endorsing” China’s response, but he called the demonstrations a “riot.” Would President Trump see a riot or a massacre if the events of June 4, 1989, were replayed today?

More on:

The U.S. bombing raid in April that President Trump linked to the Syrian government’s use of chemical weapons against civilians suggested that human rights would be prominent in shaping foreign policy. Yet President Trump’s remarks during his recent visit to Saudi Arabia and praise for leaders with deeply problematic human rights records, such as Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, caution otherwise.

Specifically regarding China, in March 2016 the Obama administration joined eleven other countries in issuing a rare statement expressing “concern[ ] about China’s deteriorating human rights record” and calling on China “to uphold its laws and its international commitments.” The United States was noticeably absent a year later when eleven countries—including Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom—sent a letter to the Chinese government expressing “growing concern over recent claims of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment in cases concerning detained human rights lawyers and other human rights defenders.”

The Trump administration is admittedly not breaking the mold: U.S. government policy towards China has always been, at least to some degree, pragmatic. President Jimmy Carter entered office with human rights as a cornerstone of his foreign policy. Nonetheless, even he recognized the United States’ many interests when dealing with China and normalized relations. President George H. W. Bush suspended military contracts and technology exchanges with China following the Tiananmen Square massacre. President Bill Clinton, however, restored China’s most favored nation trading status four years later and quickly relaxed rhetoric that China must make significant progress towards conforming with international human rights standards.

While the tension between principles and pragmatism is not new in U.S. policy towards China, the current dismissive attitude towards human rights is jarring. The past four months indicate that policy decisions based on immediate economic and security calculations will prevail over long-held human rights values. As I have argued elsewhere, this is a mistake. Addressing human rights in both a principled and pragmatic way requires not just stating that human rights matter in the abstract but also articulating an integrated, executive-branch-wide plan for how human rights will be raised in various contexts.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson opened the door for such an approach in his April 7, 2017, briefing when a dedicated human rights dialogue was conspicuously absent from the announced list of bilateral dialogues. When asked whether the United States would pressure China on human rights violations, Secretary Tillerson responded that he did not think there needed to be a separate conversation on human rights because “[t]hey’re really embedded in every discussion, that [ ] is really what guides much of our view around how we’re going to work together.” What remains to be seen as the revamped dialogues take shape is whether human rights will be embedded in the sense of integral or, in contrast, embedded in the sense of hidden like an unseen fossil encased in stone. Will freedom of expression be a central component of discussions regarding cybersecurity? And will protections for the accused be at the forefront of conversations regarding repatriating fugitives as part of bilateral law enforcement efforts?

More on:

Admittedly, even if President Trump raises the priority of human rights on the bilateral agenda, it would not be a panacea. Chinese President Xi Jinping has rebuffed foreign pressure, including a scathing rebuke by the UN Committee Against Torture as part of the PRC’s periodic review of its implementation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

PRC government intransigence is, however, not reason to throw in the towel. First, U.S. government involvement can be critical in specific cases. The Trump administration deserves kudos for facilitating the return of American citizen Sandy Phan-Gillis after her prolonged arbitrary detention by the PRC government. Second, condemnation of human rights abuses can help hearten people in China who have seen their rights, as well as those of friends and family, violated. Third, beyond individual cases, building interpersonal ties by engaging Chinese officials and members of civil society in conversations regarding human rights lays the groundwork for more substantive long-term cooperation after the current political winds shift, whenever that may be. Finally, taking a principled stance on human rights signals to the world that the United States is indeed standing behind core human rights values as we struggle to regain our moral authority in the wake of glaring abuses committed as part of the “war on terror.”

Let us hope that President Trump will not confront a tragedy on the scale of 1989. But the Trump administration must grapple with the ongoing human rights violations in China. In doing so, it should not let its acts be driven by pragmatism at the expense of principles. As exhorted by Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei, “Your own acts tell the world who you are and what kind of society you think it should be.”

Online Store

Online Store