Who Governs Global Value Chains?

More on:

Global trade and the supply chains that support it are undergoing a period of profound change. Supply chains face threats including a resurgence of protectionism, climate change, decaying infrastructure, and human rights abuses. The Development Channel’s series on global supply chains will highlight experts’ analysis on emerging trends and challenges. This post is from Dr. Sherry Stephenson, senior fellow at the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD).

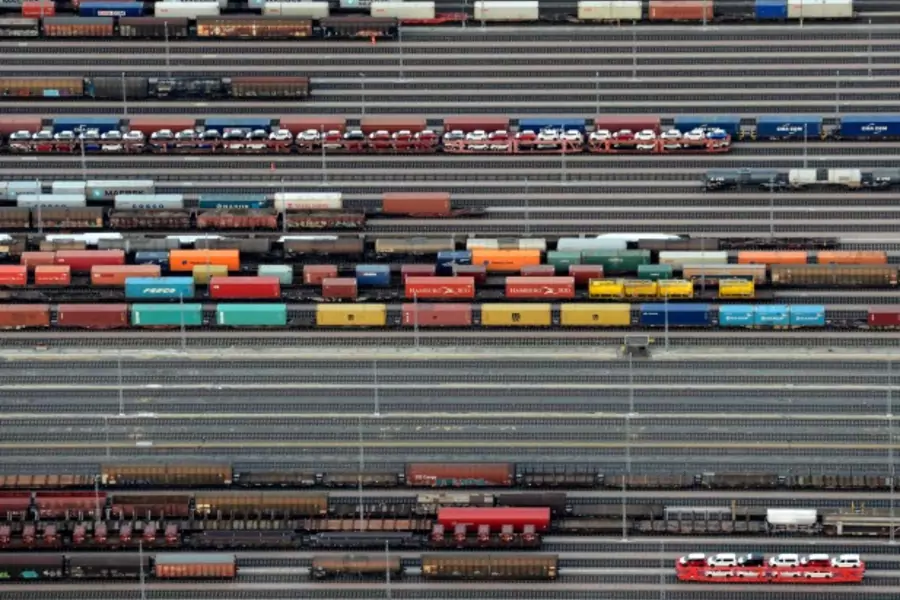

We live today in a networked economy led by investment flows where business-to-business intermediate trade accounts for over two-thirds of the goods and nearly three-quarters of the services exchanged worldwide. Global value chains (GVCs) now define how companies do business and how world trade is structured.

These complex chains mean different things to different actors and the “governance” of GVCs is understood in various ways. It can be viewed from at least three perspectives: of firms; of individual countries; and of the international trading system.

At the firm level, governance of a supply chain refers to management, or how the activities in a production network are organized and carried out among participating firms. Usually the lead firm sets and enforces the parameters under which other firms in the network operate, through deciding what will be produced and in what location, the type of quality controls that must be followed, and the management structure.

Companies are most concerned with generating efficient production to maximize profits. How they position themselves in a given value chain and what type of management or governance structure they adopt will depend partly on the type of activity in which they are involved.

Sovereign nations look at the governance of global value chains as a policy issue. Their goals are to create an environment that will bring in investment, enhance economic growth, and stimulate the transfer of technology and skills. Governments aim to create the most conducive and enabling set of policies that will allow firms to engage in GVC operations.

Both domestic and international policies matter. Domestically, a liberalizing trade policy is a necessary first step to integrating into GVCs. Education, too, is needed for a country’s labor force to contribute high-quality services, or add high-quality inputs to goods and services going into value chain networks. Other enabling policies and factors include:

- a competitive services industry

- investment-friendly policies

- strong government institutions with mechanisms for legal recourse in the case of disputes

- a robust digital infrastructure

- customs and border management for efficient logistics

- non-discriminatory domestic regulation

Governments must push these reforms, all the while balancing domestic politics, which may or may not support this open trade agenda.

Finally, the international trading system governs GVCs through rules negotiated between countries in trade agreements and addresses decisions that affect trade and investment flows between several trading partners or the trading system as a whole. This form of GVC “governance” has been little explored and discussed by analysts and policy officials. Some argue there is a "supply chain governance gap" at the multilateral level due to the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) preoccupation with the Doha Round agenda of 20th century trade issues, and with a WTO system characterized by:

- outdated trading rules—the WTO came into force in 1995 when the internet was considered “emerging technology” and the World Wide Web had just appeared;

- lack of rules on investment, competition policy, and e-commerce and digital trade, all vital to GVC operations;

- trade rules that are structured in silos, with no cross-cutting forum to discuss horizontal issues that affect GVC operations.

In the WTO’s absence, preferential, plurilateral and mega-regional trade agreements have stepped into the governance void. The Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), being negotiated by fifty countries, covers all services sectors as well as key 21st century trade-related issues. Investment, competition policy, and digital trade/data flows are all included in new, deeper preferential trade agreements, such as the recently-concluded Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). If ratified, the TPP should create an enabling environment for GVCs among its members. However, it will further splinter the WTO system. If followed by other preferential trade agreements, it will lead to more fragmentation in GVC governance.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store