Can the debate over trade – or globalization – be separated from the debate over exchange rates?

More on:

I am often struck by how frequently debates over trade – and, more broadly, globalization – don’t bother to mention what strikes me as the most salient fact about contemporary globalization, namely that it has been marked by an enormous amount of government intervention in the foreign exchange market and a huge surge in the sale of US financial assets to emerging market governments.

Rather than trading US made goods for goods made in the emerging world, the US has – over the last say thirty years – financed the growth in its imports from the emerging world by selling US financial assets. That has to have had an impact on the composition of output in the US - -and the distribution of gains on globalization. It has favored those who generate financial assets (and import goods) over those who produce goods, for example.

And it seems increasingly difficult, at least to me, to maintain this pattern is entirely the product of the operation of free markets. Not so long as key governments are intervening so heavily in the foreign exchange market – and hoarding most of the oil windfall.

Take the most extreme example: China.

If 2000, China exported around $250 billion worth of goods, and its government bought about $15 billion of foreign exchange in the market. In 2008, China is on track to export about $1400 billion worth of goods, and its government is on track – at least judging from the April data -- to buy about $900 billion of foreign exchange in the market.

Yet the popular discussion of trade and globalization rarely also mentions the enormous rise in government intervention in the markets – and the surge in the sale of US financial assets to emerging market governments.

Take a look at Eduardo Porter’s argument for responding to the pressures associated with globalization by expanding the scope of America’s social safety net. Or look at Tyler Cowen’s passionate defense of globalization.

Neither mentioned Chinese intervention in the foreign exchange market. Both also left out any mention of how rising oil prices have dramatically increased the foreign assets of the not-so-democratic governments of the world’s oil-exporting economies.

They aren’t alone: most discussions of the difficulties of selling trade to the American public don’t mention the unprecedented rise in government intervention in the foreign exchange market. And for that matter, most discussions of the difficulties explaining the benefits of sovereign wealth funds to the American public don’t mention that many sovereign funds are a by produce of one-sided government intervention in the foreign exchange market.

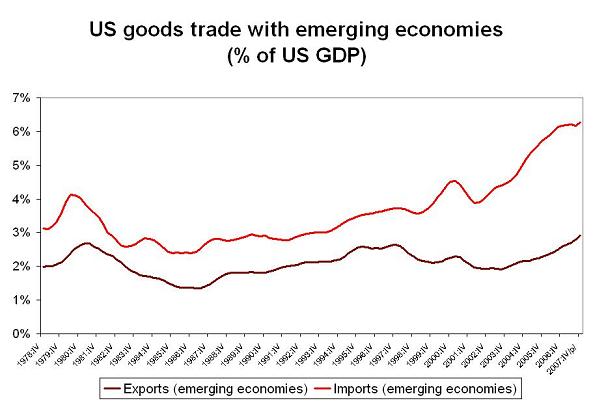

To flesh out my intuition, I went back and looked at US goods trade with the emerging world – setting Mexico* aside – since 1978.

* Mexico is part of NAFTA along with Canada, and splitting the two seemed a bit strange. Moreover, Mexico has allowed its currency to float more freely than most emerging economies.

It is striking that the US doesn’t export much more, relative to the size of its economy, to the emerging world now than it did in 1980 – or, for that matter, in 1997. It just so happens that US exports to the emerging world (excluding Mexico) were 2.6% of US GDP in 1980, in 1997 and in 2007 (they are a bit higher in 2008). US imports from the emerging world by contrast fell from 3.9% of US GDP in 1980 (when oil was high) to 3.7% of US GDP in 1997 and then rose to 6.2% of US GDP in 2007.

It is also striking that the US now imports a lot more from the emerging world than it exports. Paul Krugam is right. US imports from the emerging world are no longer small, and they have been growing rapidly.

So how has the US balanced the rise in its imports of goods from the emerging world?

By selling debt to the emerging world, and recently by selling debt to the governments of the emerging world. My estimates of the growth of the emerging world’s dollar reserves (which require making an assumption about the currency composition of the countries that do not report data to the IMF; see the notes at the bottom) suggest that the growth in the sale of US financial assets to the emerging world has exceeded the growth in US imports from the emerging world.

Why does this all matter? Well, economically, I suspect that the US debate over globalization would be quite different if US exports to the emerging world had grown together with US imports. The winners from globalization woud not be as obviously tied to the financial sector. The shift from central bank reserves to of sovereign wealth funds won’t change the distribution of winners either: the financial sector expects to take a far bigger cut on the sale of US financial assets to sovereign funds than it gets from the sale of US debt to central banks; and bigger feeds managing money for sovereign funds than for managing the funds of more cost-conscious central banks.

No one has argued that the main benefit of globalization is that it allows America’s bankers to sell US debt – and increasingly shares of American companies – to governments in the emerging world. But that is a fairly accurate description of current trade and financial flows.

Incidentally, Broda and Romalis’ analysis of the distributional consequences of US trade with the emerging world not only predates the rise in food and energy prices, but it also doesn’t look at the distributional impact of rising US exports of financial assets to the emerging world. That strikes me as an important oversight: Dani Rodrik has argued that trade tends to increase the price of things that are exported even as it reduces the price of imports more than it reduces the overall price level. And it is pretty clear that the US is currently "exporting" a lot of financial assets to the emerging world.

A quick point of clarification: the rise in US imports from the emerging world over the past several years hasn’t been driven primarily by the rise in the price of oil. Stripping OPEC out of the data doesn’t change the picture much. At least not yet. The data ends in 2007 -- a year when oil averaged $70. It will average much much more in 2008. US imports from OPEC are set to soar.

*I added Mexico to this graph as well; trade with Mexico isn’t the central story of the past ten years.

And one aside. US imports to Europe, Japan and the NAFTA countries have increased significantly since say 1980. US exports to Europe, Japan and the NAFTA countries, by contrast, haven’t increased that much relative to US GDP. The two periods when US exports to the advanced economies fell relative to GDP – the early 80s and the early part of this decade – both followed periods of dollar strength. Exchange rates do matter.

However, most of the rise in US imports from Europe, Japan and the NAFTA countries came before 2000. The increase in US imports since say 2000 has all come from the emerging world. That is an important change.

Imports (of goods) from the emerging world have gone up significantly relative to US GDP. Exports (of goods) to the emerging world haven’t gone up. Exports of financial assets have.

A major surge in US exports to the emerging world – one that matched the surge in US imports from the emerging world over the past few years -- could change this pattern.

DeLong is hopeful. I wish I could be as optimistic.

Chinese policy making seems frozen, with policy makers unable to decide whether to raise rates (to tame inflation) or cut rates (to curb speculative inflows); or to decide whether to allow the RMB to rise (to curb inflation) or to hold the line (to support exports). Chinese policy makers currently seem to agree on little other than the need to tighten controls on lending and capital inflows. The appreciation of other Asian currencies has stopped. I don’t currently see the kind of consensus globally needed to really address an imbalance as large as the one that has been allowed to build up.

* Two general technical notes.

One: I opted to look at goods trade because I found a longer time series that included more countries. Most US service exports go to the advanced economies, so my sense is that including services wouldn’t change the basic story much. I also believe that tax arbitrage tends to increase the stated US deficit in goods trade with Europe while increasing the US income surplus -- as US and European firms use transfer pricing to shift profits to low-tax European jurisdictions. As a result, I suspect the "true" US trade deficit with Europe is smaller than the data indicates.

Two: My estimates for the sale of US financial assets to emerging market governments are based on my work estimating dollar reserve growth rather than the US data. The US data -- especially the US data prior to the forthcoming revisions (which will incorporate the survey data) -- tends to understate official purchases of US assets. My estimates hinge on two key assumptions: those countries that do not report data to the IMF have a fairly high dollar share of their reserves (around 70%), and the increase in dollar reserves predominantly finances the purchase of US assets, not dollar-denominated debt issued by residents of other countries. I also added in my estimates of the new inflows into the dollar assets of the Gulf’s sovereign funds. Here I make the opposite assumption, namely that the Gulf sovereign funds have a more diversified portfolio than the emerging market central banks who report data to the IMF.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store