Of Course We Can’t Have It All

More on:

Last week, two very different yet equally fascinating publications were released about how we choose to spend our time. One was based on the personal experiences of a prominent international relations scholar and former high-ranking State Department official, the second a statistical database compiled annually by the federal government.

“Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” is the well-read and much-discussed essay by Anne-Marie Slaughter in the current issue of the Atlantic. The essay is long (over twelve thousand words) and makes the thought-provoking—and ultimately convincing—argument that it is needlessly difficult for women to simultaneously advance professionally and raise a family “with the way America’s economy and society are currently structured.”

Slaughter’s main argument has its roots in an unprecedented statement by Ronald Reagan three decades ago, on Women’s Equality Day in August 1985: “Today, women have an unparalleled degree of opportunity to decide what they want to achieve in their lives. Whether they devote themselves to raising families or to pursuing careers, their contributions to America are leaving an indelible mark on our Nation’s life.” While Slaughter does not contend that today’s women face such binary life choices, she does catalogue all of the constraints that make a balanced and fulfilling work-life difficult—and, for her, not worth the costs.

Full disclosure: I played a small cameo role in Slaughter’s essay, which cited my Foreign Policy piece “City of Men” that analyzed the proportionate underrepresentation of women in policy-related positions at think tanks, the academy, military officer corps, and the private sector. If you do the math, you’ll find fewer than 30 percent of senior positions are held by women at these institutions. The problem with working in a field with such a gender imbalance is, as Slaughter notes: “Only when women wield power in sufficient numbers will we create a society that genuinely works for all women. That will be a society that works for everyone.”

In the last year, there have been a number of studies published that support my initial findings. A recent National Journal survey of “558 chief executives of trade associations, labor unions, interest groups, think tanks, and other nonprofits with a significant presence in Washington,” found that just 18 percent are women. Of course, this represents a greater percentage than Fortune 500 companies; last month, female chief executives officers reached an all-time high of eighteen, or 3.6 percent overall.

Slaughter also quoted a blog post that featured six women in a range of foreign policy positions who graciously answered my question: “Women are significantly underrepresented in foreign policy and national security positions in government, academia, and think tanks. Why do you think this is the case?” I invite you to read the other four thoughtful responses that Slaughter did not quote.

Perhaps inevitably, Slaughter has faced a barrage of critical responses that are either personal attacks or fall under the general categories of how the intelligentsia reacts to any presentation. Personally, what I found deeply profound about her essay is how time is valued and prioritized among personal and professional commitments.

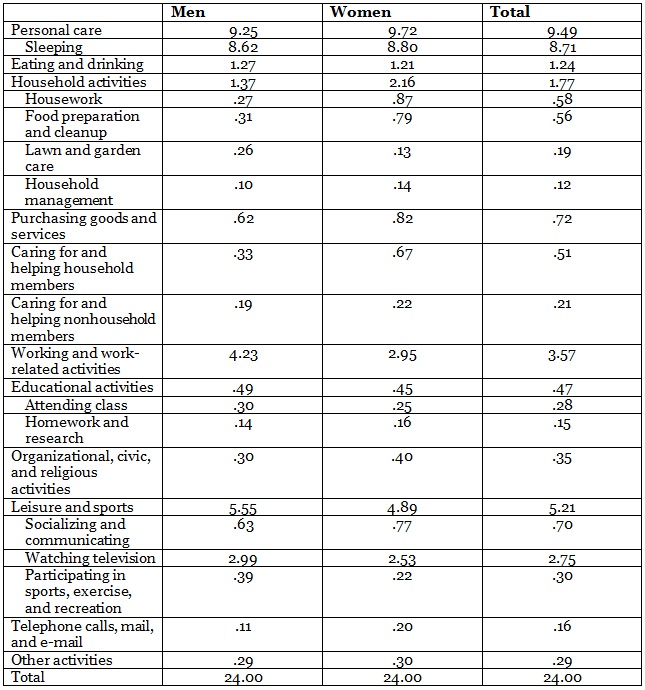

This realization was on my mind when I came across the second noteworthy publication, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual study, American Time Use Survey (ATUS). The survey selects households based on a demographic representation of America, and then interviews a randomly-selected individual fifteen years or older from that household. The findings are broken down by variables such as age, sex, marital status, employment status, and presence and age of children.

The ATUS quantifies the different categories of how people spend their time (see table below). There are many notable and interesting findings that reveal a great deal about the daily activities of the average American. Also, for all the media reports that Americans are getting less sleep, working longer hours, spending less time with their children, or watching too much television, we really haven’t changed much over the past nine years.

The life expectancy of Americans is 78.5 years, or 28,653 days (refine this number further through Census Bureau estimates for the average person of your sex, age, and race). The good news is that we have some ability to increase our lifespan by avoiding four behavioral risk factors.

Carl Sandburg once said: “Time is the coin of your life. It is the only coin you have, and only you can determine how it will be spent. Be careful lest you let other people spend it for you.” Much lies beyond our control—shaped or determined by structural factors, according to Slaughter. However, we have both the agency and responsibility to decide how to spend our time. Are you spending your finite coin on this earth doing what you want? If not, why?

More on:

Online Store

Online Store