Is The Dirty Little Secret of FX Intervention That It Works?

Foreign exchange intervention has long been one of those things that works better in practice than in theory.*

Emerging markets worried about currency appreciation certainly seem to believe it works, even if the IMF doesn’t.**

More on:

Korea a few weeks back, for example.

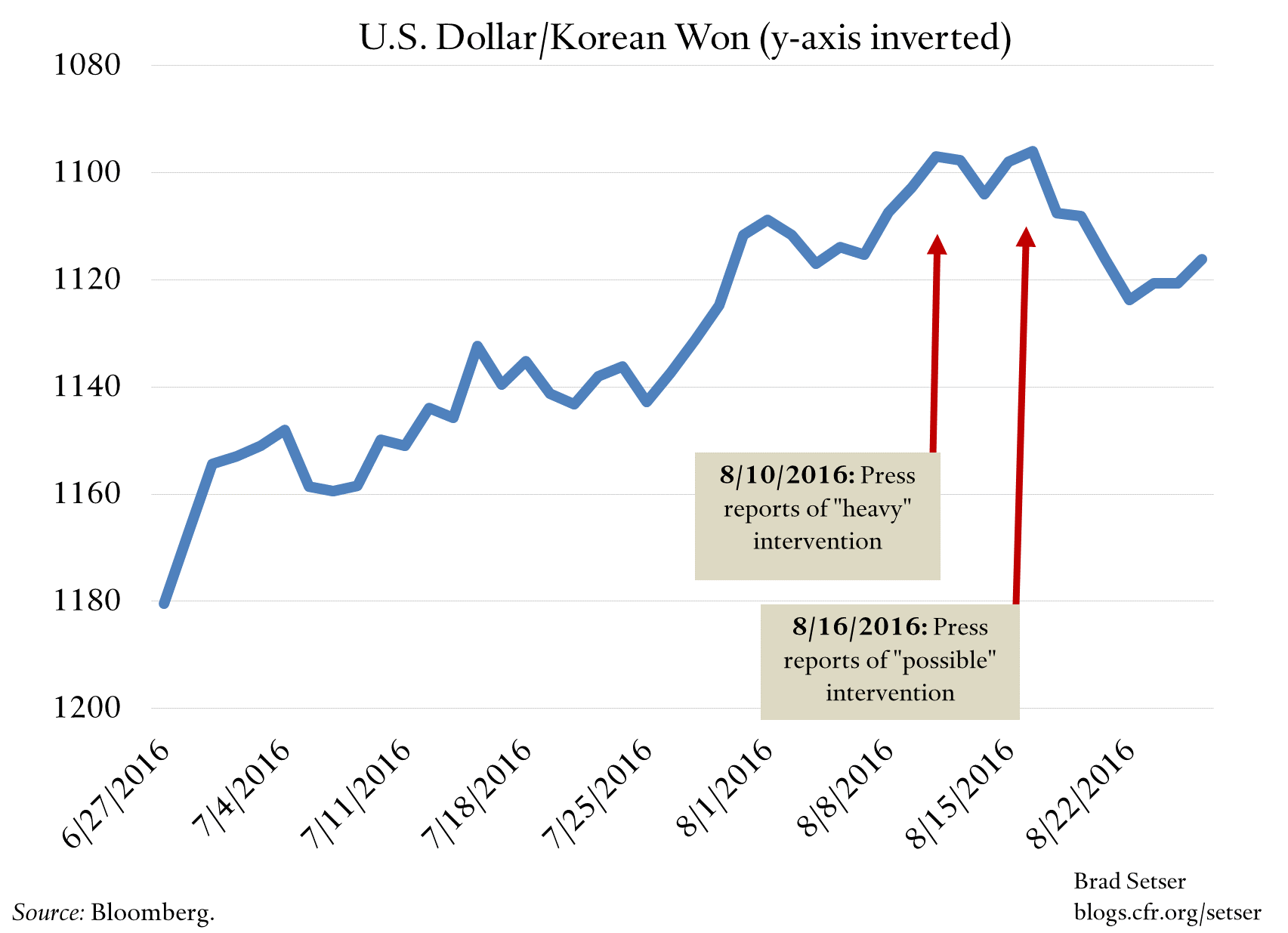

Korea reportedly intervened—in scale and fairly visibly—when the won reached 1090 against the dollar in mid-August:

"Traders said South Korean foreign exchange authorities were spotted weakening the won "aggressively," causing them to rush to unwind bets on further appreciation. On Wednesday (August 10), according to the traders, authorities intervened and spent an estimated $2 billion when the won hit a near 15-month high of 1,091.8."

And, guess what, the won subsequently has remained weaker than 1090, in part because of expectations that the government will intervene again. And of course the Fed.

More on:

And that is how I suspect intervention can have an impact in practice. Intervention sets a cap on how much a currency is likely to appreciate. At certain levels, the government will resist appreciation, strongly—while happily staying out of the market if the currency depreciates. That changes the payoff in the market from bets on the currency. At the level of expected intervention; appreciation becomes less likely, and depreciation more likely.***

1090 won-to-the-dollar incidentally is still a pretty weak level for the won, even if the Koreans do not think so. The won rose to around 900 before the crisis, and back in 2014, it got to 1050 and then 1000 before hitting a block in the market. In the first seven months of 2016, the won’s value, in real terms, against a broad basket of currencies was about 15 percent lower than it was on average from 2005 to 2007.

My guess is that Korea’s practice of intervening to cap the won’s appreciation at certain levels—and systematically trying to keep the won weaker than it was from 2005 to 2008 is part of the reason why Korea runs such a large current account surplus. Just a hunch.

Korea’s tight fiscal policy no doubt contributes to Korea’s large external surplus as well (Korea’s social security fund runs persistent surpluses, surpluses that generally have more than offset the government’s small headline deficit). Intervention and tight fiscal sort of work together. The general government surplus acts as a restraint on domestic demand. And intervention helps sustain a large export sector that offsets weakness in internal demand.

[*] More specifically sterilized intervention (sterilized intervention means the government buys foreign currency, but offsets the domestic monetary impact of its foreign exchange purchases—whether by raising reserve requirements, issuing central bank paper, or by selling domestic assets). Unsterilized purchases of foreign exchange are a monetary expansion, and thus always should have an exchange rate impact. This San Francisco Fed note is a bit old, but it gives a clear summary of the standard argument while arguing that intervention can have an impact; this Cleveland Fed paper is typical of the view that sterilized intervention doesn’t have an impact.

[**] The IMF formally believes—if belief is defined by what is in its workhorse current account model—that foreign exchange intervention only has an impact when a country’s financial account is largely closed. For example, even extremely large scale intervention by say Japan technically would have no impact on Japan’s current account, as Japan’s financial account is considered fully open, and intervention is interacted with the coefficient for openness. Korea’s capital account isn’t fully open, but it is pretty open—so 1 percent of GDP in intervention would, in the IMF’s model estimates, I think have a maximum impact of around 5 basis points (0.05 percent of GDP) on Korea’s current account (the 0.45 coefficient on reserve growth times the 0.13 coefficient on the capital account). However, intervention is only judged to be policy relevant by IMF if there is a gap between the country’s level of reserves and the optimal level of reserves, and if there is also a gap between the country’s controls and the optimal level of controls. As the IMF doesn’t think Korea should throw open its financial account just yet, Korea’s intervention is effectively zeroed out.

Joe Gagnon, Taim Bayoumi and Christian Saborowski found a bigger impact from intervention in their 2014 paper: “each dollar of net official flows raises the current account 18 cents with high capital mobility and 66 cents with low capital mobility, for an average effect of 42 cents.” The impact of an incremental 1 percent of GDP in reserve purchases by Korea is thus about 20 basis points on the current account, plus an additional impact from the legacy of past intervention. A high stock of reserves has an impact in the Bayoumi, Gagnon and Sabrowski model on the current account balance of high capital mobility countries. Korea has well over $400 billion in reserves if you include its $44 billion forward book, or very roughly around 30 percent of GDP; with a stock coefficient of .03 that gives a stock impact of around 1 percent of GDP. Other Gagnon estimates point to a slightly bigger impact of intervention. My guess is that Korea’s long record of intervening to cap appreciation together with its less than complete financial openness combine so that Korea’s actions have a bigger impact than implied by the Gagnon, Bayoumi, and Sabrowski estimates, as past intervention makes Korea’s action in the market more credible (e.g. the market believes that if Korea really wants to stop the won from appreciating it will buy in scale, so it doesn’t test the authorities too much once they show their hand).

Online Store

Online Store