The Health of Nations: New Interactive Disease Map

Laurie Garrett, my irrepressible colleague at the Council on Foreign Relations, likes to push boundaries. It’s certainly worked for her. She’s the only person to have received all the country’s major journalism awards—the Pulitzer, Peabody, and Polk trifecta. Her just completed e-book, I Heard the Sirens Scream: How Americans Responded to the 9/11 and Anthrax Attacks, is selling faster than Tickle-Me-Elmo at Christmas. Not content with her burgeoning print and e-book empire, she’s recently gone Hollywood—as a scientific consultant for the critically acclaimed Steven Soderbergh film, Contagion.

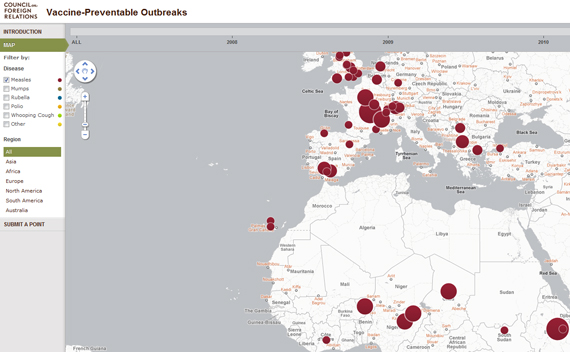

This week she’s achieved another landmark. Her CFR Global Health program has released a user-friendly interactive map on the web that tracks “Vaccine-Preventable Disease Outbreaks” around the world. For the past three years, Garrett and her colleagues have been collecting and plotting global data on the incidence of several common infectious diseases that should be headed for extinction, given their vulnerability to inexpensive and effective vaccines. The five most prevalent are measles, mumps, whooping cough, polio, and rubella. The entire database—to which experts and journalists are invited to contribute—is searchable by disease, region, and year.

More on:

This is an entirely avoidable public health travesty. "These outbreaks illustrate a worrying trend and raise the sense of alarm regarding failures in and public resistance to vaccine efforts," Garrett writes. "Small decreases in vaccine coverage are known to lead to dramatic increases in outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases." The consequences of official failure are stark. Measles, for example, still kills an estimated 164,000 people around the world each year—mostly children under five.

The incidence of new cases remains highest in poor developing countries, which frequently lack the resources—and sometimes the political will—to organize effective immunization campaigns, as well as counter disinformation about the safety of such medication. While it would be easy to dismiss this trend as the sole responsibility of the country, one nation’s poor record of vaccination can have serious consequences even for countries on different continents.

Though it is less visible on their map of outbreaks from the last three years, Nigeria’s abysmal performance in combating polio illustrates the international consequences of weak vaccination programs —as I discuss in my book Weak Links: Fragile States, Global Threats and International Security.

Thanks to Rotary International’s Global Polio Eradication Initiative, polio was on the brink of eradication in mid-2003, remaining endemic in only a handful of countries, including Nigeria, Niger, Egypt, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. But at that critical juncture, officials in several of Nigeria’s northern states abruptly halted immunizations, due to rumors that the vaccination program was a Western anti-Muslim conspiracy that would leave those vaccinated sterile or HIV-infected. Teams of vaccinators were frequently attacked. Ultimately, tens of thousands of parents refused to have their children immunized.

The Nigerian government’s failure to enforce its national immunization program in the face of this ignorance allowed the disease to rebound in Nigeria—and spread across a broad swath of Africa and beyond to the Middle East and Asia. By the time the immunization campaign was resumed in 2005, the Nigerian strain of polio had appeared in seventeen countries—many of which had been free of the disease or on the brink of eradication after decades of global public health efforts. More than six years later, three strains of the polio virus remain in circulation not only in Nigeria but also Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, and China.

More on:

What Garrett’s map makes clear, however, is that the failure to vaccinate is hardly confined to the poor world. Ineffective public health campaigns and resistance to immunization from misinformed parents can wreak havoc on public health in advanced democracies, including the United States. The map shows a dramatic jump in whooping cough in the U.S. West and Midwest in 2010, for example, and a surge in mumps cases on the east coast.

With luck, the Vaccine-Preventable Outbreaks Map will spur complacent politicians in the United States to take more seriously the warnings of public health advocates about the growing vulnerability of the U.S. population to diseases that should have been consigned to history’s biohazard dustbin. And it should help epidemiologists, policymakers, health providers, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies alike identify global infectious disease hotspots and target health interventions accordingly. If it can advance those political and technical ends, Garrett’s map will achieve the sort of impact that is all too rare within the think tank community.

Online Store

Online Store