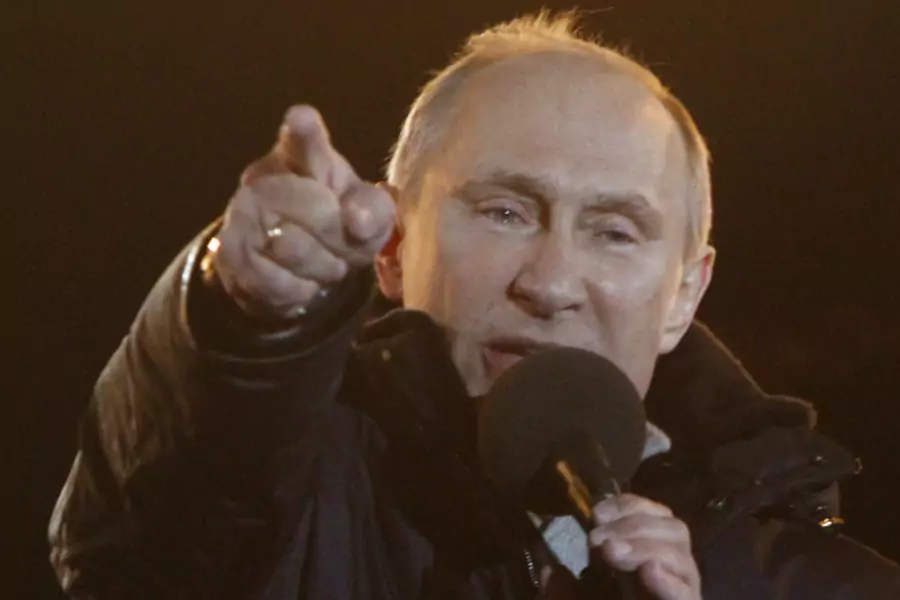

Hello (Welcome Back): Vladimir Putin, Russian President

He’s baaaaaccck! Vladimir Putin, who stepped down in 2008 as Russia’s president after serving two terms, won yesterday’s Russian presidential election going away. He captured a reported 64 percent of the vote, well above the 50 percent he needed to avoid a run-off election but seven percentage points below what he captured in his last presidential run in 2004. Putin was defiant in victory, telling his supporters who had gathered outside the Kremlin, “We have shown that nobody can impose anything on us.” (He did tear up at one point during his victory speech, but he attributed that to cold weather and a high wind rather than the emotion of the moment.) A record number of election observers turned out to supervise the voting, but that hasn’t stopped allegations that Putin’s supporters perpetrated election fraud. Whether these charges stick, and more importantly, fuel the protests first triggered by the fraud committed in Russia’s December parliamentary elections, remains to be seen. What is certain is that Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin is once again running Russia.

The Basics

- Name: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

- Date of Birth: October 7, 1952

- Place of Birth: Leningrad, USSR (now St. Petersburg, Russia)

- Religion: Putin refuses to state his religion publicly.

- Political Party: United Russia (center-right)

- Marital Status: Married on July 28, 1983 to Lyudmila Putina (née Shkrebneva)

- Children: Mariya Putina (b. April 28, 1985) and Yekaterina Putina (b. August 31, 1986)

- Alma Mater: Leningrad State University (graduated in 1975 and wrote his thesis on international law)

- Past Political Positions: Prime Minister (May 8, 2008 – May 8, 2012), President (May 7, 2000 – May 7, 2008)

Personal History

More on:

Putin’s parents survived the Siege of Leningrad during World War II. His father was seriously wounded during the war, and his mother did backbreaking manual labor in factories. Putin won’t say what religion he practices, or if he practices any religion at all. His father was a “militant atheist,” while his mother was Russian Orthodox and had Putin baptized.

Putin’s upbringing was spartan. According to Masha Gessen, the author of The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin:

The Putins lived on the top floor of the five-story building, and the journey up the dark stairs could be risky. Three families shared a single gas stove and a sink stationed in the narrow hallway. The Putins had the largest room in the shared apartment: around 20 square meters, or roughly 12 feet by 15 feet.

Putin wasn’t a model student. He got into so many fistfights that he was barred from joining the Pioneers, the Soviet Union’s organization for teenagers. What got him on the straight and narrow was sports. As Putin writes in his autobiography:

If I hadn’t gotten involved in sports, I’m not sure how my life would have turned out. It was sports that dragged me off the streets.

More on:

Putin’s sport of choice was judo. He got pretty good at it, winning the Leningrad city championship. He continues to this day to don the judogi and hit the mat to display his moves.

Before meeting his wife, Lyudmila, Putin dated a woman that he eventually left at the altar. He and Ludymila dated for three years before getting married. According to Masha Gessen, meeting Putin was not love at first sight for Lyudmila. Putin and Lyudmila are seldom seen in public together, and little is known about his two daughters. According to Time, no confirmed photographs of them in adulthood are publicly available. Putin has denied rumors that he and Lyudmila are divorced or separated. The denials haven’t stopped journalists from suggesting that he is romantically involved with Alina Kabaeva, a former Olympic champion in rhythmic gymnastics who is three decades his junior.

Career

Putin says he always wanted to be in the KGB. In high school, he went up to an on-duty officer and said “I want a job with you.” The officer told him to go to the university and get a law degree. Putin dutifully followed the advice.

Putin graduated from Leningrad State University in 1975 with a law degree, and the KGB subsequently accepted him. His first job (as far as we know) was spying on foreigners in Leningrad. He was then assigned to a post in Dresden, East Germany. (Putin speaks fluent German.) Putin’s daughters were born there.

Putin stayed in East Germany until 1989 when he became the head of the Foreign Section at Leningrad State University. It was back at his alma mater that his political career began. Putin worked for his former law professor, Anatoly Sobchak. Sobchak was heavily involved in Leningrad politics, and he asked Putin to come with him as the international affairs advisor to Leningrad’s city hall. When Sobchak became the city’s mayor in 1991, he made Putin the chairman of Leningrad’s foreign affairs committee.

Putin’s work in Leningrad helped him catch the eye of the Russian president, Boris Yeltsin. He appointed Putin as the first deputy head of the presidential administration in 1998. Putin’s job was to help relations with Russia’s forty-six regions, twenty-one republics, nine territories, and seven other areas. Putin was then named the head of the Foreign Security Service (FSB), as the counterintelligence parts of the KGB came to be called after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Yeltsin surprised many Russia hands by asking Putin to be the prime minister on August 9, 1999. Just over four months later, Yeltsin resigned as president and named Putin his successor. On March 26, 2000, Russia held presidential elections, and Putin won with fifty-two percent of the vote.

Putin’s two terms as president had their tumultuous and controversial moments—the Khodorkovsky trial, the seizure of multiple media outlets, the Beslan school massacre, and wars with Chechnya and Georgia. But Russia prospered economically under his leadership. Not surprisingly, Putin became Russia’s most popular politician. He still holds that honor today, although his poll numbers are nowhere near as high as they were four years ago. He has benefited from the fact the public holds his political foes in even lower regard.

Term limits barred Putin from running for reelection in 2008. He handed the presidency to his chosen successor, Dmitry Medvedev, while he took Medvedev’s place as prime minister. In September 2011, Putin let it be known that he intended to run for president again. Under Russia’s current constitution, he could run for election for another six-year term in 2018 and remain as president until 2024. If he retires in 2018 he will have matched Leonid Brezhnev’s tenure in running the Soviet Union—eighteen years. Does he intend to run again in 2018? Putin says “I have not yet made this decision” but that “it would be normal, if things are going well, and people want it.” Although twenty-four years in charge of running Russia sounds like a lot, it would leave Putin well short of the thirty-one years that Josef Stalin spent running the Soviet Union and the fifty-one years that Ivan the Terrible reigned over Russia. Of course, neither Stalin nor Ivan had to worry about how well they were polling.

Putin in His Own Words

Much is made of Putin’s character having been defined by his time in the KGB. Putin appears to agree. He says “there is no such thing as an ex-KGB agent.” He has had no problem stacking the Russian government with his former KGB friends and colleagues.

Americans say they want government out of their lives. Putin won’t have any of that. He thinks that the Russian state should be central in the lives of the Russian people in order to maintain order:

For us, the state and its institutions and structures have always played an exceptionally important role in the life of the country and the people. For Russians, a strong state is not an anomaly to fight against. Quite the contrary, it is the source and guarantor of order, the initiator and the main driving force of any change…Society desires the restoration of the guiding and regulating role of the state.

Does Putin long for the glory days of the Soviet Union? Maybe, maybe not:

Anyone who doesn’t regret the passing of the Soviet Union has no heart. Anyone who wants it restored has no brains.

Putin’s critics say that his tenure as Russian leader has been dictatorial in nature. He claims, however, that he is a fan of democratic government:

History proves that all dictatorships, all authoritarian forms of government are transient. Only democratic systems are not transient. Whatever the shortcomings, mankind has not devised anything superior.

Indeed, according to Putin he is advancing democratic governance in Russia:

Nobody and nothing will stop Russia on the road to strengthening democracy and ensuring human rights and freedoms.

Putin still has to convince his critics that he means what he says. His critics at home have labeled his political party, United Russia, the “party of crooks and thieves.”

Putin’s Challenges

Putin has plenty of work to do as he returns to the presidency. Russia was hit hard by the 2008-2009 global financial crisis; its GDP fell eight percentage points in 2009. The crisis exposed Russia’s vulnerability to changing oil and gas prices. When they are up, Russia does fine. But when they fall, as they invariably do in a global recession, Russians suffer.

Russia’s problems do not stop with an economy that depends too much on oil and gas prices. Russia is also grappling with an aging and shrinking population, a high rate of alcoholism, a decaying infrastructure, a declining industrial sector, a sagging education system, a high economic crime rate, a weakened military, and political corruption. This is a daunting list of things to fix. One former Russian prime minister, Mikhail Kasyanov, says that as long as Putin is president they won’t get fixed.

One reason that many of these problems are likely to linger is that Putin doesn’t see the need for significant change. During the campaign he acknowledged that Russia confronts many challenges, but largely dismissed calls to dramatically revamp its economic policies, business practices, and legal rules. He instead defended the policies he has favored over the past fifteen years, which means heavy reliance on state-led economic growth.

Putin also faces a public angry with the fraud that plagued Russia’s December 2011 parliamentary elections and prompted nationwide protests. Will this anger have lasting consequences? Some Russia-watchers are optimistic about what the recent protests in Russia might signal, perhaps even an end to “Putinism.” Others are far less sanguine. The New Yorker’s David Remnick writes: “millions of Russians remain apolitical and atomized, and have learned to live with a system that provides few legal guarantees but does offer some economic advancement.” Or as the Economist puts it, Russians are still laboring under the debilitating habits of “Homo Sovieticus.”

Putin, the Russian Military, and NATO

Putins says he intends to rebuild Russia’s military. Russia has spent around four percent of its GDP on its military since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but the money hasn’t necessarily been spent wisely. Russia has slightly fewer active-duty troops than the United States does—1 million versus 1.1 million–but the size of the Russian armed forces is far smaller than the 4.3 million that served in the Soviet Red Army in 1986.

Why the focus on the military, especially when Russia faces so many other problems? Putin has made no secret of his desire to make Russia a global power once again, and a global power needs a strong military. Plus, Putin is no fan of NATO. As the Congressional Research Service’s Jim Nichol argues, Russia’s national security strategy:

military doctrine, and some aspects of the military reforms reflect assessments by some Russian policymakers that the United States and NATO remain concerns, if not threats, to Russia’s security.

Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 was notable for its use of cold war-esque rhetoric on NATO and the West. He has made no secret of his belief that NATO has been encroaching on Russia’s sphere of influence. Moscow formally warned Georgia in June 2008 against joining NATO, and Tbilisi’s overtures to the alliance may have been a motive for Russia’s military incursion into Abkhazia and South Ossetia later that summer. Nonetheless, Putin claims he doesn’t oppose NATO; in fact, he could see Russia becoming a member:

Russia is a part of European culture. Therefore, it is with difficulty that I imagine NATO as an enemy.

If Russia were to join NATO, it would likely have to be a very different NATO than the one that exists today. NATO’s intervention in Libya deeply angered Russian officials.

Putin and the United States

George W. Bush famously saw Putin’s soul in the summer of 2001, and U.S.-Russian relations subsequently improved after 9/11 with much greater counterterrorism cooperation. Those relations began to sour during Bush’s second term in office. Barack Obama entered the White House seeking to “reset” relations with Russia. The reset did not go as well as Obama wanted, but it did produce the New START treaty in late 2010.

In the coming months, U.S.-Russian relations will likely be testy. While President Medvedev frequently seemed to be sympathetic to the West, Putin has vowed to stand up to it. Criticism of an overbearing United States was one of his favorite themes on the campaign trail. Some Russia experts expect Putin to moderate if not ditch his anti-American rhetoric now that the election is behind him. That doesn’t mean, however, that he will necessarily be more accommodating to U.S. positions on critical issues.

Two issues in particular are likely to strain U.S.-Russian relations: Syria and Iran. On February 4, 2012, Russia joined with China in vetoing a UN Security Council resolution that would have condemned the Syrian government’s violent crackdown on its opponents. Part of the reason for Moscow’s veto is that it has significant military and economic interests in Syria. Russia sold about $1 billion dollars in weapons systems to Syria in 2010, or about 10 percent of its arms sales abroad. Russian firms are also involved in “drilling wells and building…gas processing plant[s]” in Syria. These interests, coupled with Putin’s desire to reassert Russian influence, make it unlikely that Moscow will cooperate with Washington’s efforts to push Bashar al-Assad from power.

Russia once had a strong nuclear energy partnership with Iran, building a nuclear power plant near the town of Bushehr. However, Russian leaders have said on multiple occasions that they do not want Iran to have nuclear weapons. Russia has joined the United States and the UN Security Council in sanctioning Iran because of its nuclear activities. But Russia does not favor all sanctions on Iran; it considers the current round of sanctions to be “unacceptable.”

Medvedev said after meeting with President Obama in 2009 that the international community’s task on Iran:

is to create such a system of incentives that would allow Iran to resolve its fissile nuclear program, but at the same time prevent it from obtaining nuclear weapons.

Putin, however, says he is “worried about the growing threat of a military strike against Iran.” Should Israel or the United States launch a military strike against Iran’s nuclear facilities, expect Putin to lead the parade condemning the action.

Online Store

Online Store