How Japan’s Pacifist Constitution Shapes Its Approach to Cyberspace

Mihoko Matsubara is an adjunct fellow at the Pacific Forum. You can follow her @M_Miho_JPN. Alex Grigsby, assistant director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy program, contributed to this post.

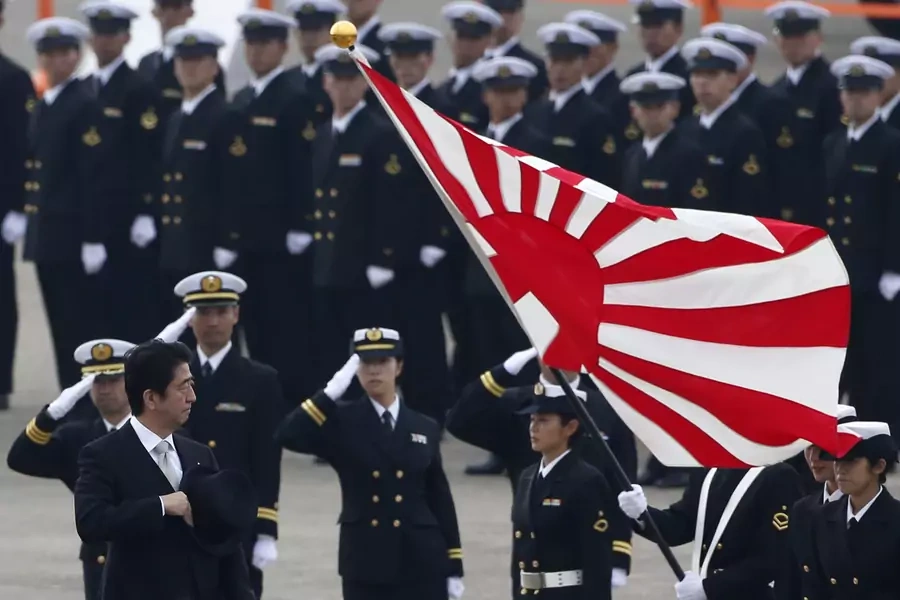

The Japanese government plans to revise its National Defense Guidelines by the end of 2018, which are expected to strengthen the cybersecurity of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) and give them an offensive cyber capability. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced the revision earlier this year to contend with a rapidly evolving security environment, particularly with respect to North Korea and recent ransomware incidents.

More on:

There has been little public debate in Japan about the use of offensive cyber operations as a foreign policy tool, let alone their military use given the country's war-renouncing constitution, which permits Japan only to possess the bare minimum of self-defense capabilities. To date, not much has been made public about the Japanese government's thinking on the matter aside from a 2012 document that says Tokyo will decide what constitutes an armed attack in cyberspace on a case-by-case basis, and that the SDF created a cyber unit in 2014.

According to a recent government consultation document, Tokyo is looking to focus a significant portion of its revised national defense strategy on deterring adversaries in cyberspace—a first for the country. As over thirty countries develop offensive cyber capabilities, Japan seeks to specifically deter cyber operations that can disrupt Japan’s national security or threaten the lives or rights of Japanese citizens. The document also notes that Tokyo will use all of its diplomatic, economic, and technological means to achieve its deterrence aims, though it interestingly never references the use of the SDF as part of its deterrent. Japan’s emphasis on deterrence is consistent with discussions it has had with the United Kingdom and the United States.

So far, there has been little discussion on how exactly Japan will deter adversaries. There are generally two approaches to deterrence: by punishment or by denial. Under the first approach, Japan would threaten adversaries with a punishment so severe that they would refrain from attacking it. Effectively punishing adversaries in cyberspace requires a lot of preparatory work, much of which needs to be done before an attack occurs. For example, if Japan wanted to shut down an adversary network in response to an attack against it, Japanese cyber operators will need to have already identified which networks are important to the adversary, what software they run and vulnerabilities it might have, and exploited them. This preparatory work should ideally take place before Japan is attacked if it is to punish its attacker a timely manner and send the signal it wants to send. Under the constraints of Japan’s constitution, it’s unclear whether any of these offensive operations to prepare the battlefield, even in support of deterrence approach or to respond to an armed attack, would be legal.

The second approach, deterrence by denial, requires Japan to improve its cyber defenses to the point where any prospective adversary would simply not bother attacking it given that the costs of attack outweigh any benefit. That would require that Japan understand the cyber threats it faces, and make the necessary strategic investments in cybersecurity technologies and professionals across the Japanese government and business.

That may prove challenging because the Japanese employment system and intelligence community differ completely from those in the United States or the United Kingdom. Japan still largely depends on a lifetime employment system, where an employee will start with one company and remain there until he or she retires. As a result, cybersecurity experts that have cut their teeth in the Japanese government or intelligence communities rarely move to the private sector. The lack of cross-pollination between the government and private sector also makes it challenging for government to understand the threats business face and how to protect them. Deterrence by denial won’t work if Japan does not avail itself of all of the tools at its disposal to increase the costs to prospective attackers.

More on:

Japan’s emphasis on deterrence, and the challenges that brings, comes at the same time that the United States, its most important ally and security guarantor, seems to be shifting away from that approach to cyberspace. According to a new U.S. Cyber Command strategy, Washington has largely given up on deterrence given that very few cyber operations raise to the level of an armed attack and makes them impossible to deter. Instead, the United States will pursue a strategy of persistence to contest an adversary’s capability. In other words, the U.S. cyber operators will engage in “hand-to-hand” combat with adversaries in cyberspace to achieve superiority, instead of trying to change an adversary’s calculus from attacking in the first place.

The U.S. emphasis on persistence, however, is not necessarily applicable to Japan given its pacifist constitution. If most cyber operations occur below the armed attack threshold and Japan cannot use the SDF until it is attacked, Japan likely has little leeway to engage in hand-to-hand combat online.

Notwithstanding the challenges Japan faces in developing a doctrine for offensive cyber operations, the fact that it is having the discussion in public at all is a welcome development. The WannaCry incident galvanized Japan’s attention, and for the first time, the country joined the United States, United Kingdom and others in attributing the cyber operation to North Korea. It is vital for Japan to start a conversation on intelligence, deterrence, and what it can and can’t do in cyberspace within its constitutional constraints.

Online Store

Online Store