How Low Can Mario Go?

More on:

In September 2014 the European Central Bank lowered its deposit rate to an all-time low of -0.2 percent, after which ECB President Mario Draghi declared that rates were “now at the lower bound.” What he meant by this was that, by the ECB’s calculations, banks would find holding cash more attractive than an ECB deposit at rates below -0.2 percent, so there was no scope for encouraging banks to lend by pushing this rate lower. The ECB therefore turned to asset purchases, whose efficacy is much in debate, in an effort to ease policy further.

But was Draghi right? Had the ECB actually hit “the lower bound,” or could it have usefully cut the rate lower? The answer is important, because negative deposit rates above the lower bound encourage banks to “use it or lose it” – that is, to lend.

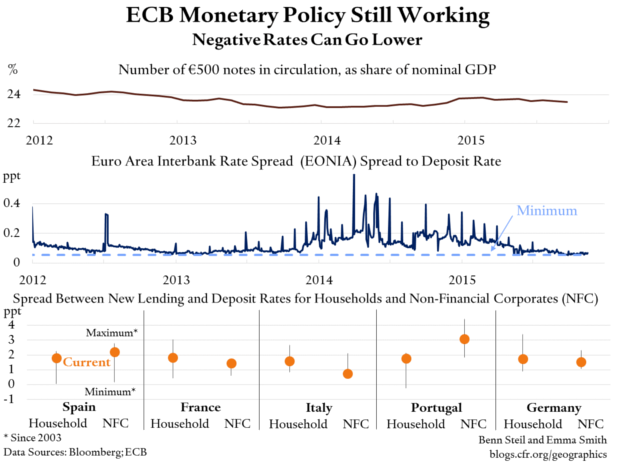

One way to determine whether Draghi was right is to look at what’s happened to the number of €500 notes in circulation. If the ECB had hit the lower bound on deposit rates, then this number should have risen as banks accumulated cash in vaults. But as the top figure above shows, it’s barely budged: banks do not seem to have moved into cash to avoid negative rates.

Another piece of data to check is the spread between the ECB’s deposit rate and the rate at which banks are willing to lend to each other overnight (“EONIA”). Normally, the deposit rate and the interbank rate move in tandem, as banks are generally willing to lend money at a set rate above what they can get from the ECB. But when the deposit rate falls below the lower bound, banks no longer pay it any heed: they just hold cash, and the spread rises. But as we see in the middle figure above, it has not – the spread has in fact fallen back to its historic low.

A final piece of data that might suggest we were at the lower bound is bank net interest margins. If banks are already paying 0 percent on customer deposits, then any cut in their lending rates would have to come out of lending margins – that is, profits on lending. At the lower bound on the ECB’s deposit rate, then, further cuts may not stimulate banks to cut their lending rates. On average, however, eurozone banks are still paying 0.7 percent on new household term deposits with a maturity of less than a year, and 0.25 percent on commercial deposits. There is, therefore, scope for such deposit rates to fall further. Additionally, whereas the spread between new lending and deposit rates for both households and businesses has generally fallen over the past several years, as we see in the bottom figure above, it remains at or above the historical average in most countries. Finally, reported Q1-2 2015 net interest margins for Europe’s largest banks are generally not low by historical standards. This suggests that banks may well be willing and able to withstand further compression of lending and deposit rates.

In short, the evidence suggests that Draghi was wrong. The ECB, we believe, could stimulate lower lending rates and more lending through further cuts in its deposit rate.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store