A myth?

More on:

If net exports had contributed as strongly to US GDP growth over the past three years as they have contributed to Chinese GDP growth, the US would not have a current account deficit - and the US wouldn’t need to rely on oil funds and China’s central bank for as much financing as it does now.

There really isn’t much doubt about this. My rough calculations suggest that net exports contributed 2.6% to China’s GDP growth in 2005, 2.1% in 2006 and are on track to contribute another 2.4% in 2007. No other major economy -- at least no other commodity-importing economy -- has received a similar boost from net exports. Not Europe. Not the US. Not Japan. I would bet that no major economy had received as large a boost from net exports over a three year period in the post-war period.

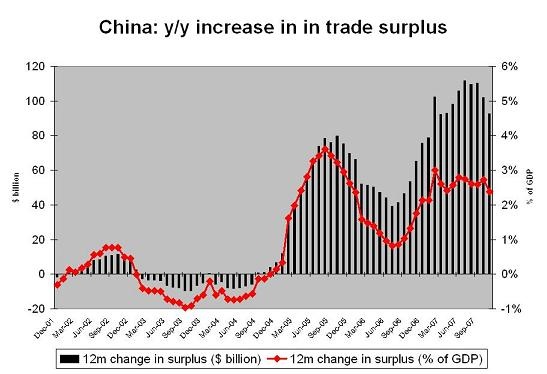

China’s trade surplus rose from $32b in 2004 (census basis) to $260b over the last 12 months of data (up from $180b or so in 2006) even as the average price of oil rose from $33 to $70 (average annual price— it oil averages $100 over 2008 that would be a huge change, even from 2007) and other commodity prices rose as well.

The fact that China is set to run a $350b or so current account surplus at a time when the oil exporters are running a comparable surplus goes a long way toward explaining why large imbalances have persisted in the global economy. Normally commodity importers surpluses do down when commodity prices go up.

The Economist isn’t convinced. This week’s Economics focus column - which draws on work by UBS’s Jon Anderson and builds on previous Economics focus columns arguing that the RMB isn’t really undervalued despite a huge depreciation against the euro and pound, record reserve growth and the record recent contribution of net exports to China’s growth -- argues that China’s economy doesn’t really depend on exports all that much. The Economist:

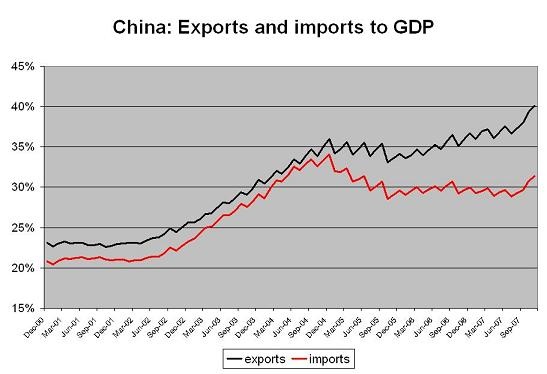

"Headline figures show that China’s exports surged from 20% of GDP in 2001 to almost 40% in 2007, which seems to suggest not only that exports are the main driver of growth, but also that China’s economy would be hit much harder by an American downturn than it was during the previous recession in 2001. If exports are measured correctly, however, they account for a surprisingly modest share of China’s economic growth."

It is no doubt true -- as the Economist argues - that looking simply at the export to GDP ratio overstates exports impact on China’s economy. China has to import (components) in order to export (finished goods). Many other countries do as well, including the US. Boeing aircraft, for example, now have more imported components than the past.

But I am not sure that Jon Anderson’s story - namely that China has shifted from industries like toys with a high Chinese value-added to industries like electronics with a low Chinese value-added, so the value-added in China’s export sector hasn’t increased along with China’s exports - really works. Electronics assembly shifted to China some time ago. The story of the past few years has been the shift in electronics component production to China. A fair amount of data now suggests that the reason why Chinese imports from Asia haven’t grown along with Chinese exports is that China is producing more components at home.

The IMF’s work on this topic (see Box 2 of the April 2007 regional outlook, this Murtuza Syed/ Li Cui paper, and this Li Cui article) might even make for an interesting Economics Focus column. Li Cui’s conclusion -- that China’s exposure to the global economy is rising -- is quite different than Anderson’s conclusion.

I never have quite been able to quite figure out how Anderson reconciles his data showing that the domestic value added in China’s export sector is only around 10% of China’s GDP with the data showing that China’s trade surplus is about 9% of China’s GDP. China’s export sector presumably generates enough net revenue to cover the bill for the commodities China imports and still generate a large surplus that fuels reserve growth.

Anderson’s work suggests the big surge in Chinese value-added came in the mid-1990s and that Chinese value-added has only increased modestly since then. The trade data -- and specifically the soaring trade surplus after 2004 and the end of the close correlation between Chinese exports and Chinese imports -- suggests a more recent surge in Chinese value-added.

(sorry about the swiggly line -- I was in a hurry, and I didn’t smooth the quarterly GDP data to match it with the monthly trade data)

(sorry about the swiggly line -- I was in a hurry, and I didn’t smooth the quarterly GDP data to match it with the monthly trade data)

I suspect Anderson would argue that it is impossible to reconcile the domestic value-added data with the external trade data as the data come from fundamentally different sources and, well, Chinese data never quite adds up. But the gap does seem to suggest - at least to me - that something is off.

Anderson might argue that the trade data is off, as the trade surplus includes large disguised capital inflows. Perhaps. But it is hard to believe that illegal capital inflows account for the full increase in the trade surplus. Not when China has been trying hard to crack down on inflows.

An undervalued exchange rate doesn’t just influence the economy by promoting exports, it also can encourage import substitution.

And an import substitution story certainly fits in well with the data, as imports fell as a share of Chinese GDP from late 2004 on. China arguably has been so effective at substituting domestic production for a range of imports that it basically no longer imports anything other than commodities (and planes), so almost all the value-added in the export sector ends up contributing to China’s surplus. I suspect that this is a large part of Anderson’s argument - it certainly fits the data. It just didn’t though figure in the Economist’s column.

At the same time, I would bet that the fall in the pace of import growth recently also indicates a real increase in share of value-added in China’s export sector, and specifically an increase in the value-added of China’s electronics industry. The IMF argues that "China is becoming less reliant on other Asian economies for inputs" as a result of "rapid investment in the early 2000s" in intermediate sectors. And the growth of Chinese machinery parts exports clearly represents an increase in Chinese value-added.

To be sure, net exports "only" account for between 2 and 3% of China’s recent growth. The Economist is right to argue that China would be growing quite fast even in the absence of any contribution from net exports to growth.

At the same, consumption is still falling relative to GDP, so it clearly hasn’t been the key driver of growth. Investment by contrast has been rising quite sharply relative to GDP. No doubt the majority of that investment has been "domestic" - though if investment in import-competing sectors is factored in, the share of investment in the "tradables" sector likely would be a bit higher than the folks at Dragonomics estimate. It took at least some investment to create the capacity to raises exports v GDP from a bit under 25% of China’s GDP to close to 40% of China’s GDP -- the rise in China’s exports relative to GDP over the last six years exceeds total US exports as a share of US GDP. It also took some investment to bring imports share of GDP down from 35% (in 2004) to around 30% in 2007 -- the recent rise in imports to GDP reflects the recent commodity price spike.

That said the biggest risk to Chinese growth isn’t a collapse in export demand. It is a collapse in domestic investment following China’s current boom. Negative real rates arguably are encouraging massive over-capacity. If investment to GDP fell back to a more normal level for high growth Asian economies, Chinese growth would slow significantly.

Nonetheless, the fact that net exports "only" account for 20 to 25% of China’s overall growth doesn’t change the fact that net exports have contributed more to China’s growth over the past few years than at any time in the past. See the Peterson Institute’s Nick Lardy.

China didn’t run a big trade surplus three years ago. It now does. That presumably is a rather important story, not one to minimize.

That brings up another issue - how best to report to report changes in the value of China’s currency. The Wall Street reported that China’s currency surged last week - and it did, against the dollar. But it actually fell against the euro last week. And even as it soared by 7% against the dollar in 2007, it fell by 3% or so against the most important currency of its largest trade partner (Europe).

In 2007, the RMB depreciated against the euro, the Indian rupee, the Thai baht, the Canadian dollar and the Brazilian real. It held its own against the yen and Malaysian ringit. It appreciated against the US dollar, the Saudi riyal, the pound and the Korean won. But it had depreciated significantly against the won and pound in the past - and it didn’t make up all that much.

That doesn’t sound like a strong currency to me.

To be fair, James Areddy’s story does a better job of most of reporting on the moves in the rmb/ euro, not just the rmb/ dollar - the headline didn’t do justice to the story. Areddy also does an excellent job of highlighting how China is increasingly leaning on the banks to buy dollars, and thus intervening more than ever in the fx market even as the pace of RMB appreciation picked up.

"The mechanics of China’s exchange-rate policy remain murky. Currency traders in Shanghai, where the yuan trades, say recent strength has masked how much more active the People’s Bank of China has become in managing the exchange rate.

Even as it has repeatedly published ever-higher daily "parity" rates for the yuan against the dollar, which establish the parameters for daily trading, it has set highly technical rules that introduce artificial market demand for U.S. dollars, such as requiring banks to set aside more of their deposits as reserves in the U.S. currency."

Don’t get me wrong. The fact that China didn’t follow the dollar down (at least not entirely) is an improvement over say 2003. Unlike some, I do think the RMB’s depreciation in 2003 had something to do with the emergence of China’s trade surplus, and the rapid rise in its surplus with Europe.

And the fact that inflation in China topped inflation in the US meant that the RMB appreciated even faster in real terms against the dollar than in nominal terms. If that is sustained for several years, it should have an impact.

But China’s currency will only surge (in real terms) if:

Chinese inflation increases to Qatari or Emirati levels, which will produce a surge in its real value

The RMB starts appreciating faster against the dollar than other major currencies

Or the dollar stabilizes and China continues to let its currency appreciate at the same rate as in 2007.

Update: The key claim in Jon Anderson’s paper is that the "actual contribution [of exports] to [China’s] GDP is barely rising over time." Anderson also notes that industrial output as a share of GDP (measured on a value-added basis) of GDP hasn’t increased in line with China’s the increase in China’s export to GDP ratio, and that the big increase in exports share of industrial output (in the Chinese data) came in the early 1990s. That raises a puzzle -- namely the huge increase in exports to GDP doesn’t seem to be reflected in the domestic data.

Anderson reconciles these two data series by in effect asserting that value-added in the export sector has to have fallen over time. More exports, falling value-added = same share of total value added in the industrial sector. Fair enough.

And he uses a lot of assumptions and ballpark math -- with the key assumption that makes the ballpark math work being that China’s value added in electronics production is low and stable -- to argue the Chinese export value-added is falling over time. He estimates that domestic content in electronics is far lower than in light manufacturing (toys), and, crucially, that domestic content in electronics has been roughly constant from 2004 on (see Anderson’s chart 7). I can hardly criticize Dr. Anderson for using ballpark and assumptions to make data series that otherwise seem inconsistent a bit more consistent, as I do the exact same thing to estimate official financing of the US.

However, the story that emerges from Anderson’s work -- and it is in some sense the story required to make the stable share of industrial production to GDP consistent with the export data -- is one where value-added in the export sector falls over time. That story seems inconsistent with the rise in the trade surplus -- which suggests a rise in value added as the imports aren’t rising in line with exports. Anderson’s rebuttal is that the fall in imports is more or less all from a fall in import growth, and specifically "excess capacity creation in heavy industrial sectors." Think chemicals and steel.

The work of the IMF and World Bank by contrast tells a slightly different story, namely one where the domestic content of Chinese electronics imports is rising over time. That explains why Chinese exports are growing faster than Chinese imports, and why China’s trade deficit with Asia is no longer rising to offset the growth in its surplus with Europe and the US. This story isn’t inconsistent with the fall in "heavy" imports -- though it suggests that the fall in heavy imports has been accompanied by a fall in light imports.

This story fits the external data (in my view) a bit better than Anderson’s story. But it has its problems -- as it implies that either industrial output is rising as a share of GDP along with exports, or that exports account for a larger share of industrial output.

And if I had to bet, I would bet that exports share of industrial output is rising. Remember that consumption is falling as a share of GDP, so unless Chinese consumers are buying more goods and fewer services, domestic consumption of manufactured goods is falling relative to China’s GDP.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store