Now What’s That Got to Do with the Price of Oil?

This post was co-written with Peyton Kliefoth, an economics major at Northwestern University and research intern at the Council.

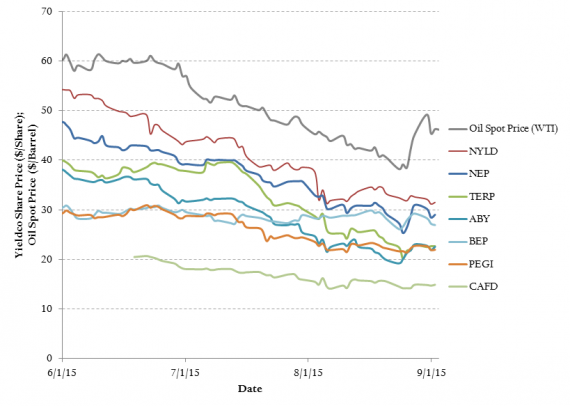

Over the weekend, I published a piece in Fortune Magazine explaining a surprising correlation between falling oil prices and tumbling shares of Yieldcos, which are publicly traded holding companies mostly comprising renewable energy assets in the U.S. and Europe (see chart below).

(NYLD: NRG Yield, NEP: Nextera Energy Partners, TERP: TerraForm Power (SunEdison Subsidiary), ABY: Abengoa Yield, BEP: Brookfield Renewable Energy Partners, PEGI: Pattern Energy Group, CAFD: 8Point3 Energy Partners (joint venture between SunPower and First Solar))

More on:

Fundamentally, the value of solar and wind projects should not depend on oil prices, since oil is rarely used in the developed world for electricity and therefore doesn’t compete with renewable power generation. It turns out that the cause of falling Yieldco share prices has less to do with what is being traded than who is doing the trading—I write:

Few paid attention to an ironic trend: the same investors holding oil and gas assets had also piled into an obscure but crucial class of renewable energy investment vehicles—so-called “Yieldcos”—driving down the financing costs of clean energy.

As it turned out, renewable energy prospects hitched to the conventional energy bandwagon hit a bump in the road. In June and July the bottom fell out of the oil market (again), the Fed strongly hinted at interest rate increases, and a number of renewable energy firms sought large sums from public capital markets. Together, these three unrelated developments conspired to spook fossil fuel investors, who dumped renewable energy Yieldco shares and plunged prices into a vicious downward spiral.

Now the stakes are high: if Yieldcos fail, renewable energy could lose access to public markets and the low cost of capital necessary to scale up wind and solar. To recover, Yieldcos may have to restructure, seek help from parent developer firms, and hope for constructive public policy to further de-risk renewable energy investments.

Whereas the article focuses on the causes of the recent downward spiral in Yieldco share prices and the remedies for stabilizing and lifting prices, in this blog post I’ll assess the underlying renewable energy industry and the long-term prospects for vehicles like Yieldcos. Even before the collapse of Yieldco share prices this summer, doomsayers predicted that Yieldcos were overvalued and went as far as to call the Yieldco model a “Ponzi Scheme.” To those analysts, this summer has vindicated their conviction that a Yieldco is no more than the sum of its parts, and that the stock market had erred in imputing value over and above the constituent renewable energy projects in a Yieldco’s portfolio.

More on:

I disagree. This summer certainly proved that Yieldcos, as currently structured, are unstable vehicles whose share prices are liable to spiral upward or downward without much of a change in the performance of the underlying projects. But if they can weather this perfect storm, restructure, and attract a broader investor base, Yieldcos can add considerable value by reducing transaction costs and providing public investors a diversified portfolio of renewable projects.

The renewable energy industry as a whole is doing very well right now. The costs of solar and wind projects have consistently fallen, and installed renewable capacity is growing around the world. But extrapolations that solar will account for thirty percent of the global power market by 2050 will not come true without further reductions in the cost of capital and participation from public markets, which can supply the scale of investment needed for renewable energy to rival conventional energy sources. That’s where Yieldcos come in.

How Yieldcos Create Value

There are three ways a Yieldco creates value over and above the value of the renewable energy projects it comprises. First, it reduces the risk of investing in renewable energy. To accomplish this, renewable energy developers spin off the least risky part of their portfolio—owning and operating renewable energy installations post-construction—creating a Yieldco, an independent, publicly traded entity. Thus, the Yieldco avoids the riskier elements of project development—regulatory approvals, construction, contracting—and only purchases operating or near operational assets from the parent developer that come with guaranteed revenues from long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) with utilities.

Second, Yieldcos offer public market investors—like institutional and retail investors—an easy way to invest in renewable energy; in other words, they reduce the transaction costs that would otherwise block public market capital in a sector dominated by private capital. This is possible because of the way Yieldcos return almost all of the revenue generated by renewable energy projects back to investors. Similar to Master-Limited Partnerships, which are holding companies for oil and gas infrastructure assets, Yieldcos are able to shield shareholders from double taxation, avoiding corporate income tax on renewable project revenues to distribute pre-tax dividends to shareholders. Since solar projects compose a majority of Yieldco assets, and solar panels require next to zero operating and maintenance expenditure, Yieldcos are able to return most (80–90 percent) of their projects’ operating revenue to investors through dividends.

The third way that Yieldcos add value—by promising 8–15 percent dividend growth—is what got them in trouble this summer. Yieldcos depend on high share prices to raise equity on public markets and purchase more renewable projects at returns that exceed their cost of capital, driving share prices up further. I call this a “treadmill of equity issuances and dividend payouts.” Unfortunately, the treadmill can overheat, and when share prices start to drop, they viciously spiral downward. I suggest that relying less on equity and more on debt—up to responsible credit limits—will enable Yieldcos to avoid spirals, though their share values will not be as high as when they were on the treadmill.

Still, even if Yieldcos are less aggressive about dividend growth, they add value to renewable energy projects by unlocking public capital markets through reduced risk and lower transaction costs. By focusing on developing a strong asset portfolio, Yieldcos can still play an important role in scaling up renewable energy.

Four Questions Underlying the Long-Term Success of Yieldcos

As Yieldcos mature and find ways to avoid short-term share price volatility, their long-term prospects will depend on macroeconomic fundamentals and the health of the renewable energy industry—these are far more logical factors to drive Yieldco value than the price of oil. There are four threshold questions that require affirmative answers for Yieldcos to succeed long-term:

Question 1: Will solar remain economical after the imminent expiration of the solar Investment Tax Credit (ITC)?

Yes. Although important in the near term to U.S. solar project economics, the ITC is not crucial to their long-term viability.

Currently, the ITC offers developers of U.S. projects 30 percent of the project value in tax credits through 2016 and 10 percent thereafter. The ITC was crucial to incentivize domestic deployment when solar economics were not so favorable, but today, installed solar costs are on a sufficient downward trajectory to make many projects viable on their own, without the tax credit. The expiration of the ITC will likely cause a drop off in project development in 2017, but falling costs will enable project growth thereafter. First Solar, a leading panel manufacturer, has projected highly competitive costs of $1 per installed Watt in 2017, without the ITC, and historically low bids in recent solar PPA auctions below 5 cents per kWh suggest that solar will be competitive in wholesale power markets even after the ITC step-down.

Yieldcos comprising solar assets should be able to weather this short-term storm, especially because many are amassing a global portfolio of assets, diversifying their exposure outside of the U.S. market.

Question 2: Can Yieldcos survive rising interest rates?

Probably. Rising interest rates will tarnish Yieldcos’ attractiveness as a low-risk, comparatively high return investment, but rates will have to rise considerably to really damage the Yieldco value proposition.

Yieldcos can be attractive because of the spread between the market’s “risk-free rate,” often defined as the yield on a ten-year Treasury Bill (about 2.13 percent today), and the Yieldco dividend yield, currently between 5–6 percent. However, the Federal Reserve has signaled that an interest rate hike is likely by the end of the year, possibly marking the end of a historically low interest rate era. Combined with the falling oil price, the Fed’s hints contributed to plunging Yieldco prices over the summer.

Still, rate hikes of a magnitude required to wipe out Yieldcos’ return over the risk-free rate are only distantly on the horizon. Michael Liebreich of Bloomberg New Energy Finance warns that if rates return to their 2007 level of 5.3 percent, Yieldco competitiveness as a low-risk investment would fall. Still, for the foreseeable future, modest interest rate hikes will likely not spell doom for Yieldcos.

Question 3: Is there room for growth?

Yes, resoundingly. The growth potential of renewable energy in the United States and the world is so high that Yieldcos will not run out of projects to acquire anytime soon.

A useful point of comparison is the Yieldco’s cousin, the oil and gas asset MLP. MLPs support around 10 percent of the $1.1 trillion U.S. oil and gas sector and have posted an annualized 27 percent growth in market cap over the last 24 years. By contrast, Yieldcos represent less than 1 percent of the burgeoning renewable energy project finance sector, and Yieldco dividend growth targets are considerably less ambitious at 8–15 percent. Fundamentally, there is certainly room for growth.

Question 4: Is a Yieldco all that different from a Ponzi Scheme?

Yes. Although a Yieldco does depend on continually raising equity to acquire projects and pay shareholders, it is not a Ponzi scheme, because it comprises real, income generating assets just as do other established financial vehicles. However, it is unclear if the accounting practices that enable Yieldcos to distribute high dividends are sustainable.

Unlike a Ponzi scheme, in which new cash is raised to pay existing investors, a Yieldco actually invests new cash in income-generating assets en route to paying dividends. Some may quibble that the difference with a Ponzi scheme is semantic, but the Yieldco model is akin to MLPs and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), both of which are considered established, sound investment vehicles. To call one a Ponzi scheme would be to indict all three models.

However, questions remain unanswered about the details of Yieldco accounting. In particular, Yieldcos assume a very low rate of depreciation oftheir operating assets, of which solar installations are often the majority. Since the installations have historically proven to be long-lived, in some cases twice as long as the standard twenty-year PPA contract signed with utilities, Yieldcos only deduct a small “Maintenance” sum from their operating revenues before distributing dividends to shareholders. If this assumption is wrong, however, then Yieldcos will have failed to accurately depreciate their assets, so that over time their asset base shrinks because of inadequate reinvestment and excessive dividend distributions.

It will be years and perhaps decades before Yieldco claims of asset life are vindicated or disproven. In the meantime, critics will continue to accuse Yieldcos of hiding the need to reinvest in capital expenditure in order to reward shareholders. But the historical record of long-lived and productive renewable energy projects is on the Yieldcos’ side.

In summary, Yieldcos do add value to the projects that they bundle together, and the health of the renewable energy sector can underpin Yieldcos’ long-term success. That means that the conclusion I wrote to the short-term story of Yieldco prices tumbling alongside oil prices applies equally well to the long-term story of how the future of renewable energy may depend on the success of Yieldcos:

Renewable energy is on the cusp of becoming a mainstream alternative to fossil fuels—getting there requires a mainstream financing tool. Although the Yieldco model must improve after derailing this summer, getting it back on track is in everyone’s best interest.

Online Store

Online Store