Russian Contagion, Geopolitical Risk, and Markets

More on:

Yesterday, I published my Global Economics Monthly. I argue that further economic sanctions against Russia would have significant global economic effects because of the Russia’s connectedness to energy and financial markets. Why then, are markets apparently so sanguine? Is it because investors, by and large, expect de-escalation? Is it a view that Russia does not matter for the global economy? Could it be a search for yield? Or is it the inherent difficultly that markets face in pricing in hard-to-quantify, large geopolitical dislocations? Probably a little bit of all of the above.

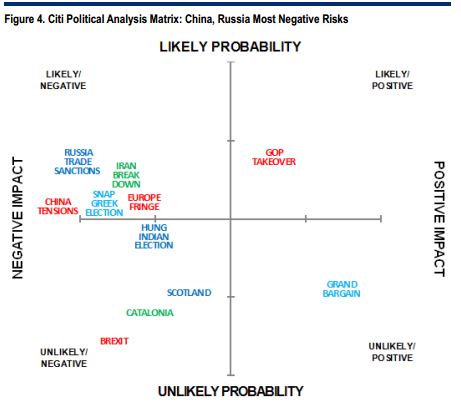

A poll of investors by Citigroup’s Matthew Dabrowski and Tina Fordham illustrates the problem even if it doesn’t answer these questions. The survey of over 1000 investors reported significant concern about political and security risks in Russia, China, and Europe this year. In addition to sanctions, these risks included a breakdown in Iran nuclear talks, victories by fringe parties in European elections, snap elections in Greece, and Sino-Japanese military tensions sanctions. Russian trade sanctions and China tensions were seen as having the most negative impact (see their chart below), but markets remain constructive at the same time, “raising the question of whether market participants have fully considered these geopolitical risks.”

Source: Citigroup

David Gordon at Eurasia Group also sees a disconnect between the two worlds: the political and the markets-based. He contrasts rising geopolitical concerns with the generally constructive mood among investors at the recent IMF-World Bank spring meetings as well as strong (and not-terribly volatile) markets. He is more comfortable than I am that markets have it right: “geopolitics is not quite the nightmare some seem to think. Markets don’t always have it right, but their current perspective on the big picture remains pretty close to the mark.” He does agree, though, that on Russia in particular, markets do seem too sanguine.

What does this mean for our sanctions policy towards Russia? Up till now, it does appear that vulnerability of Western companies to sanctions and possible retaliation has been a brake on the Obama administration’s willingness to move aggressively ahead with financial sector (“sectoral”) sanctions. But that may be changing. There is a growing recognition that the chill of potential sanctions has not been an effective constraint on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, and perhaps frustration that markets have not reacted more. (Though my market friends emphasize it is hard to derisk in this environment, particularly for large emerging market portfolio investors facing shrinking liquidity.) There is a sense now in Washington, D.C. that markets have been warned and have had time to adjust.

Financial sector sanctions are not a zero-one decision, as they could in principal be targeted at certain transactions and relationships to try and manage the fallout for the West. But sectoral sanctions seem to me the most likely scenario. The continuing disconnect between D.C. and New York suggests markets could correct sharply if conditions on the ground in Ukraine worsen.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store