Secrets of SAFE: A sharp slowdown in reserve growth and large “hot” outflows in q4….

More on:

China’s formal foreign exchange reserves rose by about $40 billion in the fourth quarter, rising from $1906 billion to $1946 billion. Adjusted for valuation changes, that works to a $55 billion or so increase. But appearances can be deceiving.

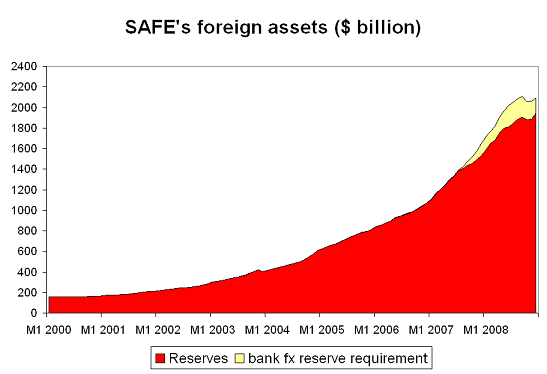

In the past, China “hid” the pace of increase in its reserves by forcing the banks to hold dollars as part of their required reserves. Those dollars showed up on the PBoC’s balance sheet as “other foreign assets” but weren’t counted as part of China’s formal reserves. In the fourth quarter, China’s reported reserves overstate its true reserve growth, as the banks reserve requirement was cut. That led to a $26 billion fall in the PBoC’s other foreign assets in October and, I assume, a comparable fall in December. Given the size of the reduction in the reserve requirement in December, that is conservative.*

That means that the PBoC’s “true” reserves didn’t grow at all in the fourth quarter, best I can tell.

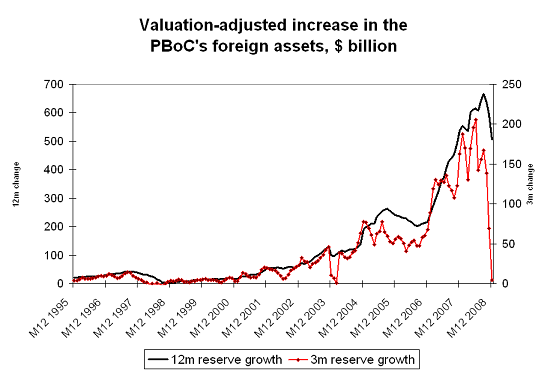

Valuation changes had a fairly modest impact on the data for the quarter as a whole, but a huge impact on the data for individual months. They pulled reserves down in October and pushed reserves up in December. Both effects were quite significant – in the $50 billion range. That has one big implication: China was adding to its reserves (if reserves are defined broadly to capture the PBoC’s other foreign assets) in October but not in December. My best guess is that China added about $15-20 billion to its reserves in October, another $10 billion in November and lost $20 billion in December. My numbers are a bit different than those of Morgan Stanley’s Wang Qing. He believs capital outflows peaked in October. I would put the peak in December -- which incidentally implies that the small RMB devaluation that China tried in early December had a big impact on capital flows.

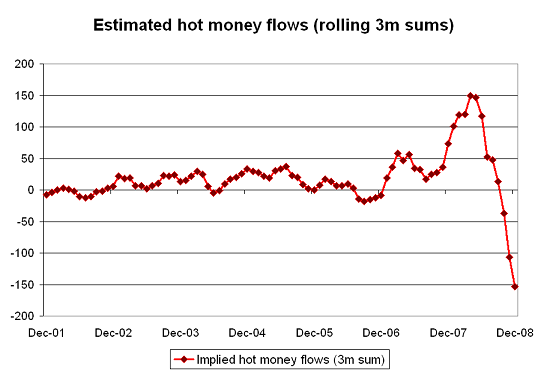

I wouldn’t put too much emphasis on the monthly estimates though. Combine China’s huge reserves and large moves in the currency markets and you get large valuation changes. If my estimate of the currency composition of China’s reserves is off, my monthly estimates will be a bit off too. The trend though is clear. Chinese reserve growth looks to have peaked earlier this year.* On a rolling 3m basis (adjusting for valuation changes and likely changes in the PBoC’s other foreign assets), Chinese reserve growth has essentially stopped.

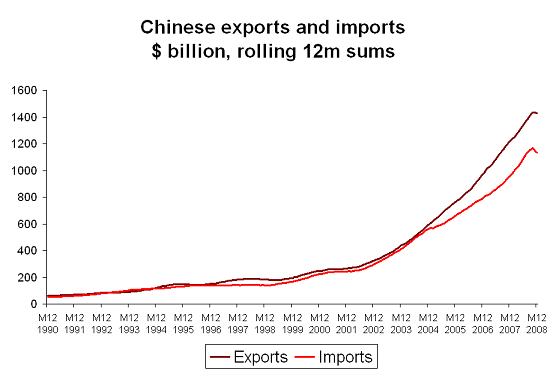

The sharp fall in the pace of reserve growth is at odds with the trend in the trade data. Exports are now falling – but imports are falling faster. Some of the fall in imports is in anticipation of future falls in exports (no need to import components), some reflects a fall in commodity prices but some also reflects a fall in China’s domestic demand. Y/y imports from the US and Europe were down in November – and that isn’t because China imports a lot of components or commodities from Europe.

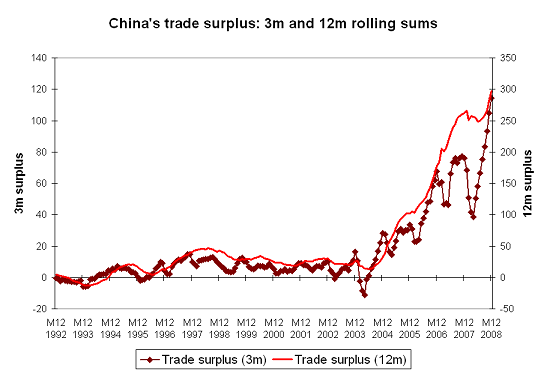

As a result, China’s trade surplus is rising – China’s fourth quarter surplus set a record ($114 billion), and its surplus for all of 2008 topped its 2007 surplus. Given that oil averaged $100 in 2008 – well over its 2007 average – that indicates that for much of the year export growth was much stronger than import growth.

There is only one way to square a record trade surplus with the sharp fall in reserve growth:

Hot money is now flowing out of China. Here is one way of thinking of it:

The trade surplus should have produced a $115 billion increase in China’s foreign assets. FDI inflows and interest income should combine to produce another $30-40 billion. The fall in the reserve requirement should have added another $50-55 billion (if not more) to China’s reserves. Sum it up and China’s reserves would have increased by about $200 billion in the absence of hot money flows. Instead they went up by about $50 billion. That implies that money is now flowing out of China as fast as it flowed in during the first part of 2008.

And in December, the outflows were absolutely brutal. December reserves were up by $20 billion or so after accounting for valuation changes – but the fall in the reserve requirement alone should have pushed reserves up by at least $25 billion. Throw in a close to $40 billion trade surplus and another $10 billion or so from FDI and interest income, and the small increases in reserves implies $70 billion plus in monthly hot only outflows … That’s huge. Annualized, it is well in excess of 10% of China’s GDP. Probably above 15% …

No wonder the PBoC is worried about unusual swings in capital flows.

China can absorb such a swing in capital flows better than most. And in some sense the outflows now just represent a reversal of earlier inflows, not a broad based movement of funds out of China. But it does still highlight that China’s controls are porous –

In one sense this is good – it makes it harder for China to engineer a controlled depreciation against the dollar. And that may mute internal calls for China to prop up its exports with a depreciation. China presumably doesn’t want to create perception that the renminbi is a one way bet down after it was long considered a one-way bet up. Andrew Batson of the Wall Street Journal:

The threat of outflows, analysts say, appears to have kept China from significantly depreciating its currency, despite pressure from exporters for a cheaper yuan. Chinese exporters are suffering from a decline in demand in the U.S. and Europe, and a less valuable yuan would help make their goods more attractive. A brief downward push in the yuan’s value in early December was met with panic selling in the foreign-exchange market, but since then, the central bank has held the yuan around 6.85 to the U.S. dollar.

"If they engineer a depreciation it may change the expectations not only among foreign investors, but also among China’s own residents," thereby encouraging ordinary people to send money abroad en masse, said Wang Qing, an economist for Morgan Stanley. Indeed, investors have been steadily reversing bets on gains in the currency: Yuan bank deposits in Hong Kong, for example, have been falling every month since June. Reluctance in Beijing to weaken the yuan from current levels is largely welcome news for China’s neighbors and trading partners. They have worried that a weaker yuan could start a cycle of competitive devaluations that would worsen the current global economic woes.

And so long as China’s exports are holding up better than the world’s imports – and China’s surplus is rising – there isn’t a fundamental case for a depreciation either. There is by contrast a strong case for a bigger domestic stimulus -- that would help China and help China’s neighbors by helping to bring China’s surplus down, or at least keep it from rising. See the World Bank’s David Dollar.

What of Chinese purchases of US treasuries – a hot topic last week. Slower Chinese reserve growth implies reduced purchases of Treasuries, right?

Umm, no.

We don’t have the November or December TIC data yet, only the October data. But so far there is no evidence that slower reserve growth has translated into reduced Treasury purchases or reduced dollar purchases. Consider a graph of the average increase in China’s reserves over the last 3ms v China’s average purchases (using the Setser/ Pandey adjusted data series which tries to capture flows through London)

What is going on? Well, China is clearly increasing the Treasury’s share of its portfolio by shedding risk assets. And the strong rise in the China’s dollar holdings?

That may be a bit deceptive. My best guess is that China has pulled funds from private fund managers and private custodians and parked those funds in short-term Treasuries. That would explain why the TIC data is suddenly capturing huge flows from China. It is just a hunch though …

Over time, if hot money outflows subside, China’s reserve growth should converge to its current account surplus (plus net FDI inflows). That implies ongoing Treasury purchases – though not at the current pace – barring a shift back into “risk” assets. And if hot money outflows continue, watch for Hong Kong and Taiwan to buy more Treasuries. The money flowing out of China doesn’t just disappear … it has to go somewhere.

UPDATE: Nick Lardy of the Peterson Institute believes China shifted foreign exchange from the PBoC to ABC in q4 to help with the recapitalization of ABC. If that is true, this would help to explain the modest reserve growth. It thus implies more modest hot money outflows. To have an impact on reserve growth, this would need to be funds that haven’t already been shifted to the CIC. There is no doubt that the CIC injected some money into the CIC. The question is whether or not SAFE did too, and whether or not the CIC was using funds that were transferred to the CIC long ago or more recently. If anyone has useful details, I am all ears.

* Logan Wright of Stone and McCarthy is on the case; he should have a definitive estimate soon.

** This chart shows the change in the foreign assets that appear on the PBoC’s balance sheet. It doesn’t try to adjust for funds shifted to the banks in 2003 (the recapitalization of BoC and CCB) or the funds shifted to the banks in 2005-06 (ICBC recapitalization, the use of swaps to allow the banks to manage a portion of the PBoC’s reserves) or the funds shifted to the CIC in late 07 and q1 08. I’ll have a post going through all this data in great detail soon.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store