Sequester, Day 1

More on:

Does today feel different? Did the earth shake? Packing your lunch rather than buy out?

Welcome to the sequester.

Another manufactured fiscal crisis has failed to produce smart policies. The effects of this failure will take time to be felt, a “slow ripple of pain” as Politico puts it in their note on the timing of the cuts. Furloughs notices have to be sent out, agencies will try and smooth or delay the disruptions to services, and no doubt some of the dire warnings are overdone. But by April we would see material disruptions to services. That fact, plus rising public unhappiness, makes the sequester unsustainable on economic or political grounds.

The next cliff, the March 27 continuing resolution (CR) funding the government, provides a good opportunity to address the sequester, either by providing greater flexibility to the administration in applying the cuts or by backloading and replacing the cuts with other measures. If the CR fails to address it, the debate could spill into April or May, when the dislocations from layoffs and cutbacks become more critical and perhaps even bring the debt limit debate back into play.

How big a hit?

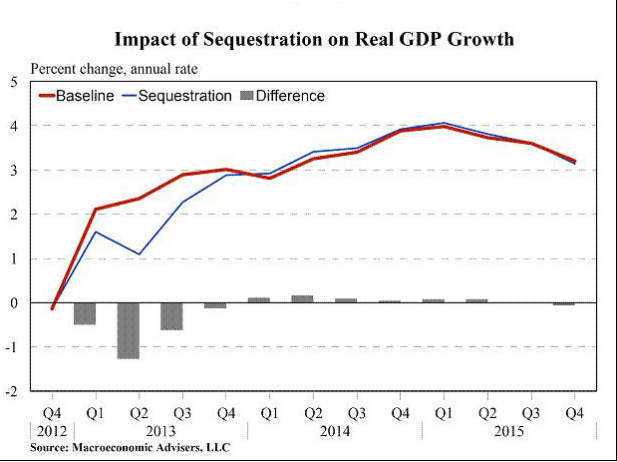

The $85 billion in cuts for FY13 that go into effect today will reduce discretionary appropriations to below 2008 levels. Defense programs will be cut 13 percent and affected non-defense programs by about 9 percent. Because these are cuts to budget authority and some programs pay out over several years, the direct effects on government spending this fiscal year will be smaller, around $45 billion. Macroeconomic Advisers, in a well-publicized and detailed study, estimated the sequester would cut GDP by 0.6 percent of GDP for 2013 (to 2 percent). By the end of 2014, the sequester would cost 700,000 jobs and raise the unemployment rate to 7.4 percent. The Fed would delay tightening.

On one level, this seems manageable in a $16 trillion economy, relative to the warnings that have preceded it. However, it’s hard to account for the effects of a broader disruption in the provision of basic services and public goods. Long waits for planes, delays in food inspection or medical services, and the like could disrupt activity to a far greater degree than these estimates suggest.

Markets appear to have responded to the onset of the sequester by…ignoring it. Recent volatility has reflected renewed fears for Europe in the wake of Italian elections, uncertainty about Fed policy, and currency wars. It’s hard to pinpoint an independent sequester effect. Perhaps this reflects cynicism that Congress will find a way to kick the can. Perhaps, instead, it’s "cliff fatigue".

Nonetheless, it’s hard not to conclude that the series of endless fiscal cliffhangers is beginning to have an effect on activity. Recent surveys show consumer confidence has been affected, and business investment delayed, due to uncertainty about fiscal policy.

What next?

I have previously written that the window for a grand bargain is closing. Each previous effort has fallen short, leaving scar tissue and distrust that make it more difficult to negotiate the next time. In addition, the deficit reduction that we have achieved may be taking the pressure off our leaders to deal comprehensively with our fiscal deficit.

Three years of fiscal showdowns have produced around $2.7 trillion in budget savings, primarily through new revenue and cuts to discretionary spending programs. CBO now expects the fiscal deficit to fall below 4 percent next year, and to 2 1/2 percent in FY15. While this is not enough to fix our long-term fiscal problem, it is enough to stabilize the debt at a little over 70 percent of GDP for the next several years before rising interest rates, an aging population and rising medical costs cause the debt to again rise.

I continue to hope that a grand bargain can be reached that addresses entitlements, tax reform and the other fundamental drivers of deficit. It would be far better to address the problem now rather than later when a market revolt or the inescapable math of our fiscal problem produces a crisis. But if that is not possible, it may be time to recognize that fact and find a way to defuse the sense of constant fiscal crisis. Let’s fight over immigration, gun control and other key priorities. We need an exit strategy.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store