More on:

This is a guest post by Jacob Zenn, an analyst of African Affairs for the Washington D.C.-based think tank, The Jamestown Foundation, and a contributor for the West Point CTC Sentinel.

After Boko Haram launched major attacks on the rural border towns of Baga, Monguno, Bama, and Marte in Borno State, in April and May, Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in Borno and neighboring Adamawa and Yobe states on May 14, 2013. Soon after, more than two thousand Nigerian troops were deployed to Borno, which shares borders with Cameroon, Chad, and Niger.

Despite hype about the “massive troop deployment,” so far the operation seems rather restrained. The Nigerian army, which often over-reports its successes and under-reports its casualties, claims to have arrested only about one hundred Boko Haram militants in the first two weeks of the operation—a relatively low number compared to the several thousand Boko Haram members in the region. Information is hard to obtain from Borno because the government shut down cell phone service; there have been few reports of extra-judicial killings like in July 2009, when Boko Haram founder Muhammad Yusuf and a thousand other members were killed by the security forces. However, there have been contrasting narratives to government reports about defeating Boko Haram and avoiding civilian casualties.

It is in the interest of the United States, which offered Nigeria security assistance to combat Boko Haram in 2012 and provided border surveillance equipment in 2013, that Nigeria carry out an effective and lawful counter-insurgency campaign. As Secretary of State Kerry said on May 17, human rights violations could “escalate the violence and fuel extremism.” In my opinion, it could also damage U.S. AFRICOM’s “still undefined” future role and reputation in Africa because of AFRICOM’s assistance to the Nigerian military.

In addition, the United States is already a main part of Boko Haram’s anti-secular, anti-Christian, anti-democracy, and anti-Western narrative, which Abubakar Shekau briefly describes in a rare English diatribe at 19:30 in a video from January 2012. Shekau has also called President Obama a “terrorist in the afterlife,” promised America that “jihad has begun,” and mentioned the United States more than any other country. This is likely because of the large U.S. influence in the country, from “Nollywood” to democracy and presidential elections “patterned” after the U.S model. U.S. interests could face additional threats in West Africa if the United States is associated with abuses of its allies.

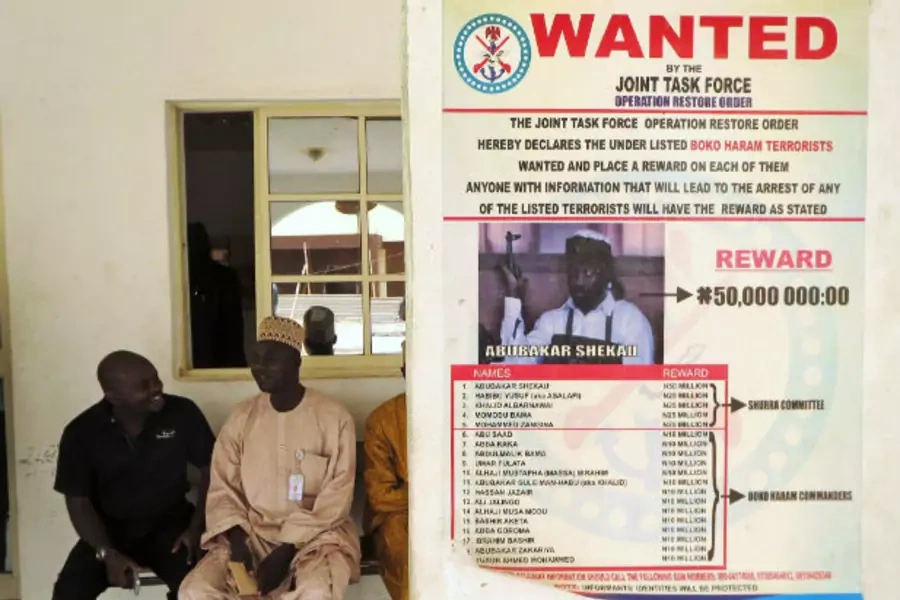

On June 3, the United States announced a U.S. $7 million reward for Shekau’s location. This is more money than for Mokhtar Belmokhtar or Oumar Ould Hamaha, whose respective groups, “Signatories in Blood” and Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, jointly claimed responsibility for attacks in Arlit and Agadez, Niger on May 23. There are also rumors in Nigeria that the United States is seeking to eliminate Shekau in a drone strike from its new base in Niger. Meanwhile, Boko Haram members carried out an attack on prison guards in Niamey, Niger on June 2, but failed to escape.

The United States is becoming closely involved operationally–and in terms of local perceptions–to the regional security architecture in Nigeria and West Africa. As such, the U.S. strategic footprint in Africa is going to be tied to the actions of its older strategic partners, such as Nigeria, and newer allies, such as Niger.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store