U.S. Universities Dominate World Rankings, For Now

The new college rankings are out. No, not the rankings for football prowess (though they are out too). The Times Higher Education World University Rankings. They debuted last week, and American higher education has reason to chant, “We’re Number One!” The question, though, is for how long?

Now university rankings should always be taken with a grain of salt for anything other than establishing broad trends. For example, I don’t know any University of Virginia graduate who thinks that UVA (#118) ranks behind the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (#42), let alone nearly every school in the Big Ten (which oddly enough has a dozen members). The reality is that universities have different strengths and weaknesses, and there’s no sure way to measure either. Even if there were, it’s not obvious whether great strength in, say, engineering should count more, the same, or less than great strength in the physical or social sciences. Throw in the differences across borders in terms of teaching formats and approaches, and global college rankings are a dicey enterprise.

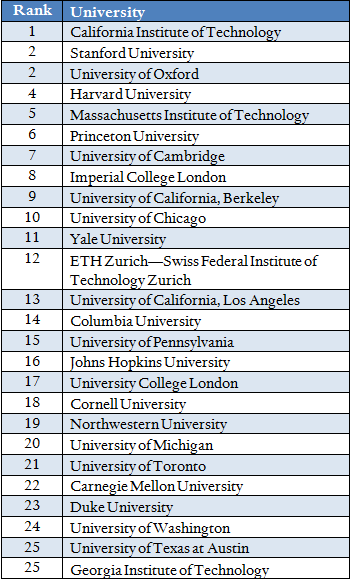

That said, here is the world top 25:

That’s an impressive showing for U.S. universities. They take seven of the top ten spots, eleven of the top fifteen, fifteen of the top twenty, and twenty of top twenty-six spots. (Georgia Tech and The University of Texas at Austin—UT asks that you capitalize “The”—are tied for twenty-fifth.) Overall, the United States accounts for seventy-six of the top two hundred universities in the rankings.

Much of the coverage of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings has trumpeted how universities in the West have lost ground to their counterparts in Asia. The British universities in the top two hundred slipped an average of 6.7 places compared to their ranking last year. Meanwhile, fifty-one of the top seventy-six American universities lost ground in the ratings.

The improved ratings for Asian universities, and especially Chinese and Indian universities, are to be expected. The rise of China and India as economic powerhouses makes it almost inevitable that their institutions of higher learning will become powerhouses as well. Indeed, Beijing is actively seeking to create the Chinese version of the U.S. Ivies, the so-called C9 League. These nine super-institutions recently received $270 million each from the Chinese government. That kind of money can buy a lot of bricks and books.

But Chinese and Indian universities still have a long way to go before they can to match the best in the West. The highest rated Chinese university is Peking University, which clocks in at #46. Next is Tsinghua University at #52. (The University of Hong Kong stands at #35, but its history is quite different from mainland Chinese universities.) No other Chinese or Indian university is in the top two hundred. Elite status requires not just money but time and a lot of effort.

The real threat to Western, and specifically U.S., universities comes not from Asian universities flush with cash but from eroding support at home for investing in top-flight universities. California’s budget woes have rocked the world’s greatest single higher education system; five University of California campuses rank in the Times Higher Education’s top fifty but their budgets are being slashed. The flagship universities in Georgia, Illinois, Texas, and Virginia (among others) face tough choices about how to maintain academic excellence as state support shrinks in relative (and sometimes absolute terms) and the pressure to hold down tuition increases. Whether states choose to continue investing in their colleges and universities, and whether students can find ways to finance their college educations, will go a long way to determining how competitive the United States remains in a global economy.

One final point. The focus on how many universities each country has in the top fifty or hundred misses what may be the most profound trend in U.S. higher education, namely, that U.S. universities are becoming far less “American” and far more global in their makeup. The “multinationalization” of the faculties of American universities has long been evident to students taking math and science courses. But increasingly it describes the student themselves. Nearly one-in-four Columbia University and Stanford University students are international students, as is one-in-five Northwestern students and one-in-seven UC-Berkeley and University of Michigan students. So the simple fact that a student goes to class in Palo Alto, Evanston, or Ann Arbor says increasingly less about which national economy will capture the benefits of his or her higher educational attainments.

Online Store

Online Store