Will Piekos: China’s Inroads into Central Asia

More on:

Will Piekos is a research associate for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

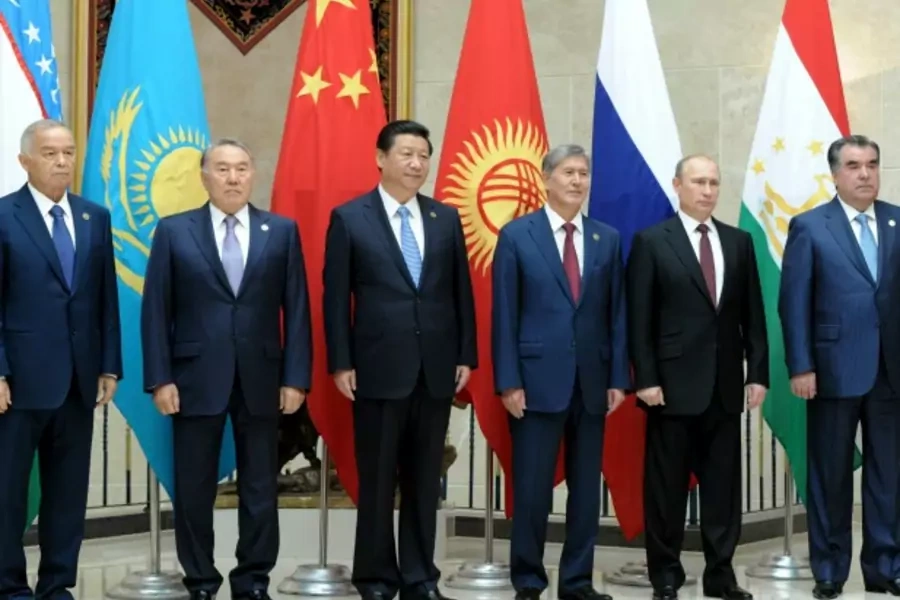

Chinese President Xi Jinping wrapped up a lengthy trip to Central Asia this past weekend that ended in a meeting of the six-member Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Bishkek, Krgyzstan. On paper at least, the trip was a significant success for Beijing. Xi signed multiple economic and energy agreements with the former Soviet satellite states and showed regional security leadership through the SCO. The trip even included some attempts at soft power projection—Xi announced 30,000 government scholarships to students of SCO member states. With the United States withdrawing from Afghanistan, Central Asia is an area full of potential for Chinese investment and diplomacy.

On the economic and energy front, China made substantial progress in locking down Central Asian resources. In Turkmenistan—the only ‘Stan that is not a member of the SCO—Xi inaugurated production at Galkynysh, the world’s second-largest gas field. China also announced $30 billion in deals in Kazakhstan, including CNPC’s $5 billion stake in the Kashagan offshore oil project. And in Uzbekistan, Xi and his hosts revealed $15 billion in oil, gas, and uranium deals. Though it would be premature to pronounce these deals as successes, they represent a commitment by Beijing to invest more in the region. Chinese investment is enticing to Central Asian regimes in part because Beijing doesn’t impose restrictive trade policies to investment (like Moscow) or promote democratization and respect for human rights (like Washington). Russia still controls the majority of the region’s energy exports, but Beijing has made impressive advances into the region, securing land-based access to oil and natural gas and alleviating some of its resource security concerns.

At the regional security level, China earned the reaffirmation of the SCO’s fight against the “three evil forces”—terrorism, separatism, and extremism. Beijing fears Uighur unrest in the far western province of Xinjiang, where Han Chinese have faced sporadic violence from separatists and Uighurs angered by what they see as efforts at Sinification. A report just this week revealed that Chinese security forces had killed twelve Uighurs and wounded a score at a “terrorist facility” in an area near the Chinese border with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. As the United States withdraws troops and military aid from the region, Central Asian leaders fear extremist elements will turn to the northwest in search of a new fight, while Beijing worries that terrorism in these states will bleed into Xinjiang and encourage Uighur separatists. They hope the SCO can fill the gap left by the U.S. withdrawal.

China’s leadership in the SCO also allows Beijing to gather consensus around foreign policy objectives further away from home. During the meeting, the SCO unsurprisingly took positions consistent with Chinese (and Russian) views. These included condemning the possibility of military strikes or unilateral sanctions against Iran (which is an observer at the SCO), stressing the importance of negotiations in maintaining peace on the Korean Peninsula, and opposing Western intervention in Syria. And there has been a certain convergence in China and Russia’s policy agendas—most notably an anti-Western, anti-U.S. stance on the previously mentioned issues—that have allowed the two countries to work together in Central Asia and in the SCO. Meanwhile, the authoritarian nature of the other SCO regimes—and their dependence on China and Russia for investment—means that the organization often speaks with one voice.

This is not to say that Beijing does not face obstacles in its efforts to “go west.” Investment by Chinese companies and the importation of Chinese labor faces some of the same resentment and accusations of cultural imperialism that Chinese companies encounter elsewhere in their “going out” strategy. The “three evil forces”—and the social conditions that inspire them—are notoriously difficult to stamp out, especially in impoverished areas ruled by undemocratic regimes. China’s energy deals with Central Asian nations will undoubtedly help the region’s autocratic regimes, but if the benefits don’t trickle down to the people, China could find itself the target of popular demonstrations. Moreover, China will have to shoulder a bigger security load in the region and coordinate multilateral operations, with which the PLA has minimal experience.

With foreign policy challenges on many of its other borders—most recently tensions in the East and South China seas and a border dispute with India—Beijing has the opportunity for economic and diplomatic success in Central Asia. The question is, will China fight only for its own interests, or will it put those of its smaller neighbors on similar footing? For now, at least, the two are in step.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store