As Ye Sow: Obama Harvests the Fruits of UN Engagement

More on:

This piece was originally posted on CNN.com here.

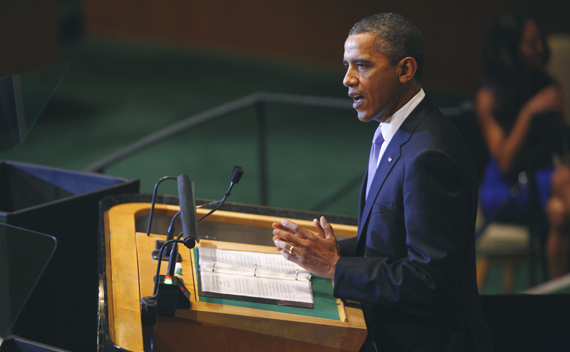

In his eloquent address to the opening session of the United Nations General Assembly, President Obama outlined an optimistic vision for a world without war, though his treatment of important issues like Palestine fell short. For nearly seven decades, the UN has struggled with the overriding objective to pursue peace in an imperfect world. Yet, President Obama argued that the world is closer than ever before to realizing that goal, thanks not to the balance of power but concrete steps to advance human dignity, security, and prosperity.

“Peace is hard”, the President repeatedly reminded his audience. But it is within our grasp. “The tide of war is receding,” as the United States draws troops down in Iraq and Afghanistan. The death of Osama bin Laden and the degradation of al Qaeda have reduced the threat of transnational terror. The demands for freedom that have “lit the world from Selma to South Africa” have now “come to Egypt and to the Arab World,” he proclaimed. Now, the President contended, “We stand at a crossroads of history with a chance to move decisively in the direction of peace.”

For an administration regularly pounded for being AWOL on human rights, Obama’s speech placed surprising emphasis on the fundamental human aspiration for freedom as the driving force of global change and the UN as ultimate guarantor of enduring peace. The President celebrated the world’s “extraordinary transformation” during 2011. Over the past year, the international community has supported the cause of human freedom in dramatic ways. It has shepherded the peaceful independence of South Sudan; supported non-violent political transitions in Tunisia and Egypt; and authorized military interventions to topple enduring dictators in Cote D’Ivoire and Libya. “This is how the international community is supposed to work,” the President declared, “nations standing together for the sake of peace and security; individuals claiming their rights.”

The President made a convincing case that oppression, insecurity, and poverty are the ultimate causes of violence in the twenty-first century. Like the father of the United Nations, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Obama understands that enduring peace depends on ensuring freedom from fear and freedom from want for the peoples of the world.

What the President failed to do was to persuasively account for the many inconsistencies in U.S. efforts to advance human freedom and dignity around the world—or to offer alternative paths when the United Nations responds weakly to glaring atrocities. The President’s toughest moment came in explaining the U.S. stance on Palestinian statehood. As expected, he insisted the only true route to Middle East peace—and secure Palestinian statehood—must come through direct bilateral negotiations with the Israelis. “There are no shortcuts,” he insisted. But the overall message was incongruous, after his previous paeans to democratic self-determination in the Arab world. And it surely fell on deaf ears, given Palestinian impatience with Israeli obstruction, notably on settlement issues.

At this stage, Palestinian leaders feel they have little to lose from seeking statehood and the legitimacy that accompanies it. The President gave them few reasons to desist in this effort. The administration hopes to delay a Security Council vote on statehood indefinitely, to avoid casting a U.S. veto. But the Palestinians have another route to advance their aspirations—through the UN General Assembly.

Nor did the President provide any indication of how the United States intends to proceed on Syria, where the regime’s atrocities have exceeded those committed by Qaddafi—but without triggering the vigorous UN sanctions (much less armed intervention), given Russian veto threats. Obama was left with the toothless phrase, “Now is the time for the United Nations Security Council to sanction the Syrian regime, and to stand with the Syrian people.” He could have sharpened this demand considerably by explicitly calling on Moscow (and Beijing) to authorize a robust sanctions effort against the government of Bashar al-Assad—or at a minimum abstain from such a resolution.

President Obama concluded his speech with passing references to various other pressing issues. He called on the membership to “insist on unrestricted humanitarian access” in the Horn of Africa, but without proposing concrete action to ensure that this occurs. He entreated the membership to “build on the progress made in Copenhagen and Cancun,” without specifying which commitments should take priority. More substantially, he proposed increased international cooperation to give the World Health Organization the capabilities it needs to meet emerging threats to bio-security, both natural and man-made.

But the most striking aspect of Obama’s speech was less such particulars than its ethical and moral tone. In the president’s mind, world peace depends on the global advance of liberty, equality, and justice. And “though there is no straight line to progress, no single path to success”, he left no doubt that, in his mind, the world is on the right track.

The President closed by recalling what Harry Truman had said when the cornerstone of the UN’s headquarters was being put in place: “The United Nations is essentially an expression of the moral nature of man’s aspirations.” While one may admire Truman’s (and Obama’s) idealism, the intervening seven decades have shown just how hard it can be for the United Nations—or any other international body—to fashion moral results from humanity’s crooked timber.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store