The Pacific Islands are of intensifying geostrategic interest. Sitting between Asia and the Americas, the region is one of the world’s most dependent on aid. It acts as the custodian of large swaths of the world’s fisheries and makes up a significant voting bloc at the United Nations, giving the region more geostrategic relevance than its modestly sized population might suggest. With China expanding its foreign aid programs in the region, the geopolitical competition for influence among China and other international and regional powers appears to be heating up. However, recent data from the Lowy Institute’s Pacific Aid Map finds that China’s aid pledges tend to be overstated. Additionally, Australia and New Zealand remain leading donors.

The Challenges

The Pacific Island region encompasses a population of thirteen million people, spread across twenty to thirty thousand islands and twenty-two countries and territories that make up 15 percent of the Earth’s surface. The remoteness and small size of these countries, with the exceptions of Fiji and Papua New Guinea, restrict most of them from progressing along conventional economic growth paths. Natural disasters and climate change are further impediments to human development. Compounding these factors, the region’s population, already facing a significant youth bulge, is expected to grow by 49 percent in the next quarter of a century.

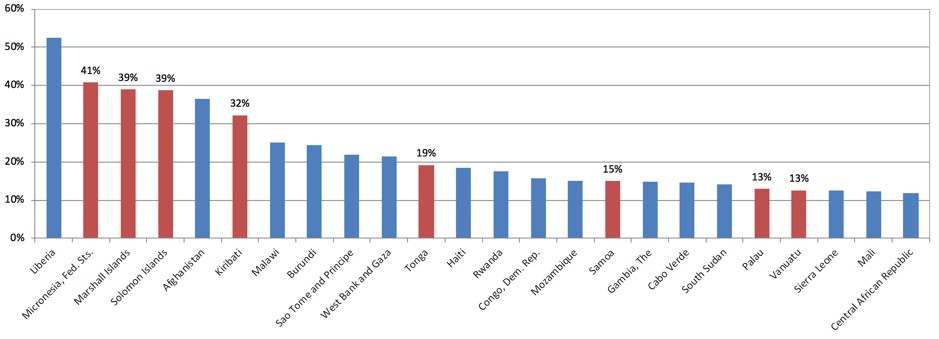

Top Twenty-Five Aid-Dependent Countries and Territories (aid as a percentage of gross national income, 2011–2013 average)

Source: World Bank

Such challenges have generated aid dependency. Because aid is important to the well-being of the Pacific Island region, its effectiveness deserves close scrutiny.

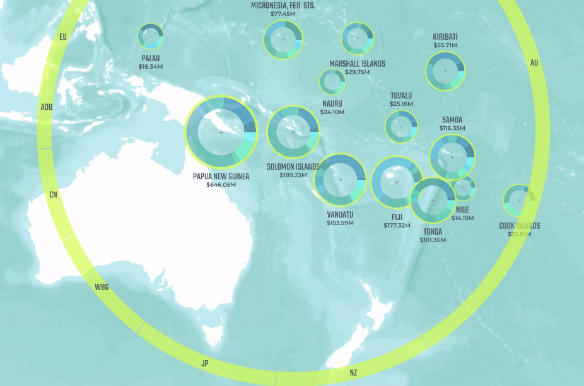

In any given year, close to $2 billion in aid is invested in the Pacific Island region by at least sixty-two bilateral and multilateral donors, not including hundreds more nongovernmental organizations and private foundations. Public information at the project level for all donors is often sparse, lacks detail, and is difficult to access.

A lack of transparency can hamper the effectiveness of coordinating aid efforts, exchanging ideas and best practices, assuring accountability, and aligning aid with a country’s own investment priorities, especially in smaller countries where bureaucracies are spread thin. For example, the twelve-person Ministry of Finance and Economic Development in Kiribati is expected to oversee more than three hundred aid projects from over twenty donors, on top of managing the country’s finances.

It is for these reasons that transparency has been enshrined in international high-level aid effectiveness agreements, including the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness [PDF], the 2008 Accra Agenda for Action, and the 2011 Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation [PDF].

While the goal of the Pacific Aid Map is to make aid better in the region, it also helps to inject nuance into an intense public debate about aid.

A New Strategic Landscape

The Pacific Island region is Australia and New Zealand’s immediate neighbor, critical to both their national and reputational interests. Further abroad, the region is custodian of major fisheries deposits, makes up a significant voting bloc in the United Nations, and is on the frontline of climate change vulnerability. Recently, in an address to the Lowy Institute, Samoan Prime Minister Tuilaepa Malielegaoi noted that “geo-strategic competition between major world powers has once again made our region a place of renewed interest and strategic importance.”

The growth of China’s presence in the region has been well documented. Between 2006 and 2016, China committed close to $1.8 billion in foreign aid from an almost nonexistent base in the ten-year span before 2006. Its aid program, 70 percent of which comes in the form of concessional loans, has been used as a vehicle to spread its community and commercial interests throughout the region. At the same time, China has been accused of engaging in debt-trap diplomacy—accusations it firmly denies—as it has deepened its regional trade ties, stoking fears that Beijing could be creating a new paradigm of economic dependence.

For examples, in Djibouti, China has established a military presence, while in Sri Lanka it has taken ownership of critical infrastructure it financed. Amid rumours that Beijing is looking at establish military bases two thousand kilometers off of Australia’s east coast, analysts are drawing parallels with the moves in the Horn of Africa and Southeast Asia.

One could be forgiven for thinking that China is taking over the region, as this narrative repeatedly appears in Australian and regional media. However, while China’s presence has arguably been disruptive, the narrative disregards the autonomy Pacific Island leaders have over domestic affairs, overstates China’s place in the region, and understates the importance of traditional partners such as Australia and New Zealand.

The Pacific Aid Map reveals that China accounted for just 8 percent of total aid between 2011 and 2016. Over the same period, Australia, which was the largest donor in the region, provided 45 percent of all aid.

With strong geographical and historical links to the region, Australia and New Zealand remain the primary partners for the Pacific Islands. Australian aid to the region has remained a constant. The country has invested more than $6 billion, or roughly 3 percent of regional gross domestic product, in close to five thousand individual projects between 2011 and 2016. Rather than focus on one sector, such as infrastructure, Australia has worked across the board, from health to education to civil society.

However, Australia’s aid program is not without flaws. By working in every sector and in every country in the region, its presence is less keenly felt than that of China, which has focused on a few major infrastructure projects. Australia has overcompensated by consistently reminding the region of its contributions, falling into the trap of behaving like a benevolent big brother. In addition, while aid to the region makes up a third of Australia’s overall aid, a series of damaging cuts to its aid program, combined with a disruptive restructuring of governance by merging the Australian Agency for International Development with the Department of Foreign Aid and Trade, has blunted the strategic coherence and effectiveness of Australian aid. Additionally, Australia can be slow to implement its aid and is often not responsive to the requests of its Pacific Island partners. Therefore, China—with little historical baggage and few apparent strings attached to aid offers—can be an appealing new partner.

Besides Australia, China, and New Zealand, there are many other actors operating within the region. France, the United Kingdom, and the United States have expressed interest in increasing their commitments; Japan is the fifth-largest donor and provides 6 percent of all aid to the region. Taiwan also competes for support in the region, which hosts almost a third of the seventeen countries that officially recognize Taiwan. Multilateral agencies, in particular the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, contribute roughly 8 percent of all aid to the region; both have pledged to double their investments in the region by 2020. Despite the enhanced interest around the globe, it will take a great deal of commitment from these partners to change the status quo.

Still, countries aside from Australia and New Zealand, as well as international organizations, should be active in the region. For their part, Australia and New Zealand should still court Pacific Island nations. The region faces critical human development challenges, and there is room for everyone to help. Many of these donors could bring new ideas and relationships—not to mention less baggage. However, a pivot by some of these partners toward the Pacific isn’t likely to drastically shift the dial on the new and competitive status quo.

Policy Implications

An indirect benefit of China’s activity in the Pacific Island region has been a renewed sense of urgency in Australia and New Zealand to step up their engagement. While both countries continue to enjoy their status as the region’s partners of choice, for most of the last seventy years, they have maintained that position largely by default. Leaders of Pacific Island countries often accuse Australia and New Zealand of operating with a degree of benign neglect, only involving themselves at high levels when crises occur. With more options for partnerships, this approach is no longer sustainable. Australia is stepping up, while New Zealand is shifting the dial. Yet, both countries need to think about how to best use the money they are spending.

While Australia is ramping up its diplomacy with regional leaders, often with pomp and ceremony, it should also listen to its peers and treat them with the relevant equivalence deserved. Pacific Island institutions are relatively weak, and bilateral and multilateral relationships are critical to the region’s development. They must be nurtured and built over time. Australia should work with the region’s leaders on the challenges they want to tackle—critical development challenges, migration, climate change, and cultural preservation, among others—rather than ones that only matter to Australians. Simply bringing these leaders to Canberra to lecture them on Chinese lending will not cut it.

Australia should retool its aid program in the region to focus on building up broader relationships between Australian and Pacific Island institutions. Rather than rely on the private sector and multilateral agencies to implement Australia’s aid, it should rebuild this capacity in-house to fully leverage significant aid investments in the region.

In addition, Australia should ease migration requirements for Pacific Islanders, specifically for seasonal workers, but also for those looking to visit more broadly. Almost nine thousand Pacific Islanders enter Australia every year for seasonal agricultural employment; this could rise to as high as one hundred thousand. Distributing these seasonal workers across the region could be profoundly more beneficial than sending foreign aid; it could also help Australian employers. Australia should also consider a special permanent access category visa for Pacific Islanders, allowing a small number of randomly selected people to migrate permanently to Australia. This would take pressure off Pacific Island governments trying to manage exploding populations and build stronger people-to-people links; currently, less than 1 percent of Australia’s population identify as Pacific Islander.

Most critically, Australia needs to act like it is a part of the Pacific Island region and not just as its caretaker. Australia has established a promising road map in its 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. The challenge now is to implement it.

Last month, alongside the Pacific Islands Forum Foreign Ministers meeting, the Lowy Institute launched its new flagship product for the Pacific Island region, the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map. Over the past eighteen months, the team working on the map collected data on close to thirteen thousand projects from sixty-two donors in fourteen countries from 2011 onward. This raw data has been made freely available on an interactive platform, allowing users to investigate and manipulate the data.