Syrian women have fought to secure a significant role in efforts to resolve the conflict. Though several initial rounds of talks included no women in formal roles, up to 15 percent of the negotiators in UN-mediated discussions in December 2017 were women. In January 2018, Russia convened the Syrian National Dialogue Congress in Sochi, but women only constituted 15 percent of party delegates. However, a breakthrough occurred in September 2019, when the Syrian Constitutional Committee was appointed with nearly 30 percent women, the highest percentage ever for a Middle East peace process. The constitutional committee, which is tasked with drafting a new constitution for Syria, is comprised of both a small body and a large body. The small body has continued to meet since 2019 and is comprised of thirteen women out of a total of forty-five members. In addition, the Syrian Women’s Advisory Board—comprised of fifteen members—continues to consult with the UN special envoy for Syria and successfully works across political lines to advocate for the inclusion of women in peace processes and to find consensus on controversial issues critical to stability, including aid delivery and the release of detainees.

Women are at the forefront of conflict resolution and mediation at the local level, leading efforts to negotiate ceasefires, organize nonviolent protests, police the streets, work in field hospitals and schools, distribute food and medicine, and document human rights violations. Women in civil society have adapted to new dangers and stepped into roles traditionally held by men to work on behalf of peace and security, including advocating for the release of political prisoners.

The Syrian conflict began in 2011, when protests against President Bashar al-Assad quickly turned into a war between the government and rebel groups. Over 350,000 people have been killed as of June 2022, according to UN estimates. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights puts the figure much higher, with more than 507,000 deaths. The UN estimates that there are 6.2 million refugees living outside the country, and that an estimated 7.2 million people are displaced within the country. Multiple rounds of peace talks held since 2012, including in Geneva; Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana), Kazakhstan; and Sochi, Russia, led to ceasefire agreements but failed to bring a negotiated end to the crisis. A tenuous ceasefire largely held in the absence of a negotiated agreement, but in November 2024, rebel groups—led by Hayat Tarir al-Sham (HTS)—began making advances. As they advanced on the capital of Damascus, President Assad fled the country to Russia, where he was granted asylum. On December 8, the rebels declared victory and the Syrian Army dispersed. Ahmed al-Sharaa, the leader of HTS, subsequently assumed de facto control of the country and appointed Mohammad al-Bashir, an electrical engineer and rebel leader, as interim prime minister. On March 13, Sharaa, who is now serving as the country’s transitional president, announced that he had signed an interim constitution placing the country under Islamic law for a five-year period. Supporters of the interim constitution point to the fact that it includes a provision guaranteeing “freedom of opinion, expression, information, publication, and press” and also that it guarantees women’s rights to education and work, as well as full “social, economic, and political rights.” But critics are concerned that it puts too much power in the hands of President Sharaa and fails to protect all Syrians, especially minority groups. The draft constitution specifically places the country under Islamic law, which drew immediate concern from the country’s Christian minority.

Ongoing violence is also threatening the country’s stability. Since the fall of Assad, violent clashes have occurred between the new government and forces loyal to the former president, resulting in thousands of deaths. It has also continued between U.S.-backed Kurdish forces—known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—and Turkish militias backed by Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan. Approximately one third of Syria is currently held by a multiethnic coalition of Kurds, Arabs, and other minority groups in an area known as the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). AANES has a progressive government, where women share full and equal rights. Turkey is fiercely opposed to the continued existence of this autonomous Kurdish-led region, and its militias began carrying out intensified attacks in this area when the HTS began making advances in late 2024. In early March 2025, SDF leaders called for a ceasefire with Turkish forces and signed an agreement with the new Syrian government. The agreement promises that the SDF will integrate “all civil and military institutions” into the new Syrian state by the end of 2025. On May 30, a high-level delegation from the SDF traveled to Damascus to work on further implementation of the agreement.

Syrian women have been underrepresented through efforts to resolve the crisis in Syria, though they have played an important role. Although UN-led talks began in 2012, it was not until 2016 that Staffan de Mistura, the UN special envoy for Syria, established a fifteen-member Syrian Women’s Advisory Board to participate as third-party observers in the Geneva peace talks. The advisory board, which is the only such body established by a UN special envoy, drew on Syrian women’s experience and expertise to provide recommendations on issues of outreach and engagement, and advocated for a permanent end to the crisis even in the absence of formal peace negotiations. Notably, the parallel Russian-led talks mostly blocked women’s participation .

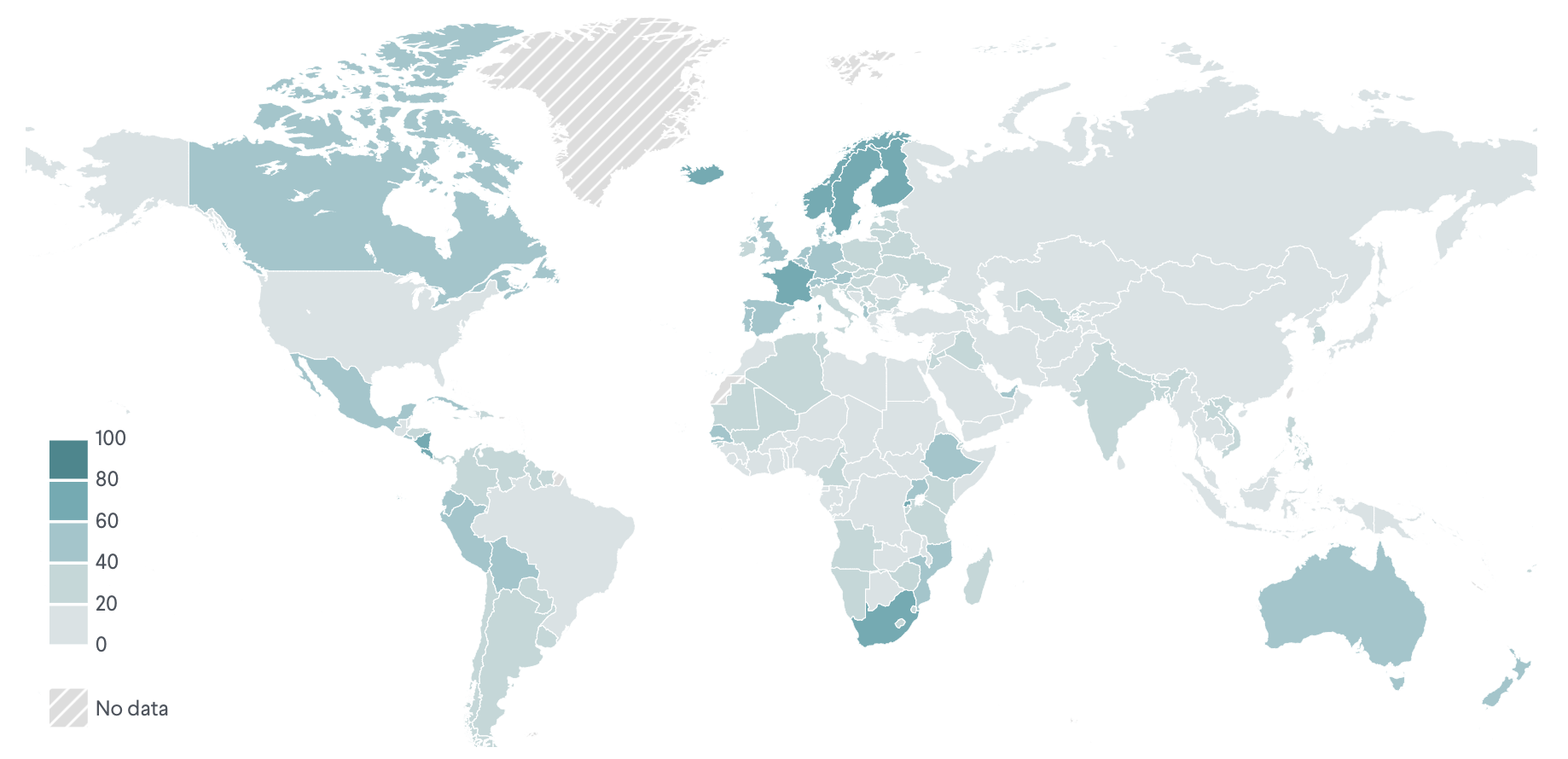

Women were also outnumbered in official roles in UN-led negotiations, composing only 15 percent of the opposition and government delegations at the December 2017 talks in Geneva. However, the Syrian Women’s Political Movement set a goal for a 30 percent quota for women’s participation to ensure an inclusive conflict-resolution process that delivers justice for all Syrian war victims. This goal was largely reached in 2019, when the UN established the Syrian Constitutional Committee with nearly 30 percent women. The constitutional committee, which included members from the Syrian government, the opposition, and civil society, was tasked with drafting a new constitution for Syria. It was composed of both a small body and a large body. The small body, which included thirteen women out of a total of forty-five members (29 percent), met eight times between October 2019 and June 2022. The large body, composed of 24 women out of 150 members (16 percent), held its first and only meeting in October 2019.

The interim Syrian government headed by President Sharaa has not yet announced a formal negotiating structure for efforts to establish a unified Syria. However, the government did establish a Women’s Affairs Office, headed by Aisha al-Dibs and named Maysaa Sabreem as the head of Syria’s central bank—the first woman ever to hold the position. As well appointing Mohsena al-Maithawi as governor of Suwayda, Dibs has spoken publicly about a commitment to ensuring that women from all provinces and ethnicities will be involved in Syrian peace and governance efforts. While there is concern about HTS’s past record on women, Dibs said “it is known to us all that the Syrian woman, historically, is a highly effective woman, able to lead across all fields. Today, we are in the process of bringing her back to this leading role in building Syria, a new country, the free country we all aspire for.” Furthermore, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—whose support is critical to any agreement—are currently cochaired by a woman, Layla Qaraman. Still, many women’s rights groups are concerned with how the Islamist law will be interpreted by Dibs, who has critiqued human rights organizations who worked to empower Syrian women but failed to respect “their duties and responsibilities.” There is also concern about the appointment of Shadi al-Waisi as justice minister, who, as a judge, sentenced two women to death over charges of adultery and prostitution.

In late February 2025, the interim Syrian government held the National Syrian Dialogue Conference in Damascus, which was billed as an effort to help build an inclusive government. In advance of the event, the government appointed a preparatory committee that included seven people, two of whom were women. Dozens of women participated in the two-day conference, and thousands more were able to contribute opinions online. The conference ultimately concluded in a statement supporting the role of “women in all fields.” But critics, including the Syrian Women’s Political Movement, charge that the conference failed to explicitly support women’s rights. And certain minority groups were excluded, including the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, who were not invited . There is also no clear indication about how or if the recommendations reached at the conference will be incorporated into Syrian laws moving forward, or whether the dialogue process will continue.

- Women

- Men

women

women

Although women have been underrepresented in formal peace processes in Syria, women have made valuable contributions to securing peace in local communities across the country. In October 2024, UN Special Envoy Geir O. Pedersen briefed the Security Council [PDF] that “Syrian women continue to identify opportunities for the political process to move forward, build trust, and give voice to the voiceless. And everywhere, Syrian women are on the frontlines, bearing the burden of this conflict for their communities and families.” Since the fall of Assad, women, many of whom are planning to return to Syria after having fled, have spoken out about their desire to build an inclusive Syria. And many women are currently pushing to ensure that women compose at least 30 percent of all decision-making bodies going forward.

Broaden the agenda. Women at the negotiating table and in civil society have raised a number of issues critical to long-term peace and recovery, including delivery of aid and food, the release of detainees , inquiries into disappearances, and the effects of economic sanctions. Syrian women have also pushed for anti-gender-based violence measures—as well as other issues involving women—to be included in any new Syrian constitution.

Work across lines. With members drawn from across the political spectrum, the Syrian Women’s Advisory Board has set an example for finding consensus on controversial issues that stalled formal talks, including aid delivery and the release of detainees. Women also established Damascus-based Mobaderoon, a civil society group aimed at relieving tension and localized violence in communities from the arrival of internally displaced Syrians. Additionally, digital spaces like the Civil Society Support Room allow women facilitators to create a digital space for engaging in these peace processes.

Negotiate local cease-fires. Syrian women successfully negotiated the cessation of hostilities between armed actors in several areas to allow for the passage of aid. In the Damascus suburb of Zabadani, for example, a group of local women pressured a militia to accept a twenty-day ceasefire with regime forces. In Banias , the government heeded the demands of two thousand women and children who blocked a highway, resulting in the release of hundreds of men from neighboring villages who had been illegally rounded up.

Do the work local governments should do. Women in civil society groups have also worked in field hospitals and schools , distributed food and medicine, and organized nonviolent protests. In one opposition-held city, women have formed all-female police brigade , which has access to areas their male counterparts do not and provides families with critical services. In many instances, following negotiations, women continue to work with political actors to obtain access to essential services and resources for their survival.

Document human rights violations. A number of women and women’s groups report on kidnappings, detentions, disappearances, and other human rights violations by armed actors in Syria. Women have actively negotiated with armed groups to combat child recruitment and to secure the release of political prisoners. These activists include the founders of the Violation Documentation Center , which was one of the first organizations to report attacks involving chemical weapons. These groups provide critical data and analysis to international watchdogs and parties to negotiations.

“As women we are responsible for making that connection between the ground and what’s happening at the table. . . . [We translate] the messages that are coming from women on the ground, from civil society, to a political message to create policies that actually benefit all.”

— Mariam Jalabi, founding member of the Syrian Women’s Political Movement and representative of the Syrian Opposition Coalition to the United Nations