A Tug of War Between East and West

Ukraine tacked toward Russia ahead of the EU summit but the geopolitical contest for all three sides will likely intensify, says expert Jan Techau.

November 26, 2013 10:54 am (EST)

- Interview

- To help readers better understand the nuances of foreign policy, CFR staff writers and Consulting Editor Bernard Gwertzman conduct in-depth interviews with a wide range of international experts, as well as newsmakers.

The European Union’s eastern ambitions derailed last Thursday when Ukraine suspended work on an association agreement that was to serve as the centerpiece of this week’s highly anticipated Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius. For Carnegie Europe director Jan Techau, the decision can best be understood as an existential tug of war taking place between the EU and Russia over former Soviet bloc nations. "Russia upgraded [the Eastern Partnership] to a geopolitical contest," he says, referring to the crippling economic sanctions it threatened to impose on Kiev should it sign the EU deal. But Techau says the EU model of governance has enduring value for Ukrainians and the region.

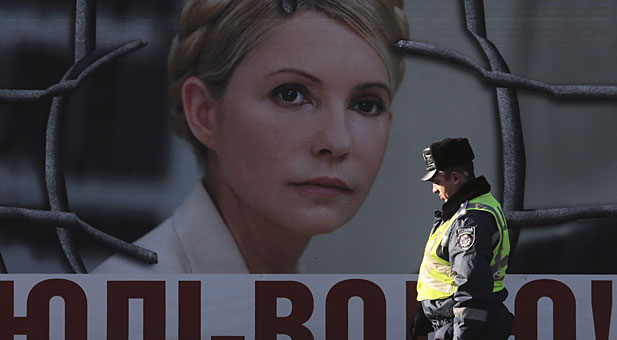

An Interior Ministry officer walks past a board displaying a portrait of jailed former Ukrainian prime minister and opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko in central Kiev. (Photo: Konstantin Chernichkin/Courtesy Reuters)

An Interior Ministry officer walks past a board displaying a portrait of jailed former Ukrainian prime minister and opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko in central Kiev. (Photo: Konstantin Chernichkin/Courtesy Reuters)Is it too soon to write off Ukraine’s bid for European alignment? How significant is it if Ukraine fails to sign the Eastern Partnership Agreement this week?

It’s very significant but I don’t think it’s the end of the story. There are two things behind the Ukraine’s recent decision not to sign the agreement. The Ukrainian elites have successfully implemented a kind of an equidistant strategy between Russia and Europe for the last few years. The oligarchs who are behind this regime and want to keep it in power live by a very simple calculation: If they get too close to Europe and adopt European standards of transparency and the rule of law, their business model suffers—at least in the mid- to long-term. And if they get too close to Russia, they will be minions of Moscow. They can’t get too close to either side so they’ve been trying to play one against the other and trying to implement a course of equidistance.

More on:

[It’s true that Ukrainians] are a lot closer to the Russians in many ways, including culturally. But you see the demonstrations of the past weekend and it’s very clear you have a deeply split country. I would say for the time being, for the next few months, this is where we are. But in the long term, over the next few years, there’s going to be a lot of movement in the Ukraine, and it’s by no means clear where it will end up.

Was it a mistake for the EU to make this a zero-sum proposition for Ukraine, essentially making it choose between Europe and Russia?

Europeans initially wanted to play the Vilnius summit and the entire association agreement summit as a technical matter: lots of compliance issues and so on and so forth. But Russia upgraded it to a geopolitical contest. Europeans could probably have played it more diplomatically, a bit more elegantly, but in the end it was more the Russian position that turned it into that kind of zero-sum contest.

There were tens of thousands of protestors who turned out across the country this past weekend, and polls show that a majority of Ukrainians remains supportive of European integration. Is President Yanukovych at risk of losing the Ukrainian public with last Thursday’s decision?

I don’t see a real threat to his power as of yet. The real threat to his power can only come from two sources really. Either there’s going to be a widespread kind of revolution, and that’s not in the cards, or the oligarchs, the backbone of the political system, decide that he is not the kind of guy who can guarantee their survival any longer, and that also doesn’t seem to be the case. For the moment, he’s safe.

Former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko has made appeals to delink the signing of the agreement with her release. Do you think it was a mistake for the EU to make her release a condition of signing the association agreement?

More on:

"The EU and especially Germany took this case very seriously and really insisted that the Tymoshenko case be linked to the association agreement. I think they overplayed their hand."

That’s a clear "yes." I would not have played it this dramatically. The EU and especially Germany took this case very seriously and really insisted that the Tymoshenko case be linked to the association agreement. They overplayed their hand. That’s probably the only real mistake that they made in this. Again, I don’t think that’s the key problem with [Ukraine not signing]; the underlying power considerations that I mentioned earlier are the real reason for why this didn’t come to pass. But it was certainly something that gave the Ukrainians a wonderful excuse for not [going forward with the agreement].

Since its creation in 2009, the Eastern Partnership has, at times, taken a backseat while European policymakers struggled to contain the economic crisis. Do you think that’s weakened the partnership program?

There was no lack of attention, political will, or unity among Europeans in the run-up to the Vilnius summit. They were very united and determined in bringing this to a positive end and they clearly demonstrated a strong interest in the region. So, could they have spent a little more money? Perhaps. Could they have maybe engaged more a little bit earlier? Almost certainly.

What’s interesting was Germany’s role in unifying the EU. Germany was always very cautious about the Eastern partnership because they thought it was too anti-Russian. But Merkel changed her position after the Putin-Medvedev job swap, which was a huge blow for Russian credibility. The second incident was the Pussy Riot case, where people saw how brutally the system could react to a relatively minor incident. So the combination of these things made Germany come around and adopt a much more critical position of Russia and that gave the Eastern partnership the weight it needed.

So is it that Europe’s less attractive to the East in the wake of the crisis?

"There’s less magnetic power emanating from Europe but, at the same time, it’s still the only party in town."

Yes, Europe is less attractive. There’s no doubt that the crisis has hurt Europe quite significantly, both economically as a beacon of success and as the market you want to join, and also politically for the kind of disunity you can see. But it hasn’t destroyed the European model. It has damaged the model. It is now less attractive and there’s less magnetic power emanating from Europe but, at the same time, it’s still the only party in town. If you want to make a choice between Russia and the EU, just look at any of the indicators. And, despite this weakened model, the EU is still the best that’s out there for anybody in the region.

What do you think is at stake for Putin in Ukraine’s decision, and should the EU fear the Russian president’s plans for a Eurasian Union?

There’s a lot of imagined fear in Russia. The Russians know down deep that the one border in their huge country that they needn’t worry about is their western border, which means the Europeans are the best neighbors that they have. The real danger comes from the southern and southeastern borders; threats to Russian sovereignty are not coming from the West. That’s the sober analysis.

In reality, Russia is completely obsessed with the West. It has a huge inferiority complex and it still feels that the West is trying to encircle them and move closer to the Russian heartland. And that’s very deeply engrained in Russian thinking and it’s centuries-old—not a twentieth-century invention.

The Eurasian Union is a Russian domination scheme and is not an exercise in partnership. The last doubts about that were eradicated when we saw how Russia convinced Armenia to join, which was done by brute force, essentially. And so this is a way of reinstating a certain kind of Russian dominance over its immediate neighborhood. It’s not a competitive model that could outshine the EU, so I don’t think that the EU needs to fear that model at all. What the EU needs to fear is the attractiveness—or the lack of attractiveness—of its own model. The proper answer to the Eurasian Union is for the EU to get its own house in order, to become more competitive, to sort the politics of the crisis out, and get the euro stabilized.

Does the EU need to rethink its handling of the Eastern partnership in light of this current setback?

"This is really a geopolitical competition and it’s that way because of the Russians. And this is how the Eastern partnership will be played from now on."

The way the Russians played this over the last half year has fundamentally changed the Eastern partnership. It’s no longer a situation where you can pretend that this is only about technicalities and some kind of soft win-win situation, the way the Europeans always like to play it. This is really a geopolitical competition and it’s that way because of the Russians. And this is how the Eastern partnership will be played from now on.

The Europeans have already changed their approach in the run-up to the Vilnius Summit as they started to respond to Russian hardball with hardball. That’s great. My worry is they’re not going to be able to keep that going. The attraction to open societies—a democratic, liberal model is also very much there. And Ukrainians want to live like this: they don’t want to live in a corrupt countrywhere their children have no future, where the education is poor, where the social data is all wrong. But to stay attractive, the Europeans must get out of their slump and must turn the EU back into a strong symbol of integration that gets you more freedom and wealth. That’s still how it works—but it’s at risk. The Russians look at this as a model in decay, but they’ve got it all wrong. In the long term, it’s the Russian model that will lose lots of its attractiveness.

Online Store

Online Store