Introduction

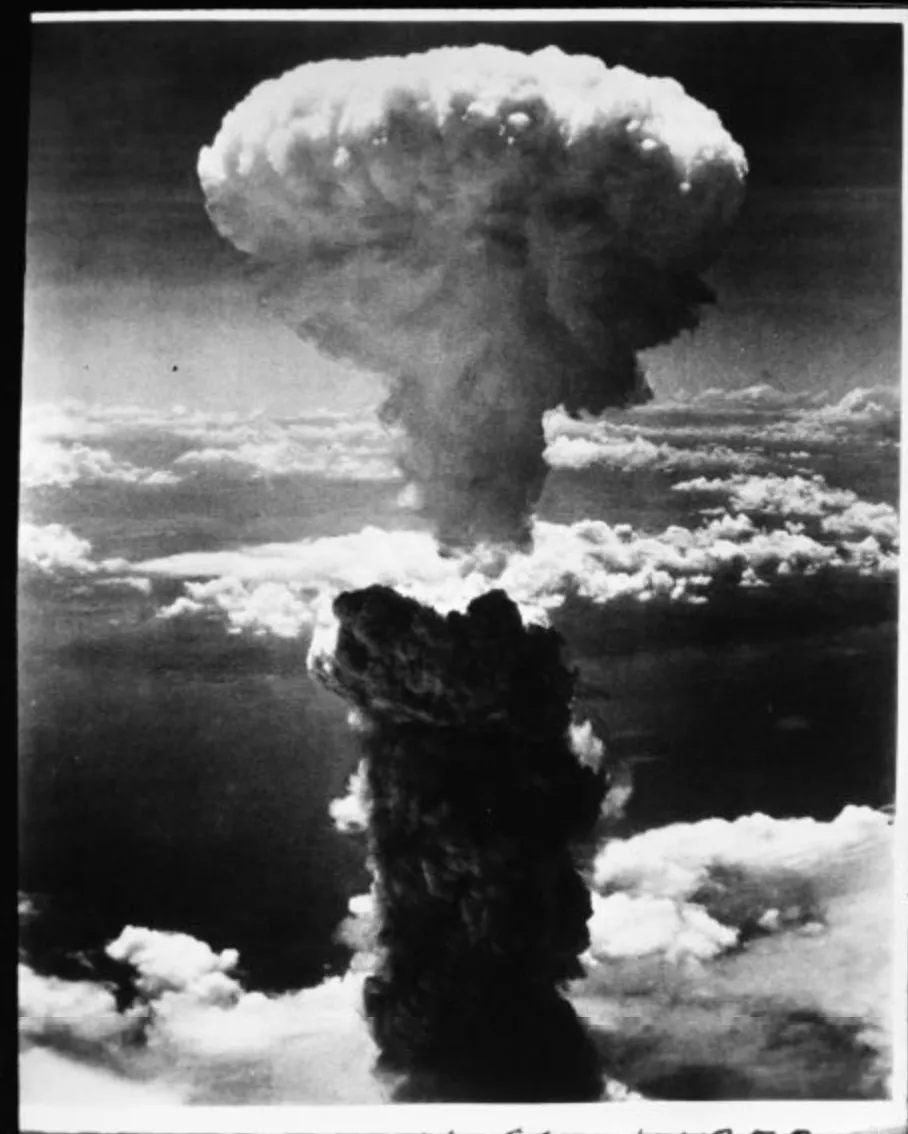

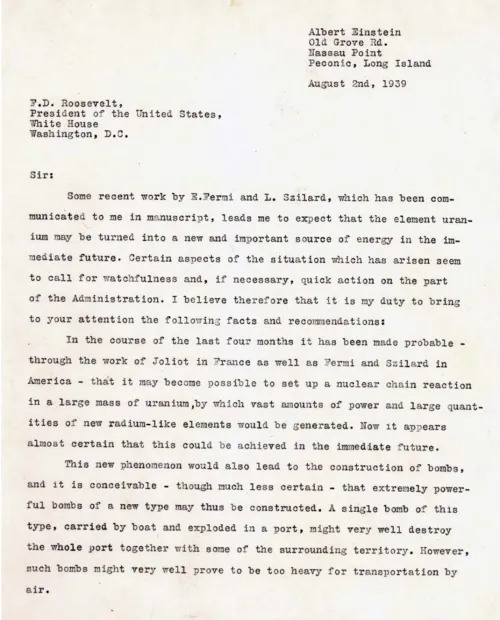

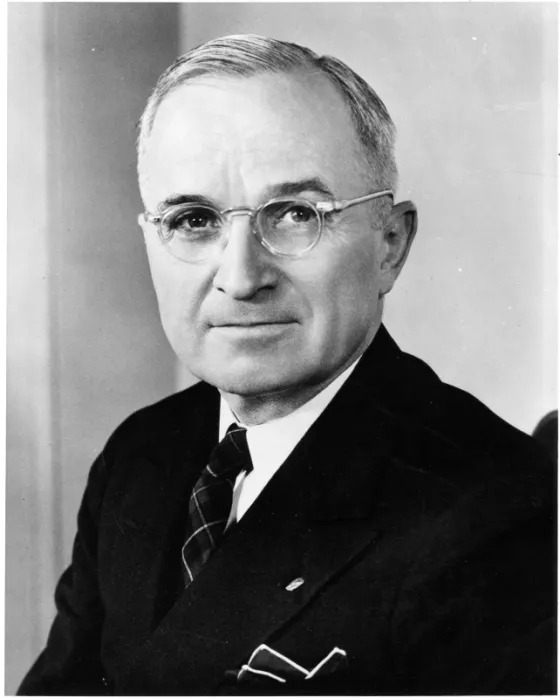

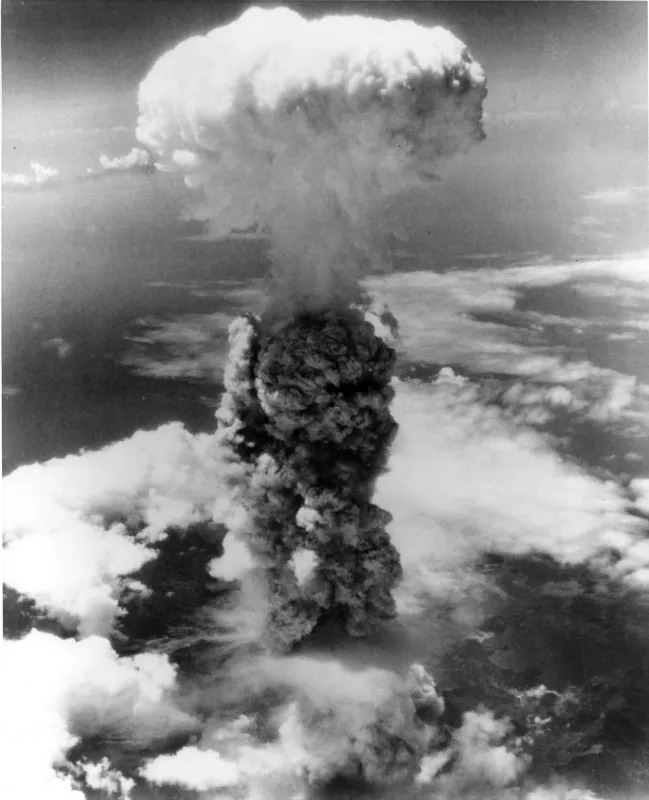

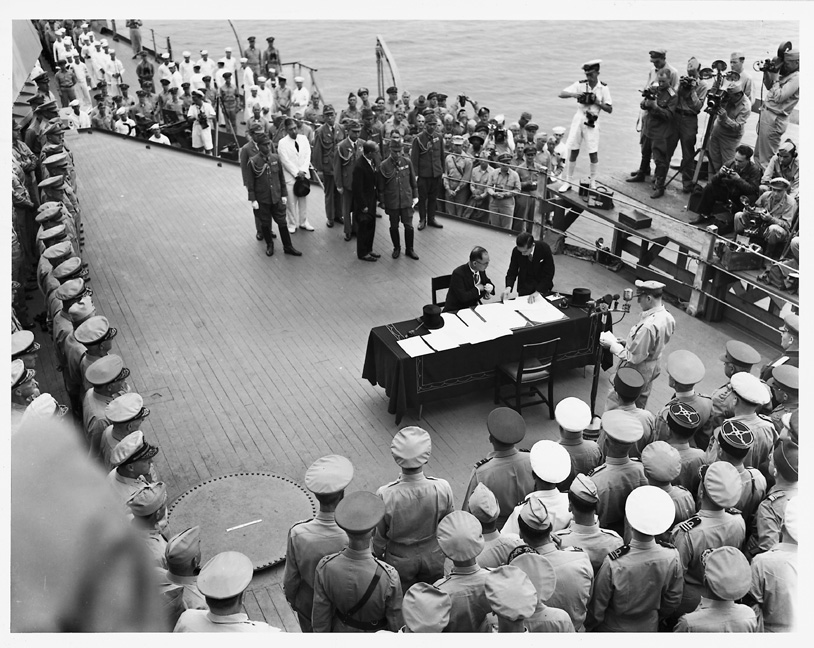

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. That first-ever use of an atomic weapon killed an estimated 140,000 people in all, most of whom were civilians. Three days later, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Some 40,000 people, again mostly civilians, died instantly. Another 34,000 died agonizing deaths in the weeks that followed. President Harry S. Truman argued that the bombings were necessary to compel Japan’s surrender and to avoid what likely would have been a far deadlier U.S. invasion. Truman’s decisions, and particularly the decision to bomb Nagasaki, remain hotly debated. The attacks subjected civilian populations to horrific devastation with long-lasting effects. The bombing of Nagasaki was launched two days earlier than planned to avoid bad weather, leaving the Japanese government less time to assess what had happened to Hiroshima and possibly quit fighting. Truman’s private comments suggest that his decision to bomb Nagasaki went beyond forcing Japan’s surrender to include intimidating the Soviet Union. SHAFR historians ranked the bombing of Nagasaki as the tenth-worst decision in U.S. foreign policy history.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Kimber Quinney

Professor of History, California State University San MarcosJohn Van Sant

Associate Professor of History and Director of History Graduate Programs, University of Alabama at Birmingham