Introduction

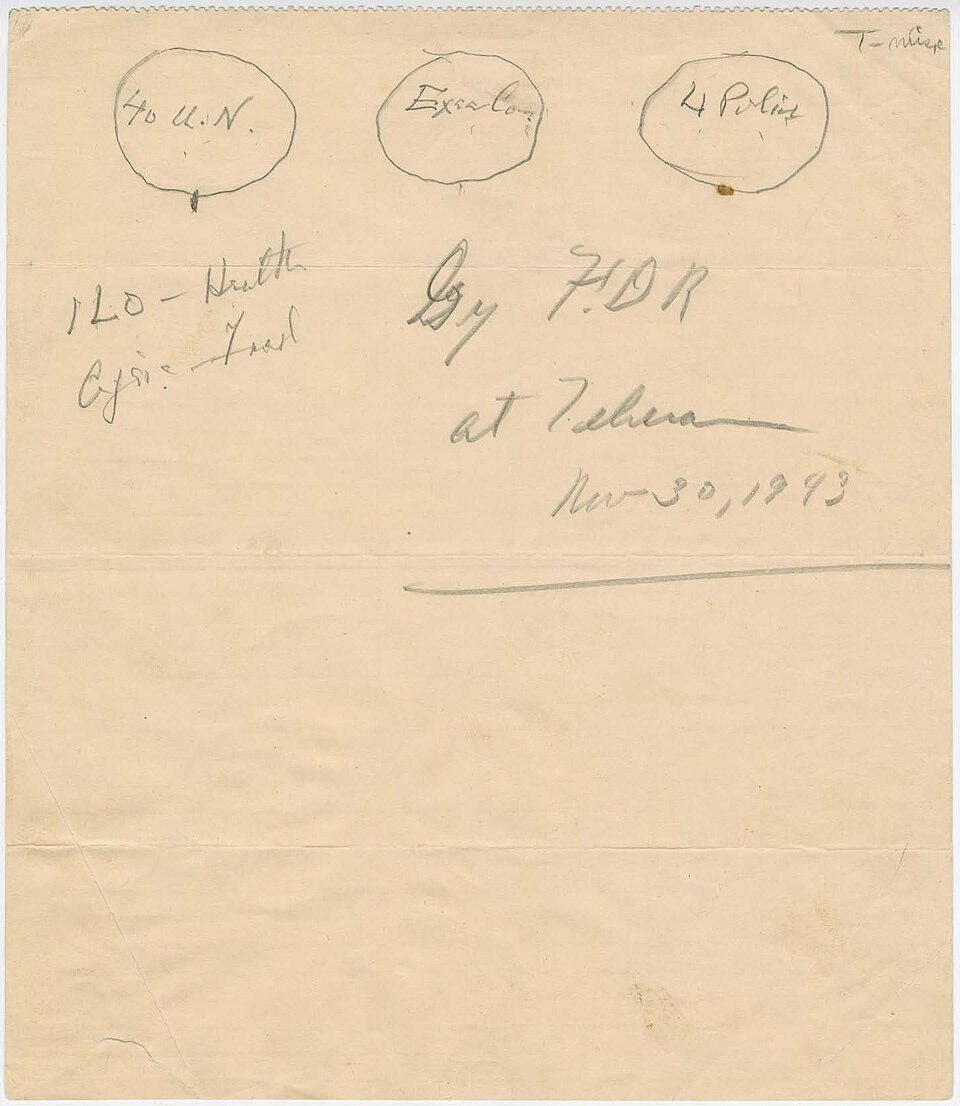

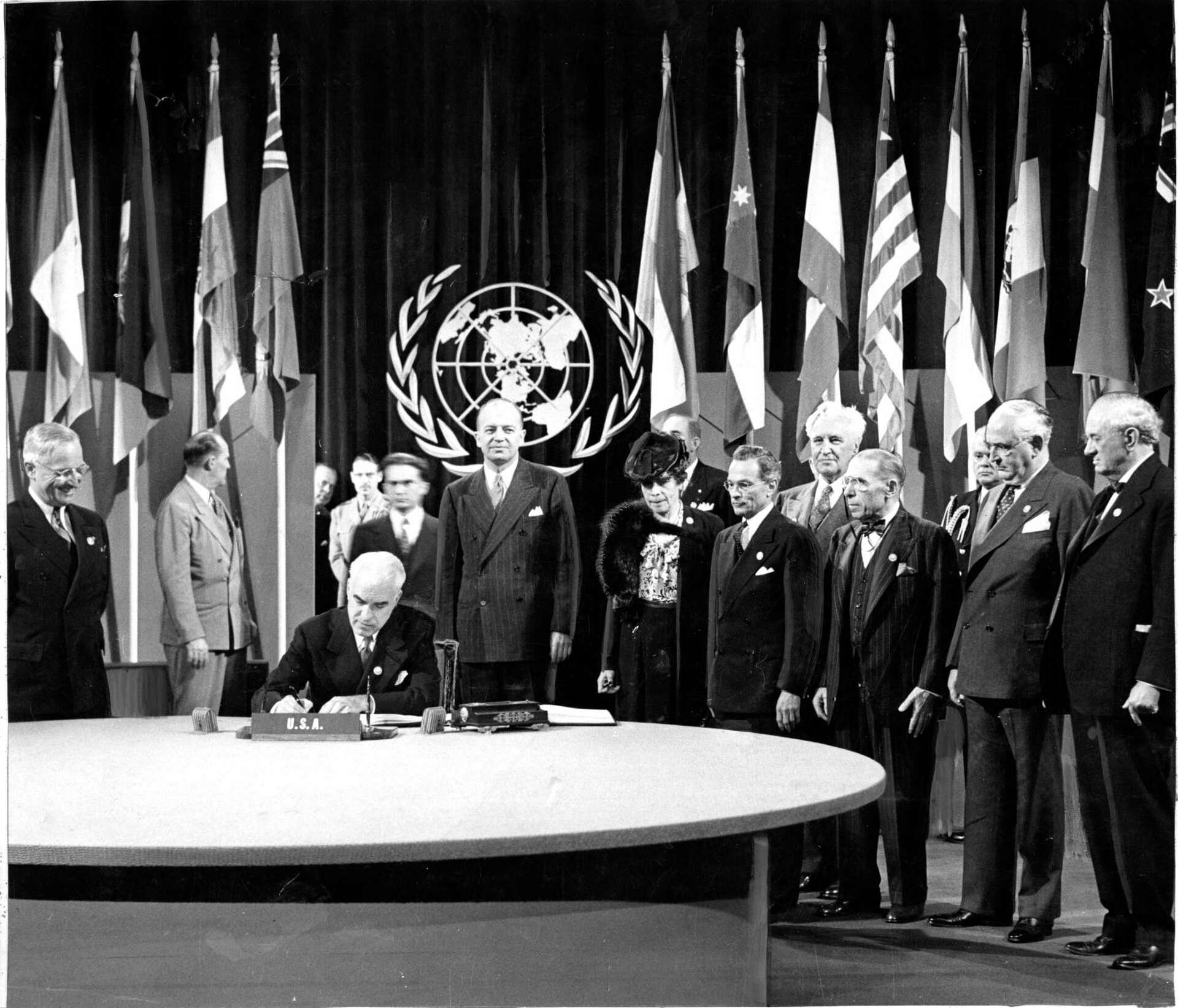

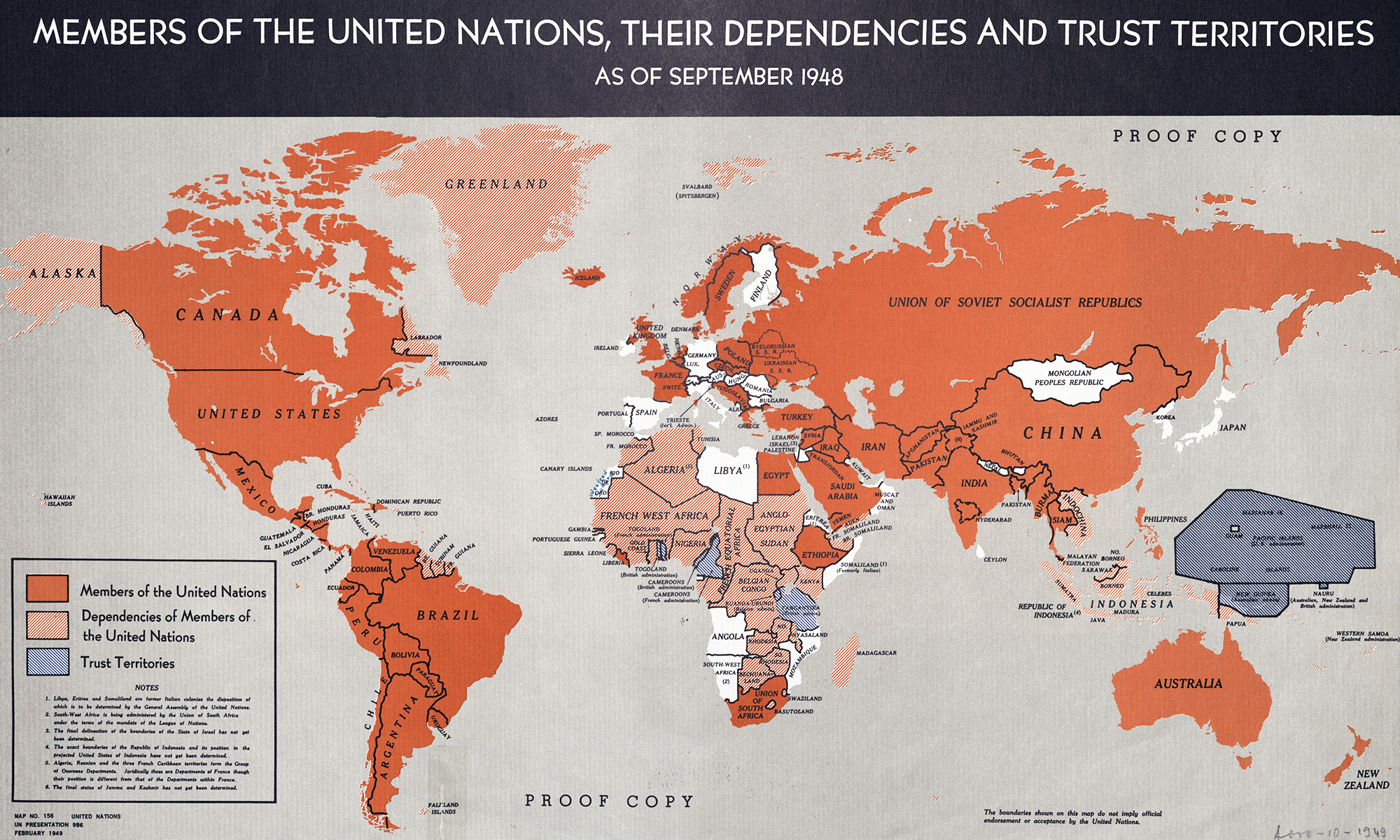

On October 24, 1945, the Charter of the United Nations came into force, establishing the United Nation’s structure, principles, and purpose. The new organization was the culmination of a yearslong effort led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died six months earlier. The objective had been to address the failures of the League of Nations, which was created after World War I, by developing a new international institution that could formalize common efforts to maintain global peace and security, develop friendly international relations, and tackle economic, social, cultural, humanitarian, and public health problems worldwide. Although the United Nations has fallen short of fulfilling Roosevelt’s lofty goals, its role as a forum of international debate, its many peacekeeping operations, and its wide-ranging humanitarian activities nonetheless mark its founding as a major triumph for the United States. SHAFR historians ranked the creation of the United Nations as the second-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Lloyd Gardner

Professor Emeritus of History, Rutgers UniversityJames Stocker

Associate Professor of Global Affairs, Trinity Washington UniversityKevin Grimm

Assistant Professor of History, Regent UniversityAdriane Lentz-Smith

Associate Professor of History, Duke University