Introduction

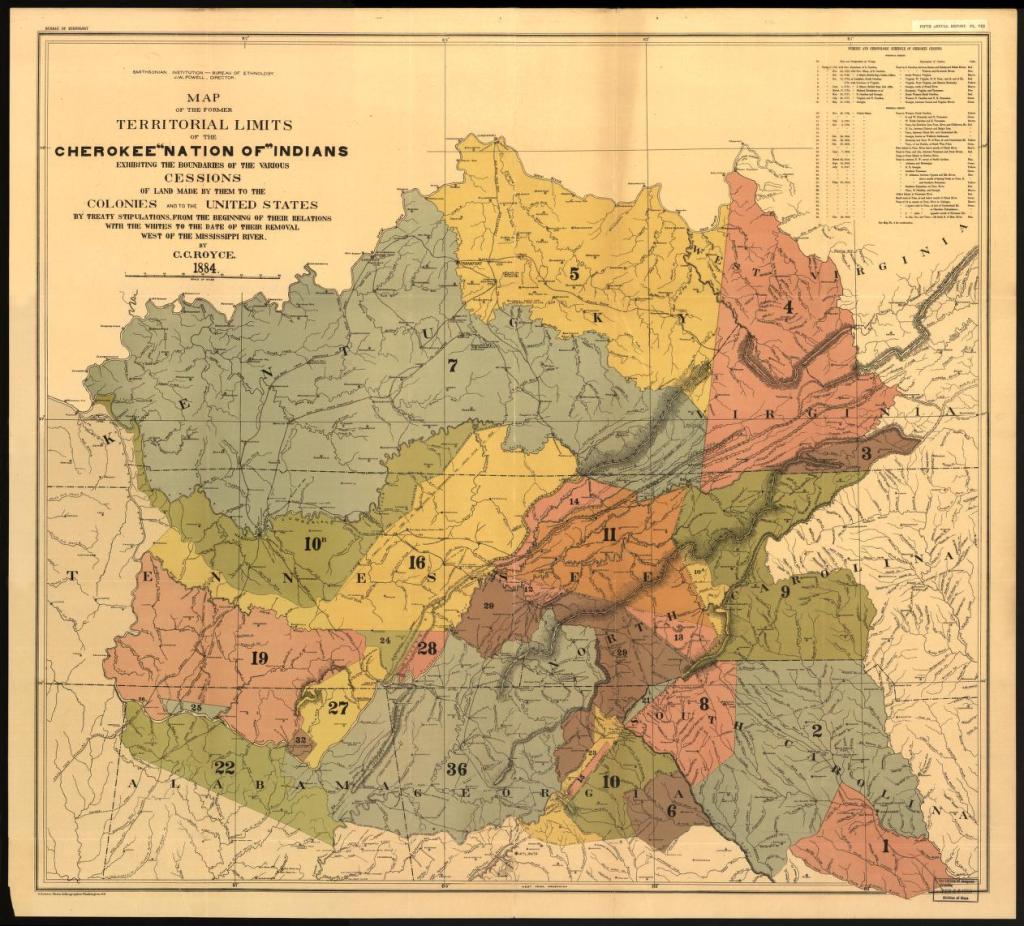

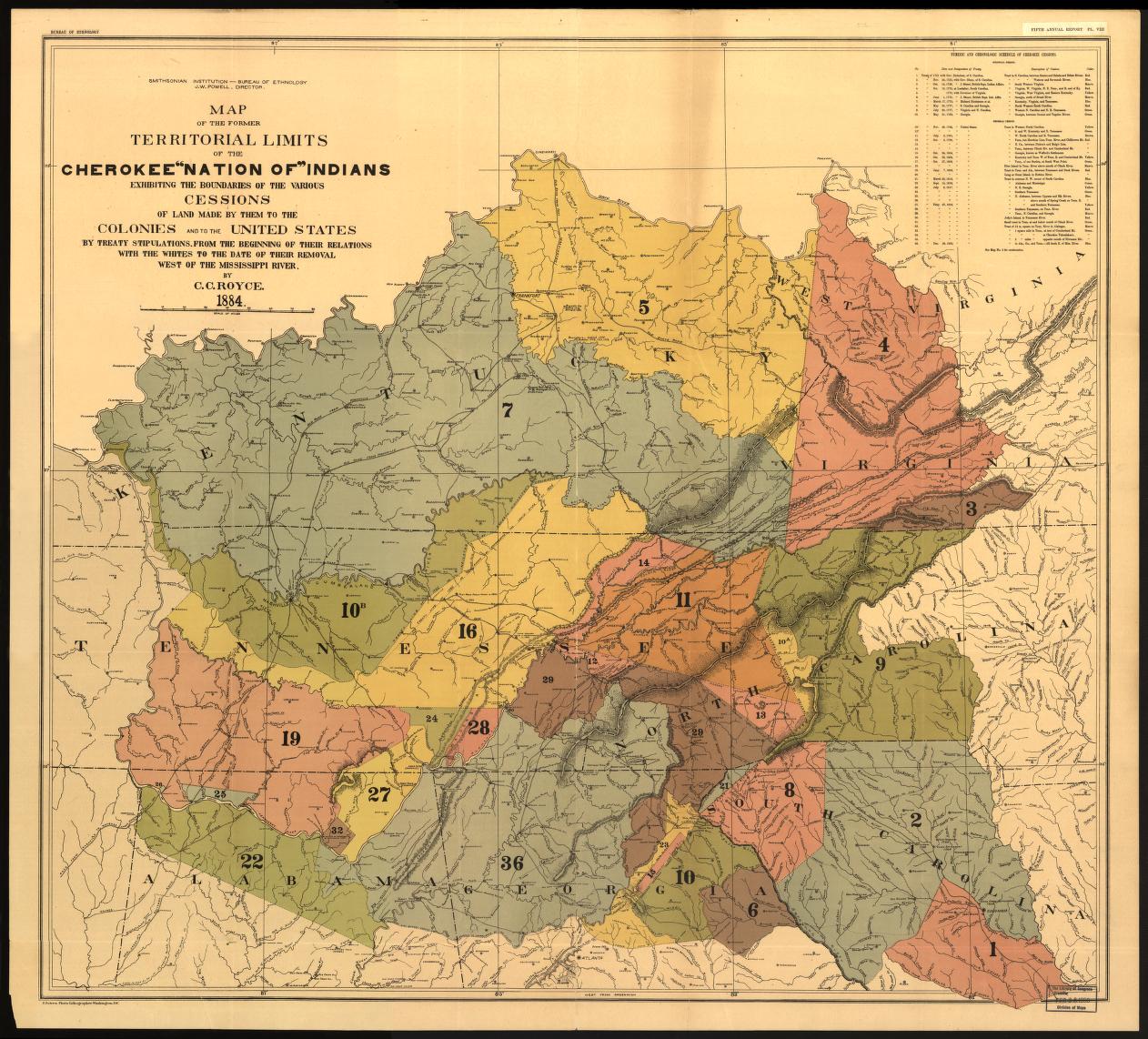

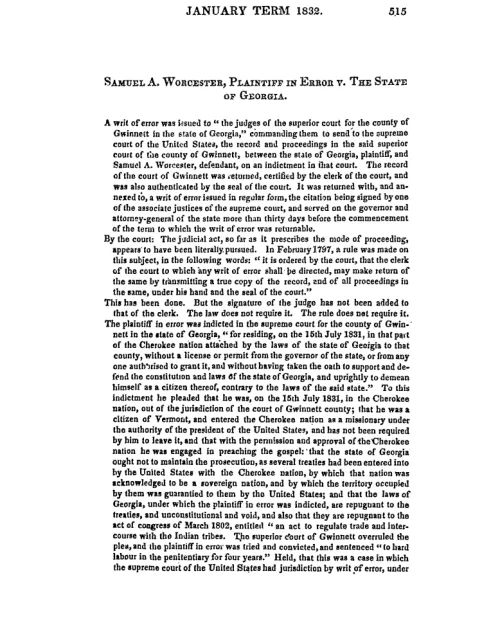

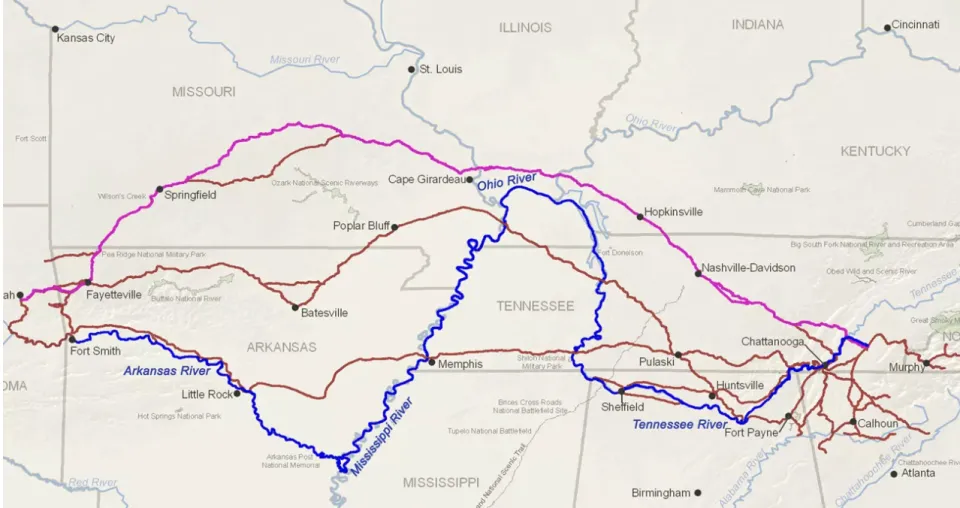

In the early nineteenth century, white settlers in the eastern United States increasingly encroached upon the lands of Native Americans. Although the U.S. government had signed treaties demarcating native territory, political pressure grew to disregard them. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to grant lands west of the Mississippi River to Native American tribes that gave up their lands east of the river. In 1832, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans constituted “separate nations” who were not subject to state law. President Andrew Jackson ignored the ruling. On May 23, 1838, the first members of the Cherokee Nation were pushed out of their lands in what is now the southeastern United States and forced to walk to their new territory in northeastern Oklahoma. Four thousand of the sixteen thousand Cherokee who began the journey died on what became known as the Trail of Tears. SHAFR historians ranked the forcible removal of the Cherokee Nation as the sixth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Anthony Guerrero

Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History, Temple UniversityJessica Chapman

Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Professor of History Chair, Department of History, Williams CollegeEmily Conroy-Krutz

Professor of History, Michigan State University