Introduction

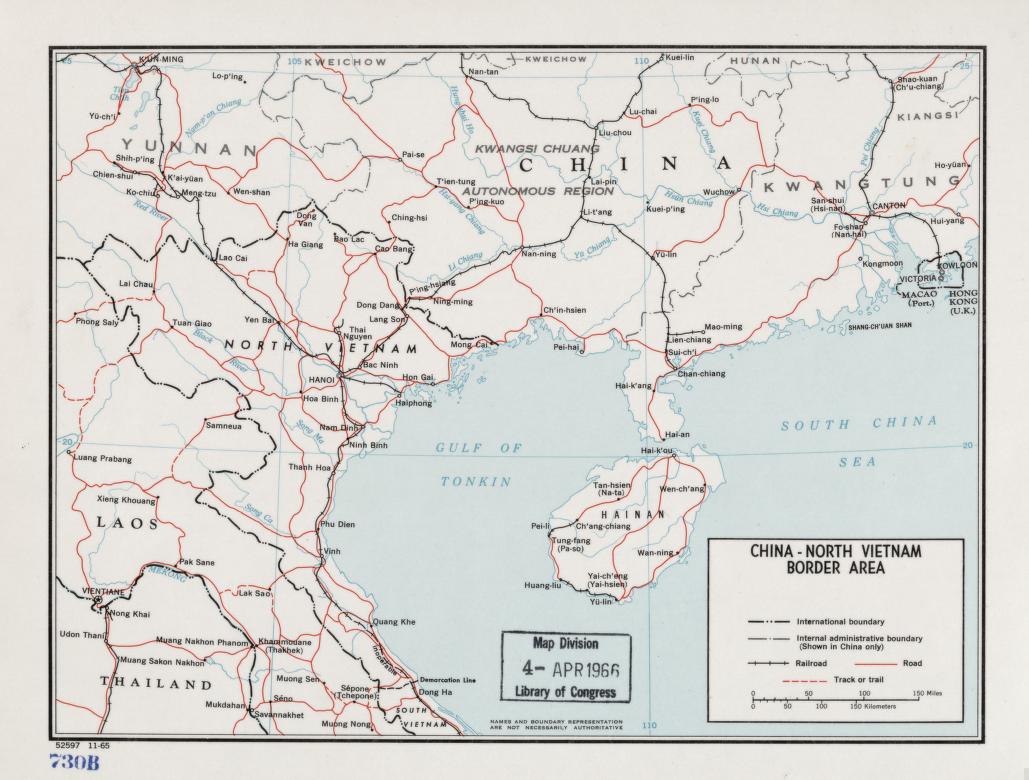

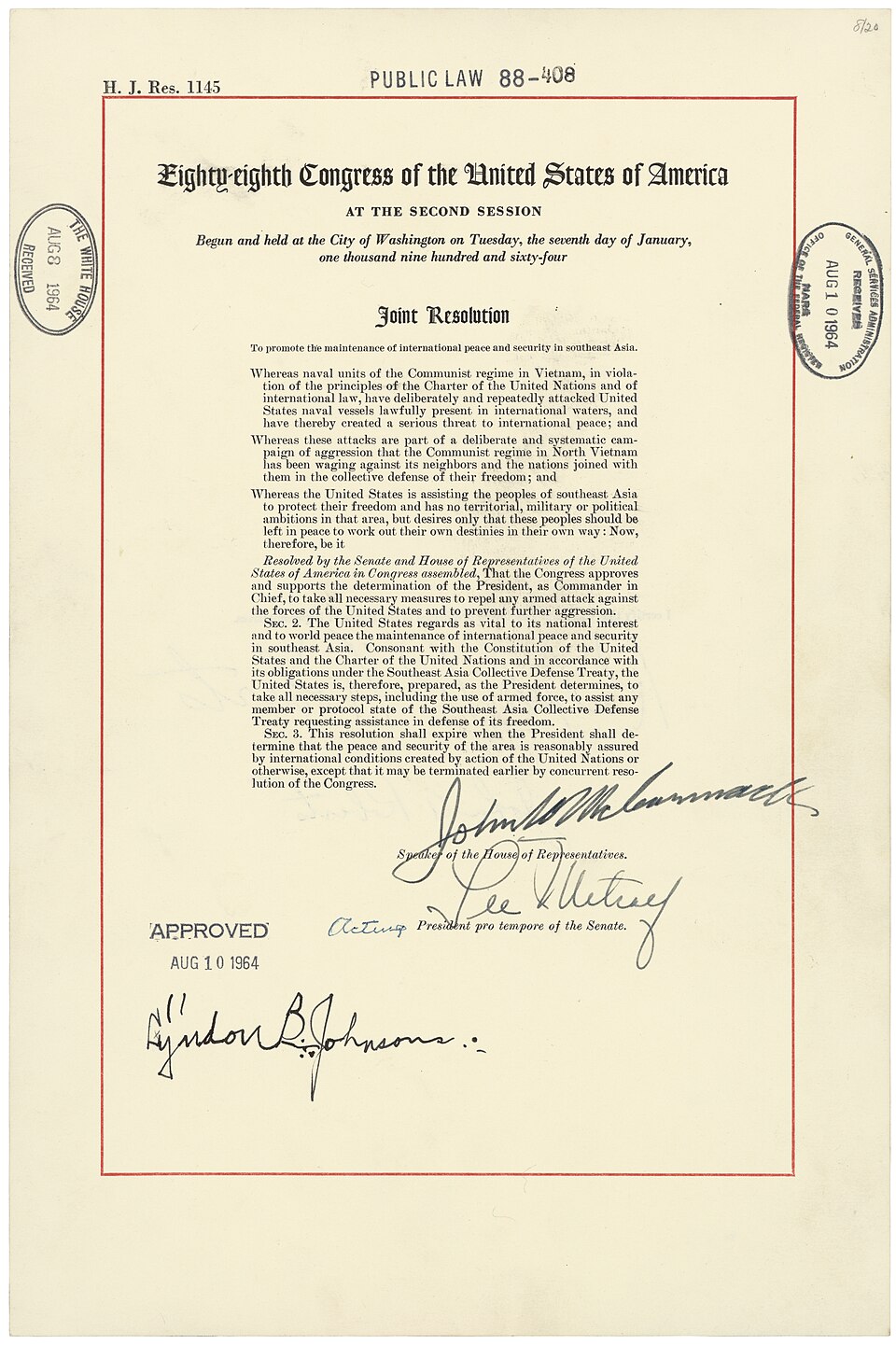

On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese patrol boats attacked the USS Maddox, a destroyer operating in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam. Two nights later, the Maddox reported that it had come under fire again. President Lyndon B. Johnson responded to the news by ordering airstrikes on North Vietnam—the first overt U.S. attack on the country. Johnson also asked Congress to endorse his decision to confront North Vietnamese aggression. Congress complied in less than seventy-two hours by passing the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. What members of Congress did not know was that much of what the Johnson administration told them about why the Maddox was in the Gulf of Tonkin was untrue and that the second attack likely never occurred. Acting in haste and with bad information, Congress approved deepening U.S. involvement in what would become the Vietnam War. SHAFR historians ranked the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution as the ninth-worst U.S. foreign-policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Christopher McKnight Nichols

Wayne Woodrow “Woody” Hayes Chair in National Security Studies and Professor of History, The Ohio State UniversityCharlotte Brooks

Professor of History, Baruch CollegeMatthew Jagel

Adjunct Instructor in History, Saint Xavier CollegeGregory Graves

Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History, George Washington University