Introduction

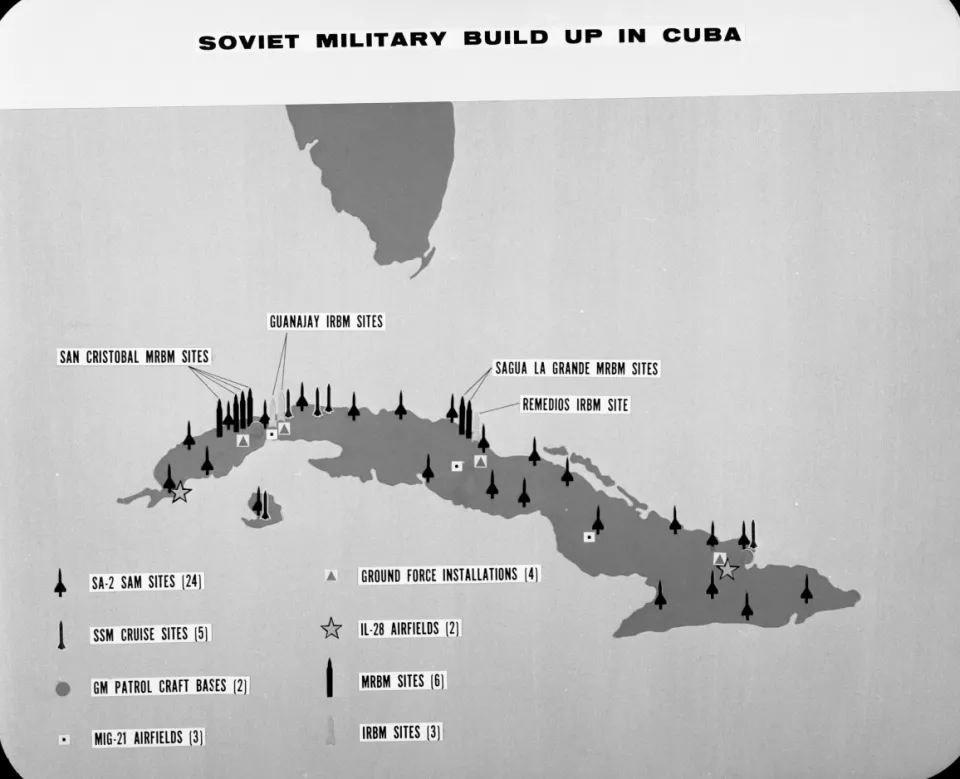

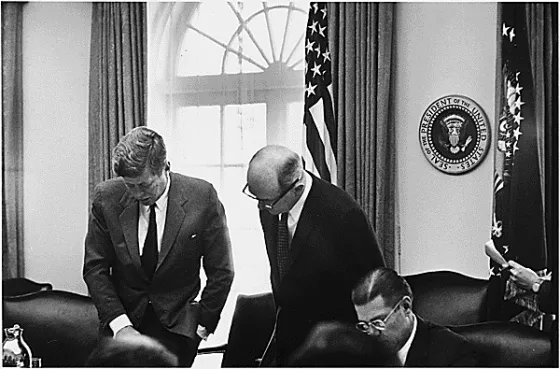

A U.S. Air Force surveillance flight over Cuba in October 1962 turned up evidence of what U.S. officials had feared: the Soviet Union was installing nuclear-armed missiles on the island. The discovery triggered a thirteen-day crisis that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. President John F. Kennedy initially favored air strikes to take out the missile sites before they became operational. As a first step, he ordered a naval quarantine, or blockade, of Cuba. But worried about escalation to the unthinkable, he pursued backchannel communications with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev that ended the crisis. Alarmed by how close they had come to nuclear Armageddon, Kennedy and Khrushchev subsequently negotiated several agreements that lowered tensions between their two capitals and opened the door to the arms-control era. SHAFR historians ranked JFK’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis as the tenth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Matthew Jagel

Adjunct Instructor in History, Saint Xavier CollegeGregory Graves

Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History, George Washington UniversitySimon Graham

Postdoctoral Research Affiliate in History, University of SydneyRenata Keller

Associate Professor of History and Undergraduate Advisor, University of Nevada, Reno