Introduction

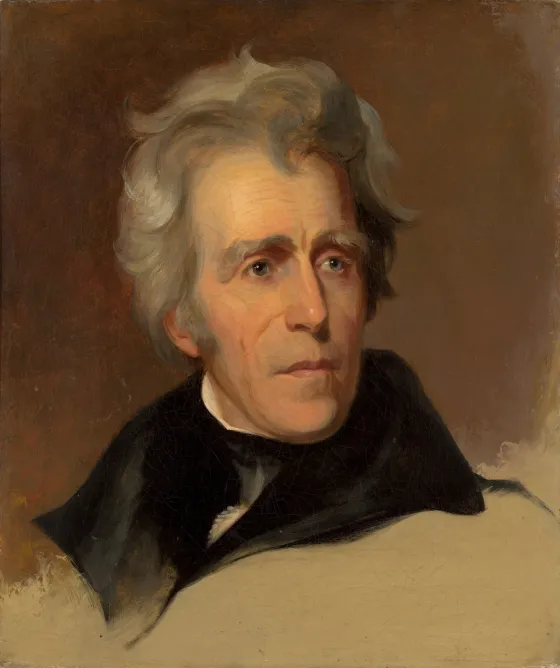

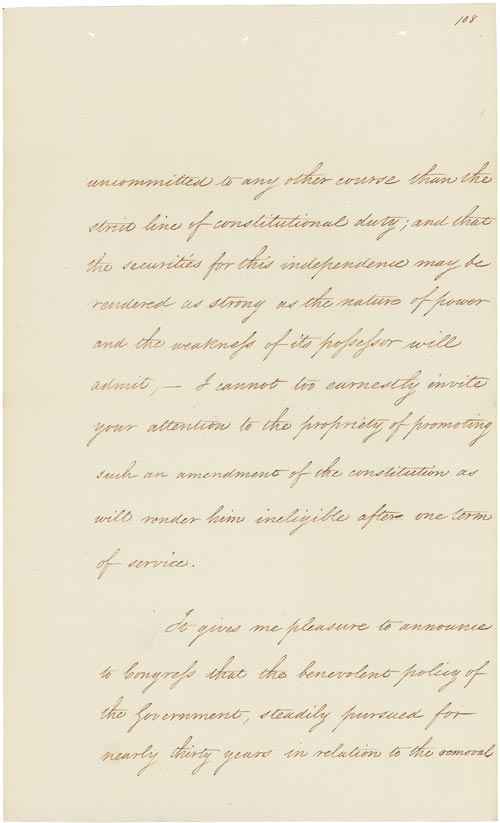

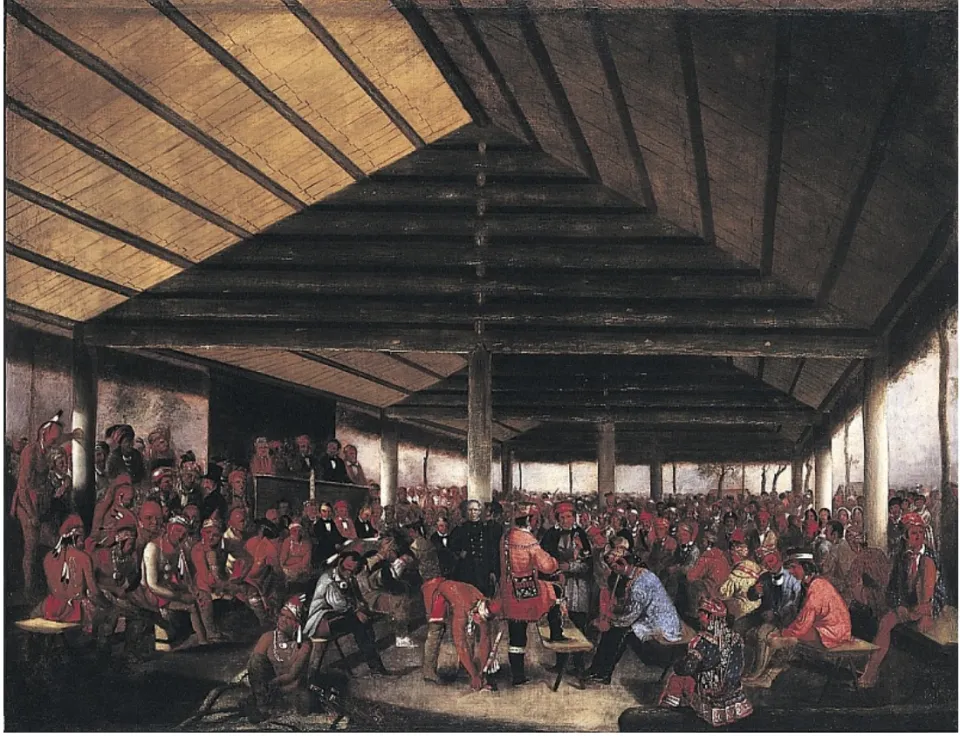

White settlers in the United States in the early nineteenth century coveted the land held by Native Americans. The U.S. government initially sought to limit the resulting conflict by treating Native American tribes as sovereign nations and negotiating treaties that established the boundaries of their lands. The U.S. government generally did little, however, to force settlers to respect the terms of treaties. Instead, Washington frequently imposed new treaties on Native Americans with even less favorable terms. With tensions between the two communities increasing, enthusiasm grew in the United States for expelling Native Americans from their ancestral lands. In 1830, Congress passed, at President Andrew Jackson’s request, the Indian Removal Act. Over the next two decades, the U.S. government repudiated its solemn treaty obligations and forced as many as one hundred thousand Native Americans living east of the Mississippi to relocate to smaller lands west of the Mississippi. SHAFR historians ranked the Indian Removal Act as the third-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Amy Sayward

Professor of History, Middle Tennessee State UniversityJames Stocker

Associate Professor of Global Affairs, Trinity Washington UniversitySyrus Jin

Elihu Rose Scholar in Modern Military History, New York University