Introduction

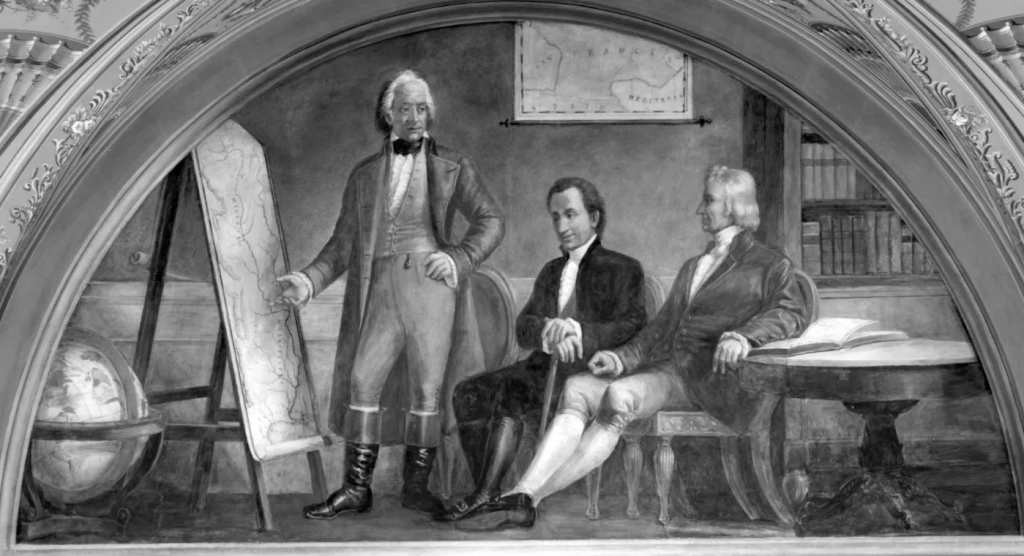

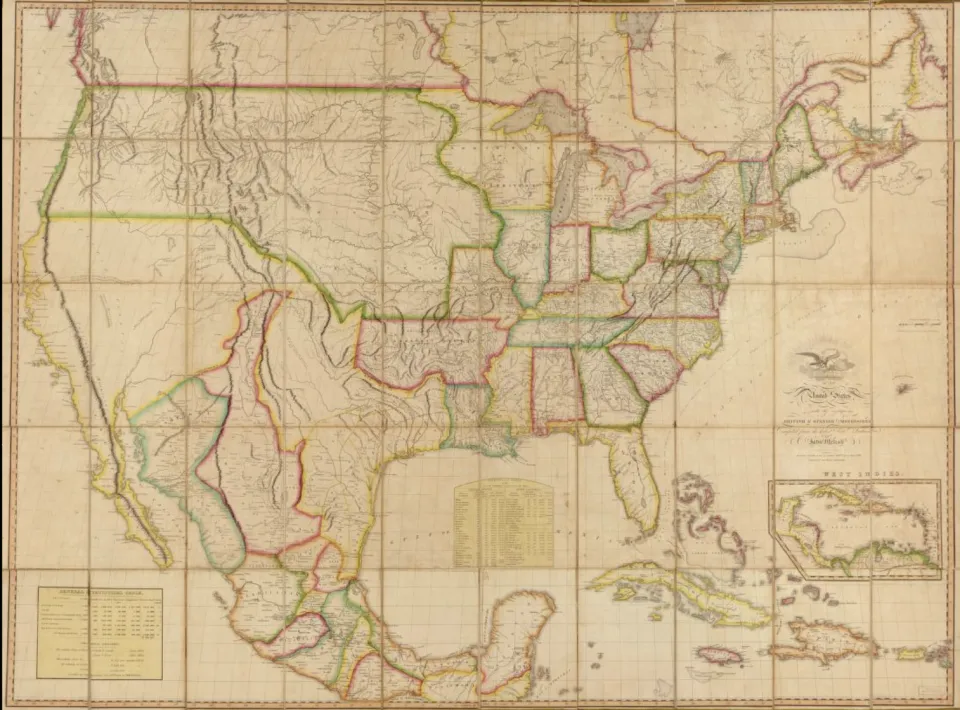

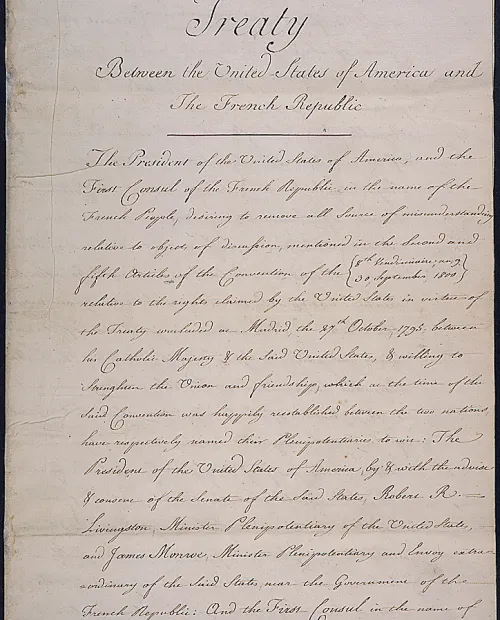

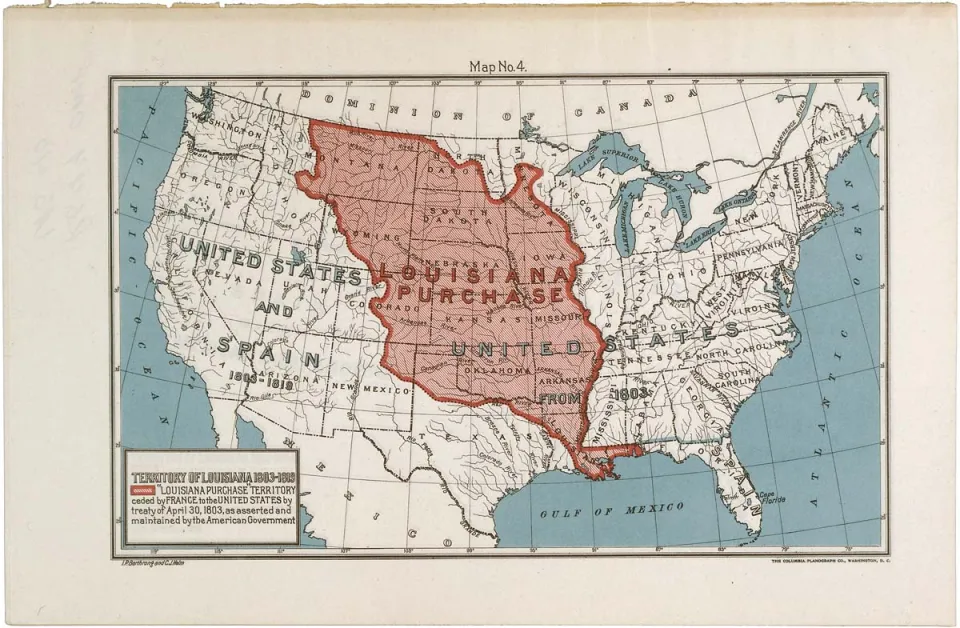

The United States emerged from the Revolutionary War with its independence, but the young nation remained vulnerable to foreign powers. Both France and Spain claimed territory west of the original thirteen states. Much of the trade of what was then the western United States flowed down the Mississippi River. First Spain and then France controlled the port of New Orleans, posing the threat that either could cripple the U.S. economy by cutting off access to the sea. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sent envoys to Paris with instructions to pay up to $10 million to acquire New Orleans and as much of the territory east of the city as possible. However, French leader Napoleon Bonaparte made the Americans a surprise offer: he would sell the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million. Jefferson worried that nothing in the Constitution authorized such an acquisition. However, he swallowed his objections and jumped at the deal. The purchase more than doubled the size of the United States, secured control of the Mississippi River, and put the country on the path to becoming a continental power. SHAFR historians ranked the Louisiana Purchase as the fourth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Joseph Parrott

Assistant Professor of History, Ohio State UniversityMichael Hopkins

Reader in American Foreign Policy, University of LiverpoolMichael J. Devine

Adjunct Professor of History, University of WyomingPhyllis Soybel

Associate Professor of History, Lake Country College