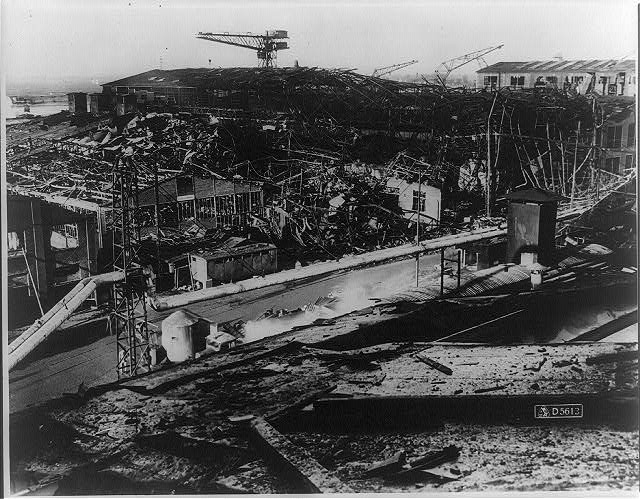

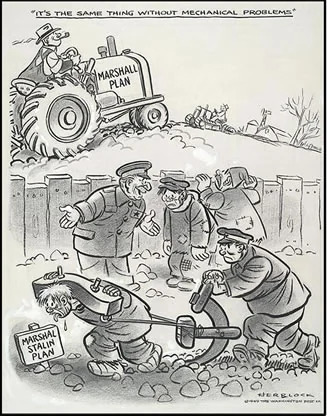

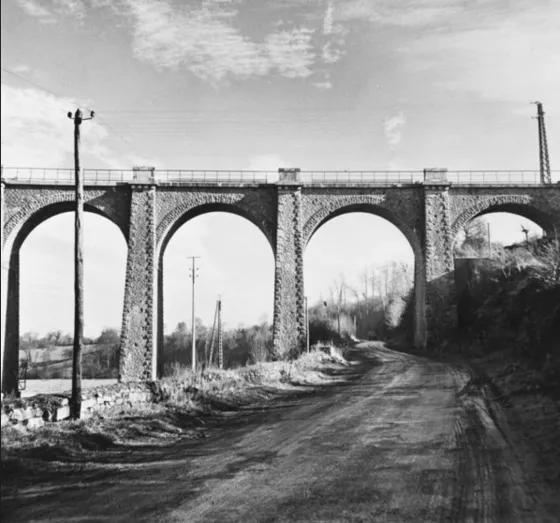

The United States allocated $13.2 billion (equivalent to roughly $180 billion in 2025 dollars) in grants and loans to sixteen European countries, including France, Italy, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and West Germany, over the next four years. As Marshall envisioned, European countries generated their own recovery plans and cooperated to allocate resources. Much of the aid went to rebuild railroads, highways, bridges, and factories destroyed during the war. Other aid provided food, oil, coal, and industrial machinery. But the Marshall Plan also funded activities ranging from medicine for tuberculosis, equipment for Portugal’s cod-fishing fleet, and sending Europeans to the United States to study advanced industrial and farming techniques.

The Marshall Plan’s impact was dramatic. By 1952, every recipient country had seen its gross domestic product (GDP) surpass pre-war levels, food shortages ended, and the quality of life improved. That turnaround cannot be attributed solely to the Marshall Plan. While the amount of U.S. aid was large in absolute terms, it was small relative to the overall size of European economies. But it inspired confidence in the future and spurred other public and private investment. The Marshall Plan also encouraged European economic integration, enabling each country to grow faster than it would have in isolation. In particular, the plan helped establish the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, which evolved into what we know today as the European Union. The creation of NATO, which was established one year and one day after Congress passed the Marshall Plan, also helped spur economic recovery by providing Europe with a vital security reassurance.

Western Europe’s economic growth in turn shored up its fragile democracies. Falling unemployment, rising wages, and improved living standards diminished the appeal of the radical proposals that Communist parties offered and left less room for the Soviet Union to meddle. Center-left and center-right parties flourished. Europe’s political crisis passed.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Ian Van Dyke

Visiting Assistant Professor, Grand Valley State UniversityMax Paul Friedman

Professor of History and Professor of International Relations, American UniversityAlexandra Penler

Oman Desk Officer, U.S. Department of StateLauren Turek

Associate Professor of History, Trinity University