Introduction

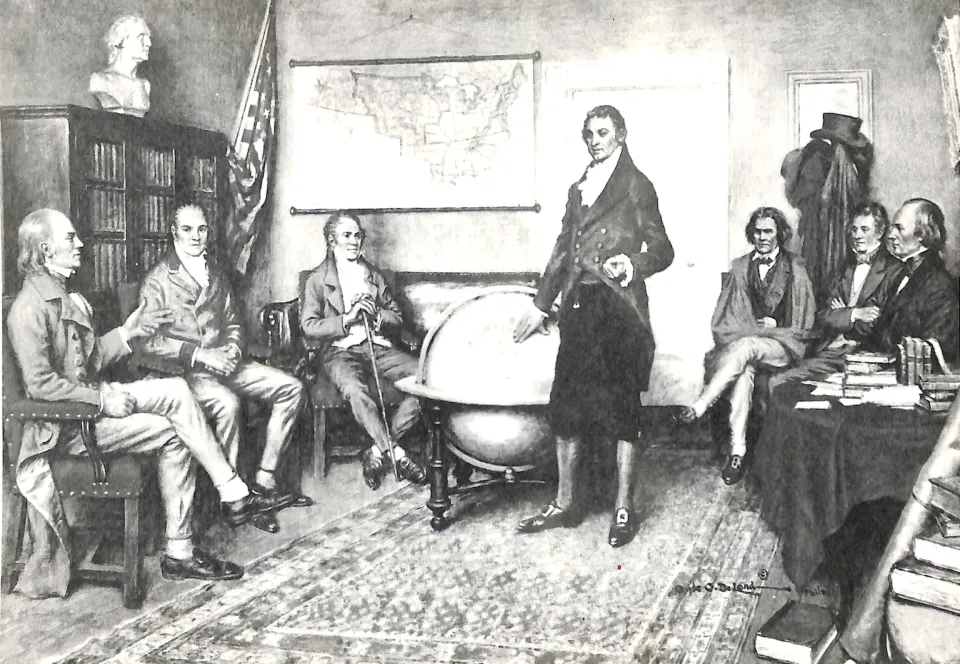

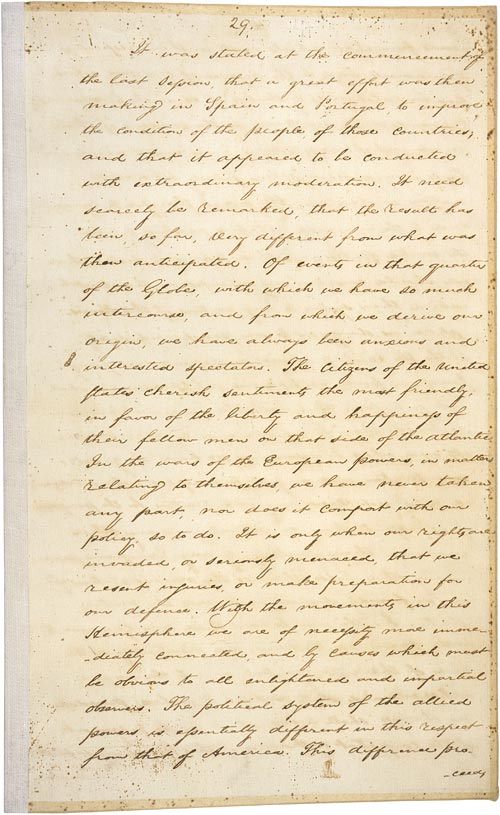

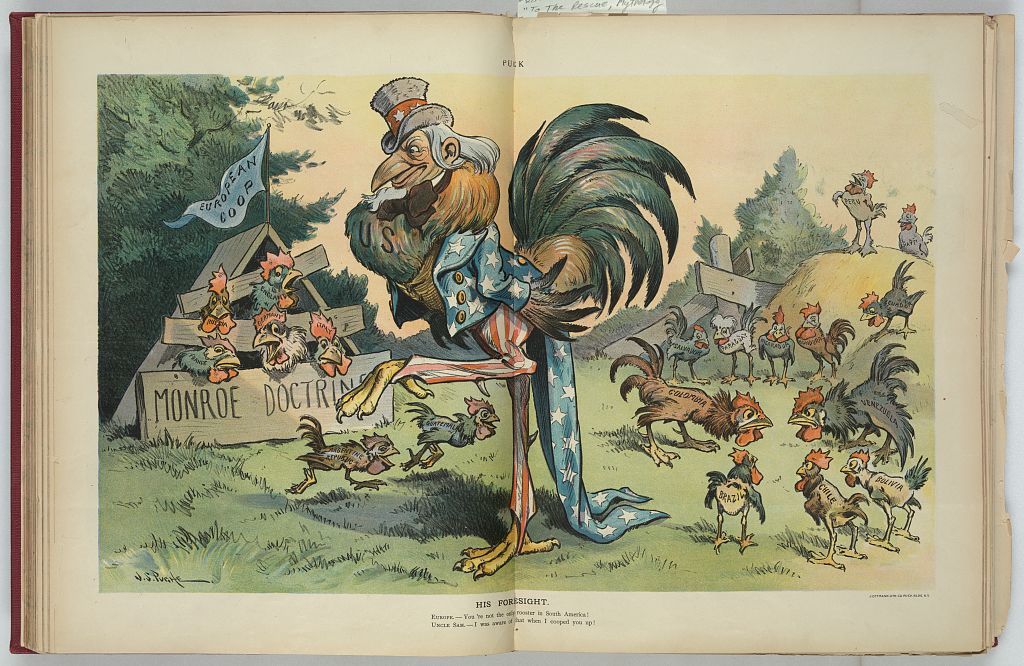

On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe delivered in writing his seventh annual address to Congress—the equivalent of today’s State of the Union address. In the middle of an otherwise forgettable summary of national issues, Monroe presented what would become a classic statement of U.S. foreign policy—the Monroe Doctrine. Monroe asserted that the Western Hemisphere was off limits to further European colonization and claimed the right for the United States to protect the sovereignty of the independent republics in the Western Hemisphere. Both claims were bold statements that the country had no way of backing up. But these bluffs were based on a shrewd diplomatic analysis that signaled to the world the far-reaching ambitions of the young country. SHAFR historians ranked the Monroe Doctrine as the ninth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Jared Pack

Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of History, York UniversityAdam Stone

Associate Professor of Political Science Emeritus, Perimeter College at Georgia State UniversityEmily Conroy-Krutz

Professor of History, Michigan State UniversityJoseph Stieb

Assistant Professor of History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hil