Introduction

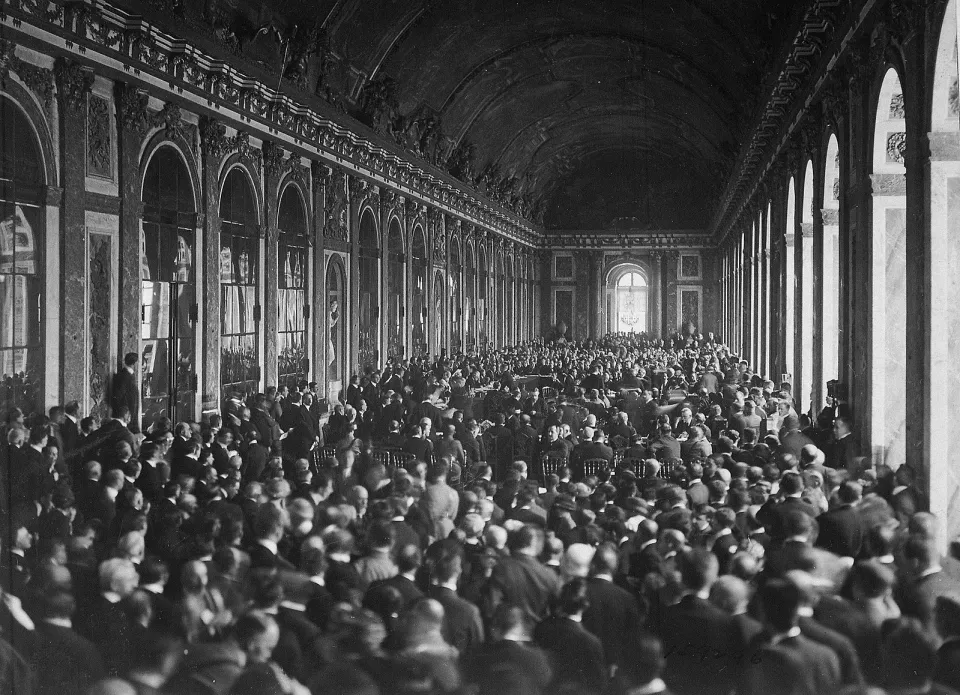

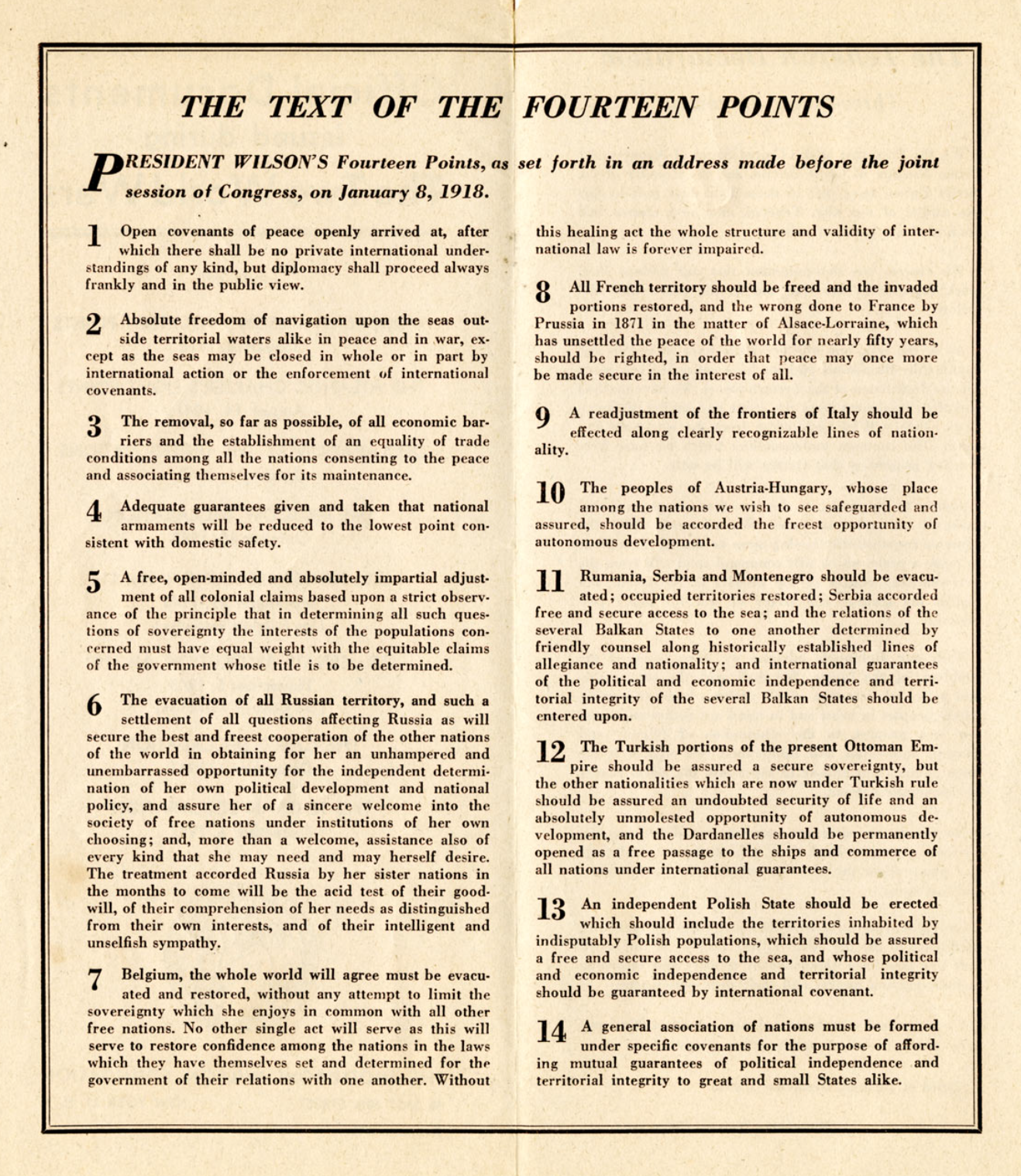

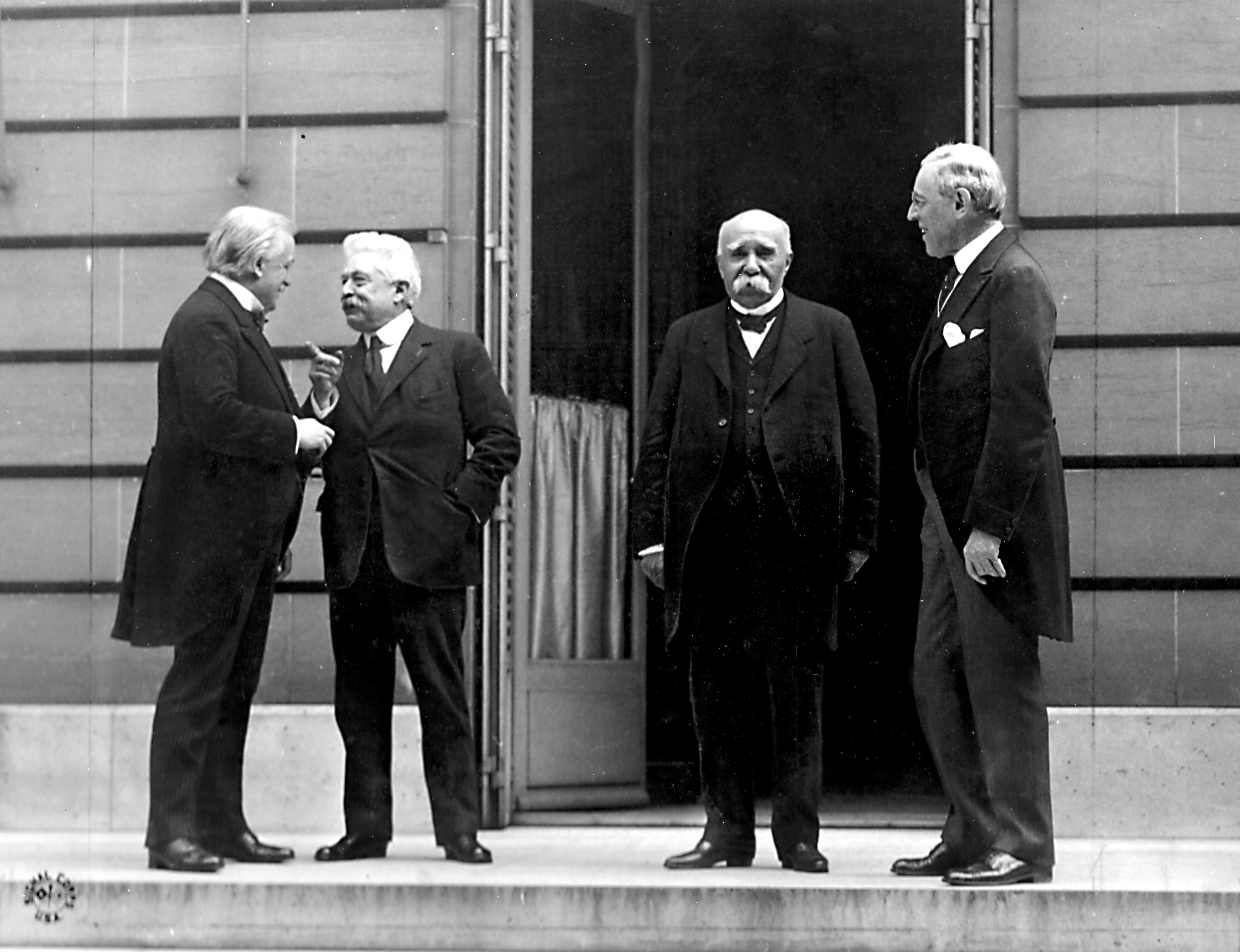

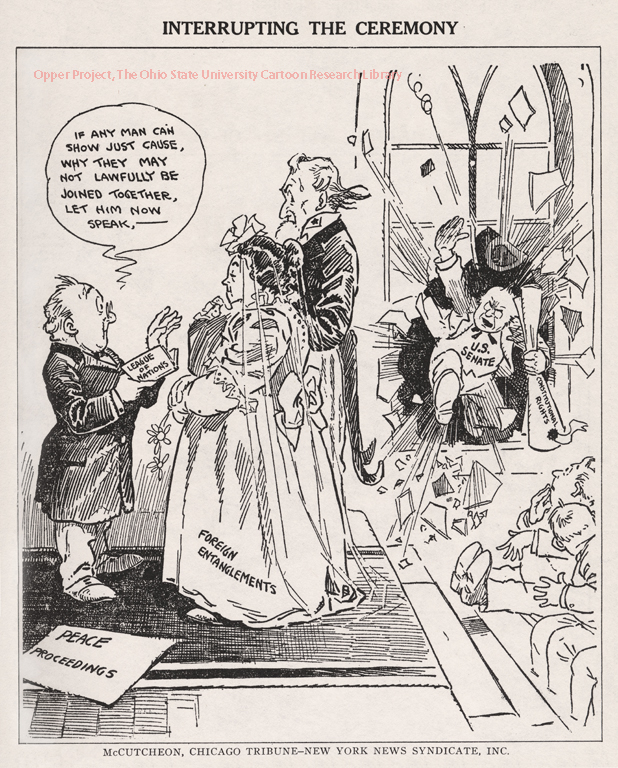

The U.S. entry into World War I broke with the United States’ longstanding practice of keeping out of Europe’s political affairs. President Woodrow Wilson saw that shift as an opportunity to try to restructure world politics to make future conflict less likely. He went to Paris in December 1918 to negotiate the war’s end. There he negotiated the Treaty of Versailles, which embraced his vision to create a League of Nations that would work to preserve peace. Wilson did not have similar success, however, at home. In November 1919 and again in March 1920, the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and with it, the League of Nations. The league began operating in 1920, but the absence of the United States handicapped its work. Declining to join the league also made it easier for the United States to ignore growing world crises over the next two decades, a decision it would come to regret. SHAFR historians ranked the Senate rejection of the Treaty of Versailles as the fifth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Andrew Pace

Professor of History, University of Southern MississippiCharles Laubach

Professor of History, The Ohio State UniversityNick Sarantakes

Professor, U.S. Naval War CollegeDavid C. Atkinson

Associate Professor of History and Social Studies and Director of the History Honors Program, Purdue UniversityJared Pack

Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of History, York University