Introduction

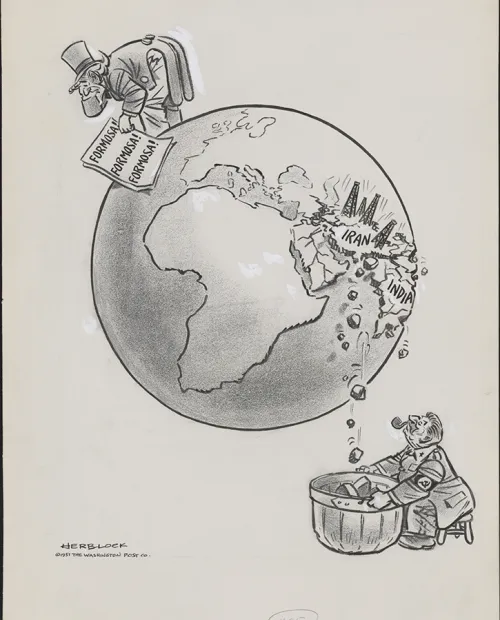

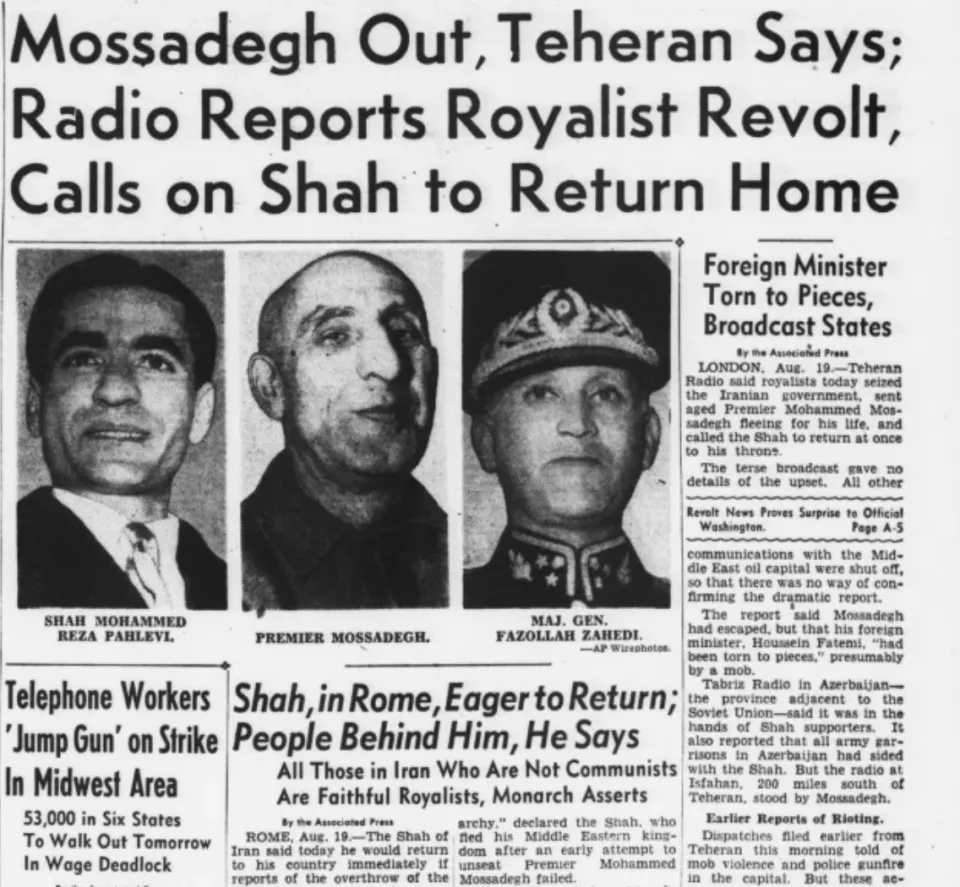

Mohammad Mosaddeq became prime minister of Iran in April 1951. An ardent nationalist, he rose to power by challenging Great Britain’s dominance of Iran’s economy and politics. A month before becoming prime minister, Mosaddeq led the effort by the Iranian Majlis (parliament) to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), which the British government controlled. Rather than seek compromise with Tehran, London sought to reverse the law by crippling Iran’s oil exports, the main source of government revenue. President Harry S. Truman rejected British efforts to enlist the United States in pressuring Iran to return ownership of AIOC to Britain. British arguments that Mosaddeq was destabilizing Iran found a more friendly audience when Dwight D. Eisenhower became president. Fearing that a communist takeover of Iran was increasingly likely, Eisenhower authorized Operation Ajax to oust Mosaddeq. The coup came in August 1953. Its success encouraged subsequent U.S. efforts to destabilize governments Washington disliked, and Iranian nationalists used the coup to fuel anti-Americanism in Iran. SHAFR historians ranked the support for Mosaddeq’s overthrow as fourth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Charles Laubach

Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History, The Ohio State UniversityJames MacHaffie

Independent Consulting AnalystSyrus Jin

Elihu Rose Scholar in Modern Military History, New York UniversityToshihiro Higuchi

Associate Professor of History, Georgetown University