Introduction

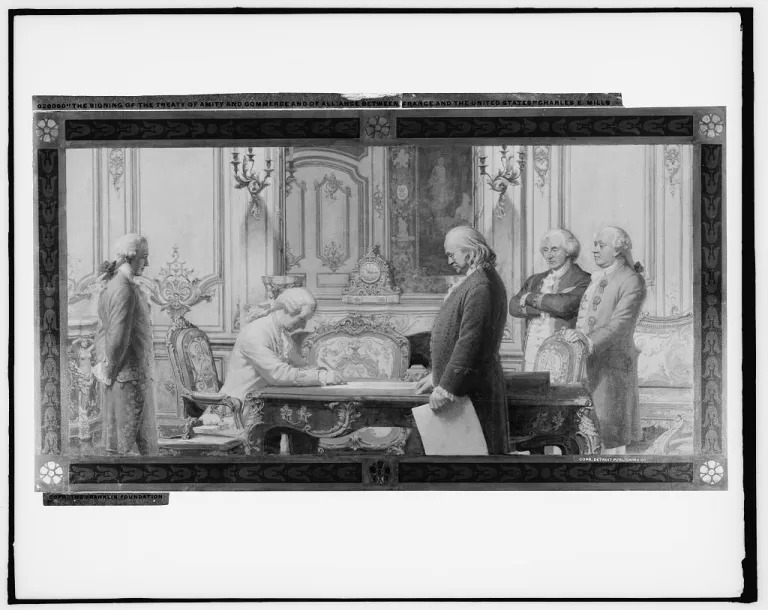

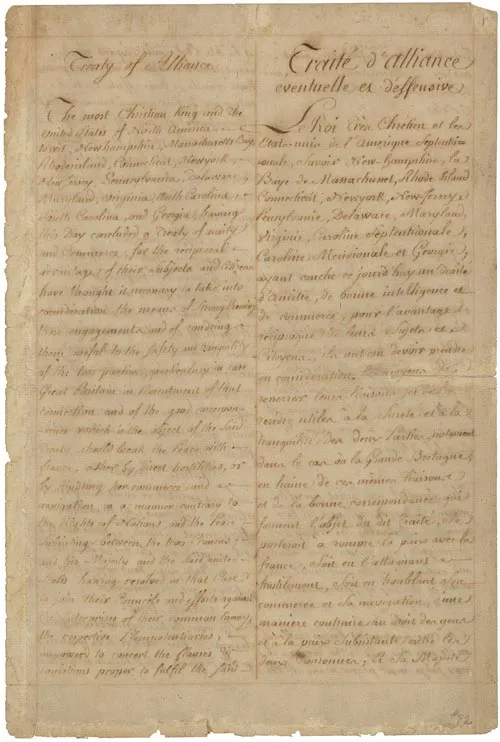

When the thirteen colonies declared independence in 1776, they turned to Great Britain’s rival France for aid. At first, France provided only clandestine support. It feared that publicly siding with rebels who were likely to lose would risk a war with Great Britain that had few benefits. But adept U.S. diplomacy and a critical American battlefield victory changed that calculation. On February 6, 1778, France recognized the independence of the thirteen American colonies and pledged to support their war with Great Britain. The agreement, which was codified in two separate treaties, was a turning point in the American Revolutionary War. France subsequently provided the colonies not only with military supplies and financial support, but also with land and naval forces. France’s entry into the war also forced Great Britain to divide its forces to guard against threats to its interests in Europe and the Caribbean as well as in the thirteen colonies. A war that the colonists seemed destined to lose became a war that they won—and that changed the course of history. SHAFR historians ranked the Treaty of Alliance with France as the third-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Robert Shaffer

Emeritus Professor of History, Shippensburg UniversityEmily Conroy-Krutz

Professor of History, Michigan State University