Introduction

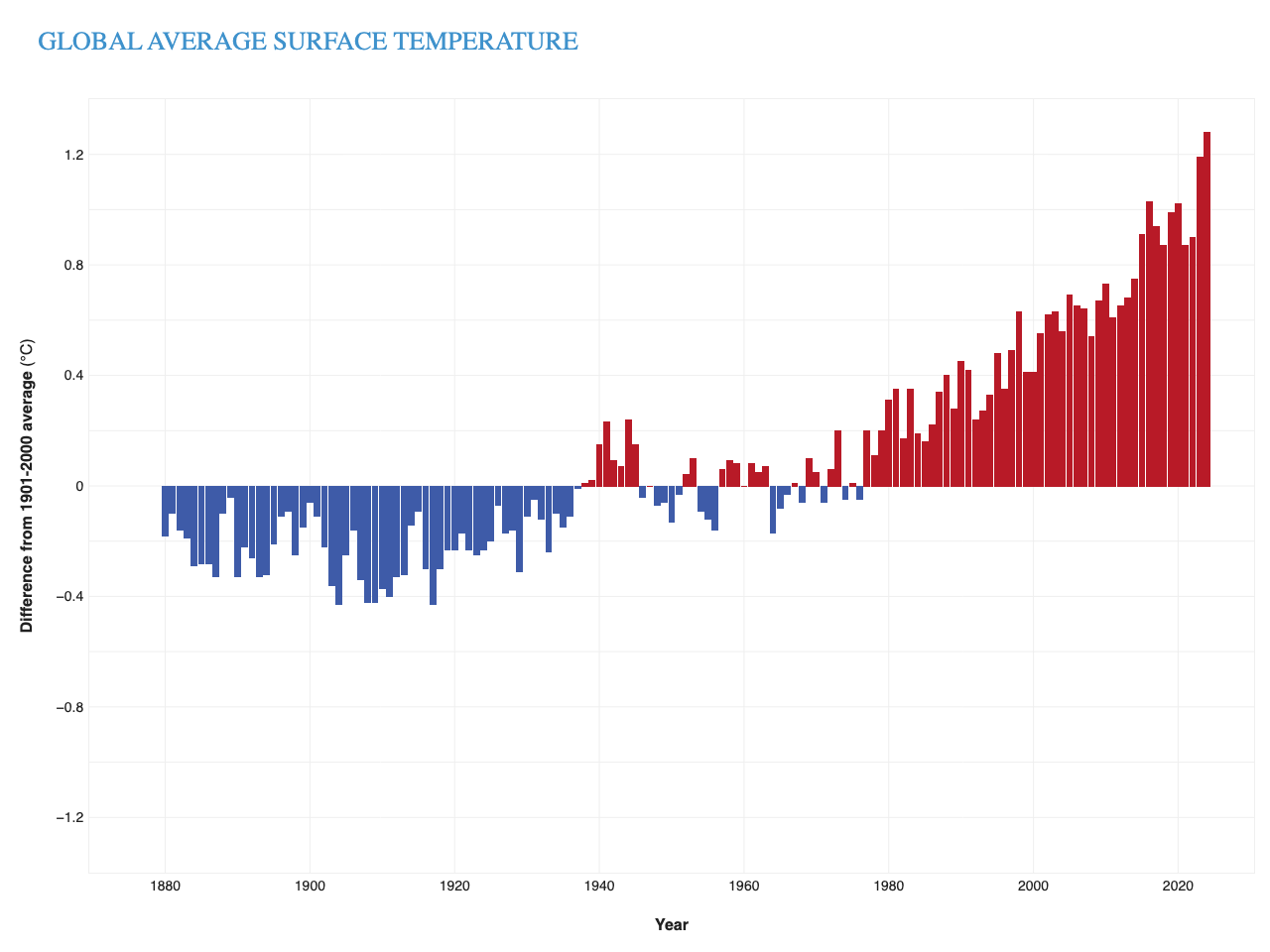

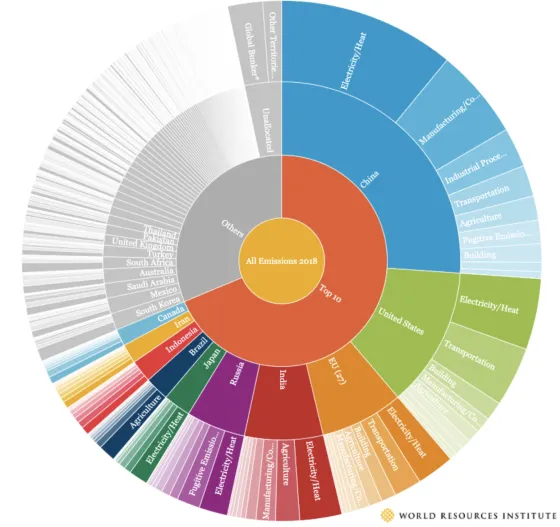

The signing of the Paris Agreement in December 2015 marked a breakthrough in climate diplomacy. After numerous prior failed attempts, 194 countries agreed to work to reduce the emission of heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide and methane that are changing the climate. The United States, the world’s second largest emitter annually and the largest emitter cumulatively, was among the countries that signed the Paris Agreement, which is also known as the Paris climate accord. On June 1, 2017, President Donald Trump, who had come to office five months earlier, fulfilled a campaign promise by announcing that the United States would withdraw from the Paris Agreement. He argued that the agreement would hamstring the U.S. energy industry and cost millions of American jobs while doing little to limit climate change, something he had repeatedly called a “hoax.” No other country followed Trump’s lead, leaving the United States diplomatically isolated as average global temperatures climbed and extreme weather events multiplied. SHAFR historians ranked the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement as the seventh-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

A list of featured comments

What Historians Say

Colleen Woods

Professor of History, University of MarylandEvan Bonney

Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History, Sciences Politiques ParisChris Nitschke

Research Fellow at the Rothemere American Institute, University of OxfordJustin Jackson

Associate Professor, Bard College