The Future of Global Health Is Urban Health

Health and infectious diseases have shaped the history of urbanization, but it is cities that will define the future of global health.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Thomas J. BollykyBloomberg Chair in Global Health; Senior Fellow for International Economics, Law, and Development; and Director of the Global Health Program

By Thomas J. BollykyBloomberg Chair in Global Health; Senior Fellow for International Economics, Law, and Development; and Director of the Global Health Program

“Cities were once the most helpless and devastated victims of disease, but they became great disease conquerors.” —Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Urban history passed a landmark in 2017. For the first time, more than half the people in low- and middle-income countries live in cities. But as urbanization continues to accelerate, particularly in poorer nations, the world will need to work to make those cities livable and healthful for their inhabitants.

For most of history, large cities were either wealthy industrial centers, like Liverpool or London, or the capitals of empires, such as ancient Rome, which could draw enough migrants from the countryside to compensate for the loss of city dwellers due to the unrelenting assault of infectious diseases.

Great epidemics like the Plague of Athens are famous for ravaging the urban centers of antiquity, but it was the everyday killers—tuberculosis, dysentery, and other intestinal and diarrheal diseases—that kept large cities deadly for millennia. Between the first and fifth centuries CE, the lives of residents of Rome were about 25 percent shorter than those of their rural counterparts. According to the anthropologist Mark Nathan Cohen, the urban populations of Europe in the fourteenth through the eighteenth centuries may have been the most “disease-ridden and the shortest-lived populations in human history.” As late as 1900, life expectancy in the United States was ten years greater in rural areas than it was in cities.

A combination of public health reforms, laws against overcrowded tenements, and better sanitation improved urban health in industrialized nations during the nineteenth century. In 1857, no U.S. city had a sanitary sewer system; by 1900, 80 percent of Americans living in cities were served by one. The percentage of urban U.S. households supplied with filtered water grew from 0.3 percent in 1880 to 93 percent in 1940. Improved access to filtered and chlorinated water could have accounted for nearly half of the decline in mortality in U.S. cities between 1900 and 1936.

With improved health and sanitation, fewer of the people who moved to urban areas for economic rewards died and the population of those cities expanded and prospered. In 1854, less than a tenth of the world’s population lived in towns and cities of more than twenty thousand residents. By 1920, the share of the world’s population living in cities grew to 14 percent, with nearly two-thirds of those urban residents residing in Europe and North America. That situation remained largely the same all the way through 1950, when only Kolkata and Shanghai breached the bottom half of top ten cities globally.

After 1960, urbanization began to shift to progressively poorer nations (see below). A comparison of the wealth of nations when they became more than one-third (33 percent) urbanized—a threshold that most countries now surpass—illustrates this trend. In 1960, no country with a per capita income below $1,250 was more than one-third urbanized. Only six nations with per capita incomes under $2,500 reached that threshold, all in Latin America. By 2016, though, in fifty-seven of the poorest countries more than one-third of the population lived in cities, many of those in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

This recent shift in urbanization to poorer nations is possible because of the declining infectious disease deaths in those countries. For most of human history, the only large cities were capitals of far-flung empires (such as ancient Rome) or industrial centers (such as nineteenth-century Manchester). They offered sufficiently high wages to induce enough people to move from farm to town to compensate for all the urban residents dying from infectious diseases. Today, the order by which urbanization is occurring has been reversed in many poorer cities (see below), with urban population growth occurring before the city has a strong economic base. Much of the population growth that has produced large poor world cities is natural; cities like Cairo, Delhi, Karachi, and Lagos have grown chiefly because their residents are living longer and fewer of their children are dying rather than because people migrate to those cities for jobs.

But even with migration, large cities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries grew slowly in population by today’s standards. That rate only began to quicken when cities invested in urban infrastructure—such as sanitation, clean water systems, and policies outlawing crowded tenements and poor factory conditions—that could help overcome the burden of respiratory and waterborne diseases. Prior to World War II, few effective medicines against infectious diseases existed. Antibiotics were not publicly available and most vaccines had not yet been developed. Cities expanded more slowly because migration to those urban areas was offset by short lifespans and high rates of child mortality.

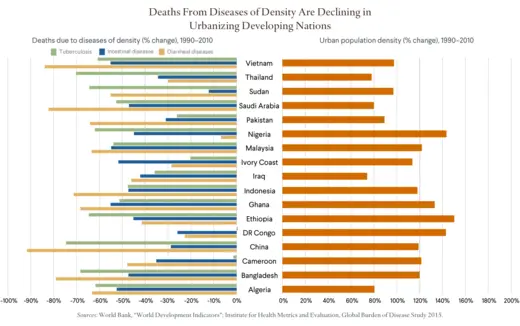

Today the decline in deaths from the traditional diseases of density—tuberculosis and diarrheal and intestinal infectious diseases—in many large cities is due less to prevention through infrastructure improvements and public health oversight (see below). Instead the evidence suggests that treatment (e.g., antibiotics, childhood vaccines, oral rehydration solutions), rather than prevention (e.g., clean water, sanitation, and strong urban public health systems), has mattered the most. For example, deaths from cholera and other diarrheal illnesses in lower-income countries are decreasing much faster than the incidence of these diseases.

Driven by naturally increasing populations, many cities in low- and middle-income nations are expanding at record rates. Between 1950 and 2010, the urban populations of Africa and Asia expanded as much as those in Europe did between 1800 and 1910, in half the time.

Indeed, population growth is outpacing city infrastructure in the fastest-urbanizing nations, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. The availability of piped water in cities in the region fell by 10 percent between 1990 and 2015, and only four out of ten new city residents had access to improved sanitation as defined by the World Health Organization [PDF]. The construction of adequate housing and paved roads is likewise not keeping up with urbanization in many poor cities.

One worrisome consequence of population growth outstripping urban infrastructure has been the expansion of slums, overcrowded areas with inadequate housing and public services. The United Nations estimates that 881 million people lived in slums in lower-income nations in 2014, roughly one out of every eight people worldwide. In Africa and South Asia, a majority of city residents live in slums. Almost the entire urban population (96 percent) of the Central African Republic lives in similar circumstances. By 2030, the population of slum dwellers is expected to reach two billion globally.

Evidence is mixed on whether cities can continue to conquer disease as poor nations rapidly urbanize. The slums in lower-income nations today are considerably healthier than were the nineteenth-century cities of the United States and Europe, where between two hundred and three hundred out of every one thousand children under five died. There is limited health data on modern slums, however, and much progress is reported in averages that may mask disparities. There is some indication that the health benefits of urban life may not equally distributed to the poor residents of cities like Cairo, Dhaka, or Nairobi.

There are also significant challenges ahead. Poor, crowded cities with limited health systems are ideal incubators for outbreaks of emerging infections, like the Ebola epidemics in West Africa in 2014 and the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2018. These cities are often larger and denser than Athens and the other urban centers of antiquity, which means diseases are more likely to spread and more likely to affect a larger number of people. Outbreaks that occur in today’s cities can spread internationally faster and more easily, with the increased speed and volume of global trade and travel.

Pollution is also a threat. Air pollution is the fourth-leading health risk globally, responsible for killing an estimated 6.1 million people prematurely in 2016. Sixteen of the world’s twenty most polluted cities are in South Asia.

Many of the cities most exposed to coastal flooding from climate change and suffering water shortages—both of which carry health consequences—are in poor and emerging economies. These cities are located along coasts or in river deltas, which had been beneficial for farming and commerce, but now exacerbate the risks of flooding—and therefore of waterborne diseases—for large, poor, and informally housed populations. Many of these cities are also running dry. For example, roughly 90 percent of the Dhaka’s water supplies comes from ground reserves that are being fast depleted by the demands of its sixteen million inhabitants.

There is no quick or ready-made fix for creating sustainable urban infrastructure in sprawling, already-built poor world cities, but instituting the right incentives can help. Many residents of developing-country cities, especially those living in slums, lack clear property titles to their homes. Establishing easily enforceable land rights can promote investment in formal housing, free workers to move to find jobs and get access to city services, and establish the foundation for a property tax system. With the resulting resources and a bit of empowerment from national governments, city governments may be freer to do more to improve their business environments, ease bureaucratic constraints on small- and medium-sized enterprises, and attract private infrastructure investment. Municipal governments may also prove more capable than national authorities in responding to the demographic pressures and the health and environmental challenges that poor cities face. A World Bank study of African cities providing the best water services to the poor found mayors behind several of the success stories, including those of Durban, South Africa, and Nyeri, Kenya.

Health has shaped the history of cities, but it is cities that will define the future of global health and economic development. The majority of the world’s population already lives in urban areas. The population of city dwellers globally is projected to grow by 2.5 billion by 2050, with nearly 90 percent in lower-income nations in Africa and Asia. Urbanization in lower-income nations could offer billions of people better access to jobs and health-care services, and a gateway to the world economy. To reap those benefits, those nations will have to confront the looming health and environmental challenges of urban life.

This interactive is one in a series of data interactives that CFR is producing on the changes occurring in global health and their broader implications for societies and economies. The first one, The Changing Demographics of Global Health, reveals that population growth and aging are fueling a dramatic rise in noncommunicable diseases in poor countries that lack the health-care systems and funds to handle them. The third, Democracy Matters in Global Health, shows that a country’s democratic experience is increasingly important in reducing noncommunicable diseases and injuries among adults. This interactive was made possible by a generous grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no affiliation with the U.S. government.