By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

By

- Benjamin Della RoccaAnalyst, Center for Geoeconomic Studies

China is renowned for hitting its government’s targets through state intervention, so the IMF’s pessimism may be justified even if the country does another bull’s eye on GDP. The data coming from China do, in fact, show the trade war having a worrying impact on economic activity.

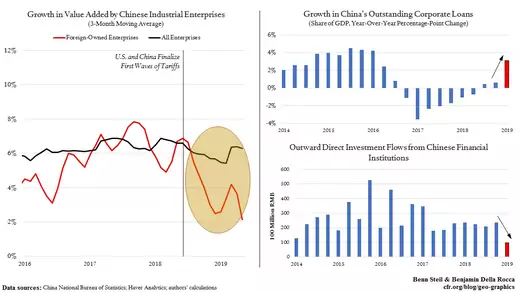

As shown in the left-hand graphic above, growth in the value added by foreign-owned firms in China has plunged since the trade war began one year ago, with trade fears pushing companies to shift production abroad. In consequence, private spending is contracting.

Beijing, however, is counteracting the fall through its favored tool—pushing more domestic borrowing, while restricting foreign lending. As the top right graphic shows, China’s outstanding corporate loans surged last quarter by over three percent of GDP—the largest jump since 2015. Meanwhile, as the bottom right graphic shows, outward foreign direct investment from Chinese financial institutions plunged by 59 percent—to its lowest level since 2013.

Given China’s massive debt levels—equivalent to 254 percent of GDP, among the highest in the world—and the fact that most new corporate lending has been going to the country’s least-profitable state-owned companies, the country is edging closer to debt crisis. How it manifests itself—mass defaults, recession, soaring inflation, extended stagnation—depends on which poison the government decides to drink when. But there can be no doubt that, for Beijing, the trade war is a “big deal.”