Why the Silicon Valley Model Failed Cleantech

It’s no secret that venture capital (VC) has fled from the clean energy technology (cleantech) sector, and as a result, new cleantech company formation has slowed. But why did this happen, and is there a future for cleantech?

To answer these questions, today I’m excited to release an MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI) paper entitled, “Venture Capital and Cleantech: The Wrong Model for Energy Innovation,” with my colleagues Ben Gaddy at the Clean Energy Trust and Frank O’Sullivan at MITEI.

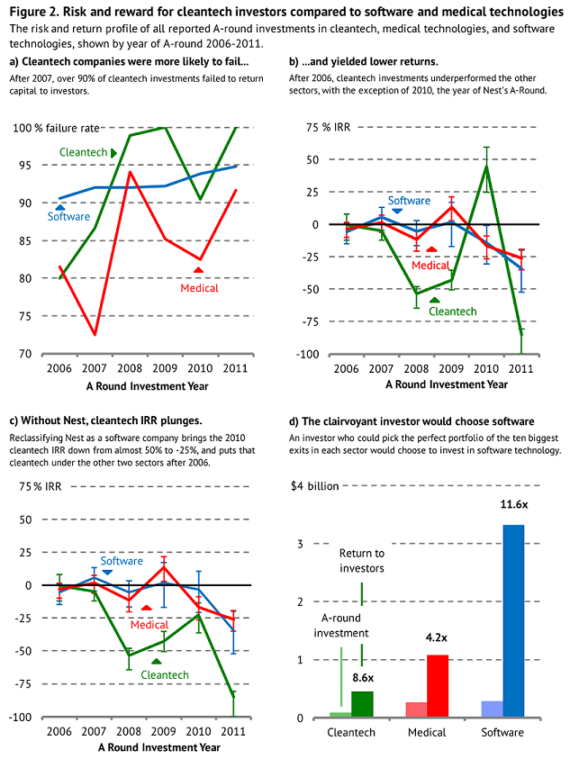

We compared the performance of every medical technology, software technology, and cleantech company that received its first round of VC funding between 2006 and 2011. We found that betting on cleantech start-ups just does did not make sense for VCs, because the sector could not deliver the outsized returns found in other sectors.

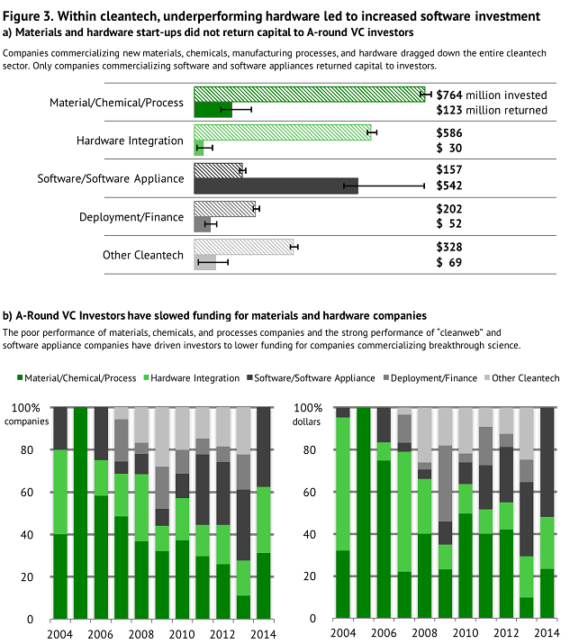

In particular, companies developing new solar panels, batteries, biofuels, other new energy materials and manufacturing processes collectively destroyed over 80 per cent of the initial capital investment by VCs. Many required large amounts of funding to build factories and their technologies took longer than five years to develop. The few that succeeded still did not deliver enough capital return for VCs to justify staying in the sector.

A Losing Combination: High Risk and Low Returns

Below, Figure 2 from our MITEI paper breaks down the underperformance of the cleantech sector:

Interestingly, the way we classify Nest Labs—which sells sleek thermostats that intelligently regulate indoor temperature to reduce power bills—heavily influences the results. If we count Nest as a software company, which is reasonable, overall cleantech sector performance plunges. This suggests heterogeneous company performance within the cleantech sector. Indeed, when we broke down cleantech into five subsectors, we found that clean software companies were profitable investments, whereas materials and hardware companies performed the worst (Figure 3).

Wanted: Corporate Partners

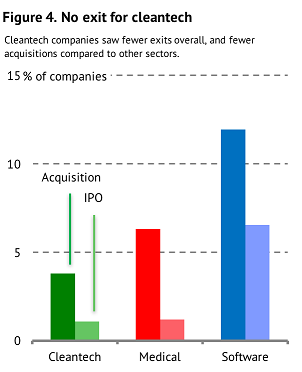

It makes sense that cleantech companies scaling up new materials or hardware might underperform software companies that required less up-front capital from investors and paid VCs back handsomely after only a few years. But some other factor is needed to explain why cleantech underperformed the biomedical sector, which can also be capital-intensive and has successfully scaled up lab bench innovations.

That factor is corporate support. Figure 4 from our paper demonstrates that biomedical start-ups were twice as likely to be acquired than cleantech start-ups, offering VCs lucrative returns on their investments. In contrast to biomedical corporations willing to strategically invest in innovative start-ups, energy companies—whether electric utilities or oil and gas firms—rarely invest in start-ups or even in-house research and development.

Just this weekend, I was reminded of the importance of corporate partnership when I sat down with a cleantech entrepreneur who isn’t following the Silicon Valley model. Bill Brown, CEO of NET Power, is commercializing an innovative power plant that runs on natural gas but produces pipeline-ready carbon dioxide for enhanced oil recovery, other industrial uses, or sequestration rather than spewing carbon emissions into the air. (Dave Roberts at Vox has an excellent write-up on the details). Brown is well on his way to building a 50 MW demonstration project in Texas thanks to support from corporate investors and partners. Exelon (a utility) and CB&I (an engineering firm) have made equity investments of $150 million, and Toshiba (a conglomerate with experience building turbines) has developed a special combustor and turbine in exchange for an exclusivity license with NET Power. Brown told me that working with corporate partners has brought engineering expertise, substantial capital, and the confidence to put steel in the ground.

Beyond Venture Capital

We close our paper by noting:

One lesson that entrepreneurs may take away from this story is that cleantech companies need to adapt to fit the constraints of VCs. Perhaps any cleantech company ought to be a software company in disguise, and new materials and processes are hopeless money losers.

That lesson is wrong and could be a disastrous impediment to the development of much-needed clean technologies to upend the world’s energy systems—a transformation that software alone cannot accomplish. The correct lesson is that cleantech clearly does not fit the risk, return, or time profiles of traditional venture capital investors. And as a result, the sector requires a more diverse set of actors and innovation models.

Those new actors include Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Coalition, which has pledged to provide billions of dollars in “patient capital” that could transcend the capital and time constraints of VC investors. Institutional investors and corporations will also be crucial to supporting the cleantech sector. To entice these new private actors, public policymakers must de-risk their investments, and we outline a suite of initiatives to do so. Indeed, we conclude, “the rise and fall of hundreds of start-ups might have an upside if a new generation of public and private support avoids the missteps of the cleantech VC boom and bust.”