After Shift from East to West, Maritime Piracy Remains Threat to U.S. Seafarers and Interests

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for John Campbell

This is a guest post by Michael Clyne. Michael is an assistant director at Drum Cussac, a global risk management consultancy.

When President Obama took office nearly eight years ago, his first national security test came within one-hundred days, not from al-Qaeda or the self-proclaimed Islamic State, but pirates. It was the rescue of Captain Richard Phillips, the merchant mariner kidnapped aboard U.S. container-ship Maersk Alabama off the Somali coast, which triggered the president’s first known standing order for lethal force. At the time, the Gulf of Aden, which separates the Middle East from East Africa, was the world’s piracy hotspot, spawned from the lawless destitution of lower Somalia.

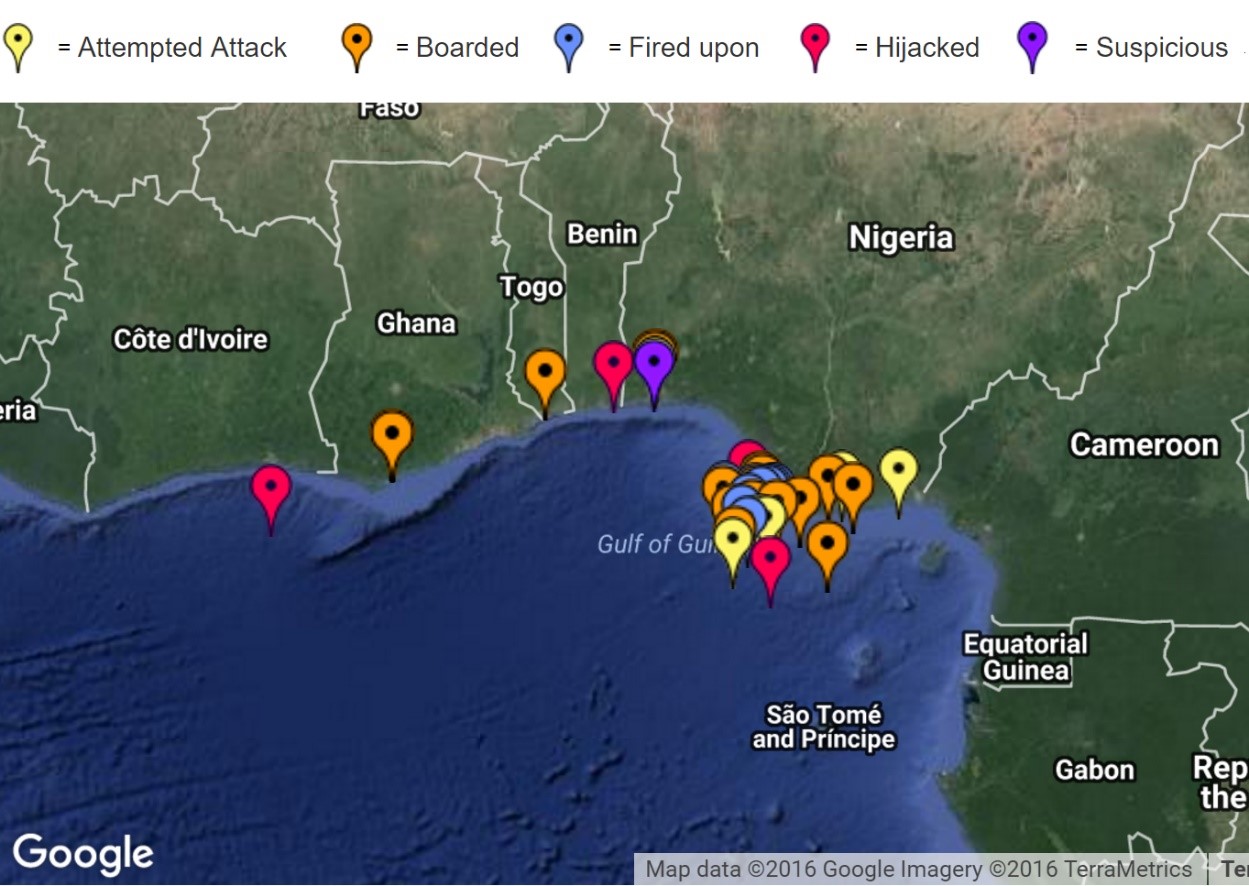

Flash forward a decade, and East Africa’s pirate problem has been largely tamed through a combination of multinational security and development measures. However, rather than receding, the threat has shifted westward to the Gulf of Guinea, where unsecured territorial waters fuse domestic militancy and international piracy. Today, West Africa’s maritime space is precarious, and worsening conditions there could precipitate a similar crisis as a new president takes office.

The un-policed Gulf of Guinea waters off West Africa, namely Nigeria, have long overtaken the Gulf of Aden in recorded piracy attacks, endangering American lives and commerce, yet lack the headline-grabbing infamy of Somalia. That could change as Nigerian security offensives increasingly drive criminal networks offshore, causing more brazen attacks that target crew members rather than their cargo or devalued oil. Pirate kidnappings during the first nine months of 2016 more than doubled annual rates for 2015 and 2014, according to IHS Maritime & Trade, driven largely by Gulf of Guinea piracy.

Unlike the Gulf of Aden where crew members became captives aboard their own vessels, most Gulf of Guinea hostages are transferred onshore, to the Niger Delta, a lawless maze of mangrove swamps where governments have little reach. Within the past three weeks, Nigerian pirates have attacked two product tankers, a supply vessel, hijacked a gunboat, and kidnapped three international crew members; last month, they also attacked a Maersk container-ship, the same line and type as the Phillips hijacking. This trend not only puts crew members in significant danger, but also subjects the shipping industry to high costs, including the dilemma of ransom negotiation.

Yet, West Africa’s web of territorial waters and regulations continue to hamper efforts to curtail piracy, precluding continuous military escorts or reliable trading routes as with the Gulf of Aden. In the constricted space that remains, multinational coordination represents the best opportunity to improve maritime security in and around Nigeria. Since his first meeting with President Obama in 2015, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari has requested U.S. cooperation in combatting piracy off West Africa, where this month he called for a regional response. It’s in U.S. interest to agree with Mr. Buhari and engage Gulf of Guinea nations in a multinational preventative strategy, rather than a series of bilateral ones or solely interdiction exercises. And since the causes of offshore insecurity are rooted onshore, preventative approaches should address corruption and the other structural West Africa problems which enable piracy. Until then, the specter of piracy might pivot or transform, but not disappear, and return to haunt another administration.